This is the first collaborative visual essay for Fashionably Late Takes. In keeping with our argument that art education should be interdisciplinary, this piece is written by a poet and a painter. Co-author

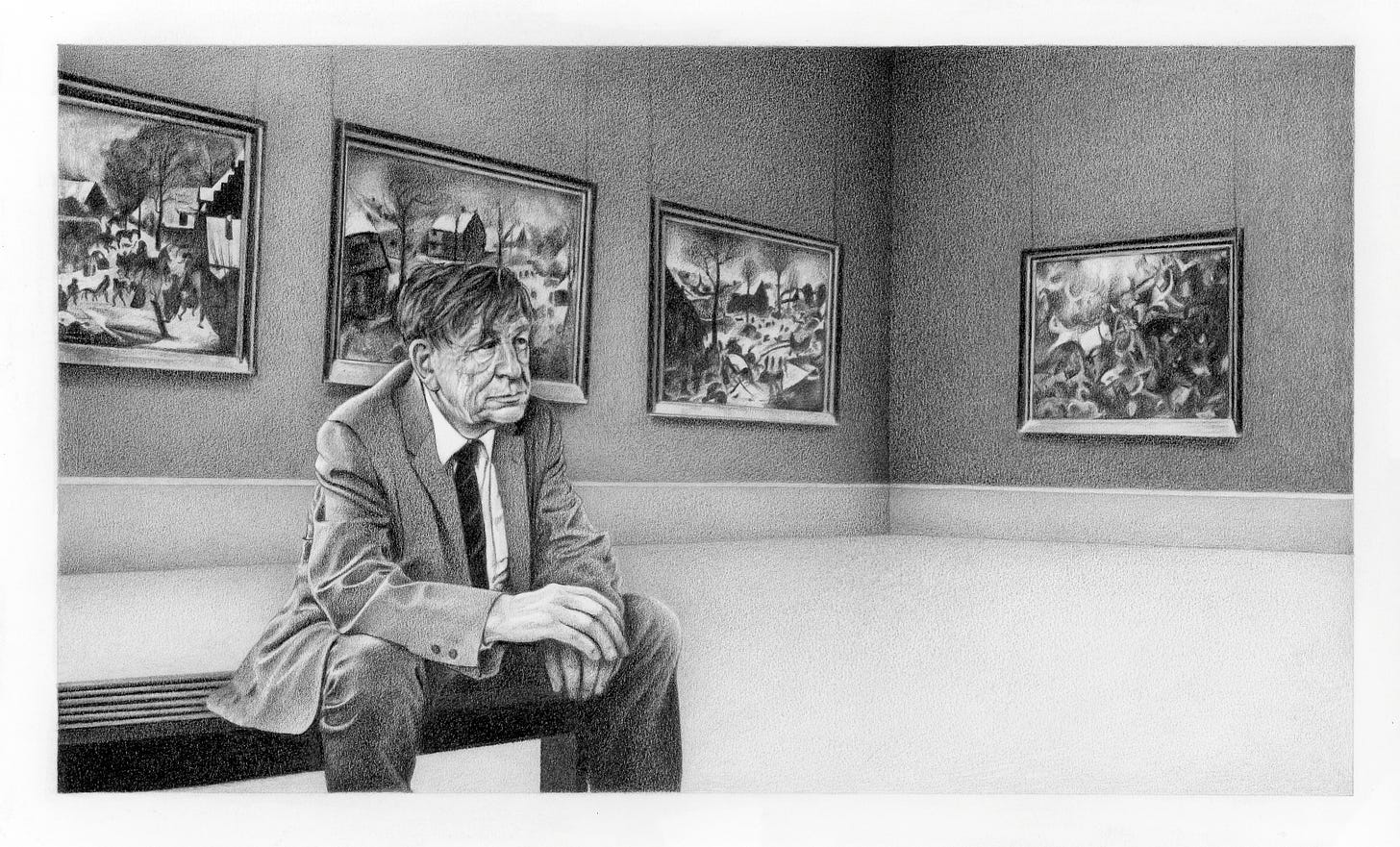

writes about literature on , which you should explore and subscribe to by following this link:No art form should be studied in isolation. To be fully understood, each one requires a robust comprehension of all other arts and humanities fields. Why, then, do we mandate literature courses in high schools but treat music, art, and philosophy as electives? Why can students of literature quote lines from William Shakespeare, yet not be able to identify work by the Renaissance artist Giulio Romano that The Bard references in The Winter’s Tale? Why do we teach entire college courses on W. H. Auden without expounding on paintings by Pieter Brueghel the Elder?

After viewing Brueghel’s Landscape with the Fall of Icarus in the Royal Museums of Fine Arts in Belgium, Auden wrote “Musée des Beaux Arts,” a poem that demonstrates Auden’s unique love of the visual arts. Brueghel, one of the most significant painters of the Dutch Golden Age known for his landscape scenes, creates a pastoral world and retells the Greek myth of Daedalus and his son Icarus. If you remember your Greek mythology, or if you’ve studied James Joyce’s Portrait of an Artist as a Young Man, then you’ll remember Daedalus as the creator of the labyrinth that held the half-bull, half-human Minotaur. In a sequel to the Minotaur myth, Daedalus reappears with his son Icarus in Ovid’s Metamorphoses — except now, they are the captives. The renowned inventor decides to build wings so that they can fly out of their prison.

Because the wings are made of bird feathers and beeswax, Daedalus warns Icarus not to fly too close to the sun that would melt the wax. Icarus, like any brash Greek hero, disobeys his father’s admonition and flies too high. As we are left to contemplate his hubris, Icarus plummets to the ground, his wings melting in the sunbeams, and drowns in the sea.

Auden’s poem alludes directly to Brueghel’s painting and uses ekphrasis — a poem that describes a work of art — to put painting to words and to create a vibrant scene. While Auden comments not on the myth itself but Brueghel’s interpretation of heroism in what is most likely a commentary on the unrest leading up to the Second World War, we can see the direct artistic influence on his work and notice the dialogue that Auden establishes with the artistic tradition. In his opening lines, he evokes “The Old Masters" of painting as his Muse:

About suffering they were never wrong,

The Old Masters: how well they understood

Its human position; how it takes place

While someone else is eating or opening a window or just walking dully along

Then Auden ends his poem by mentioning “Brueghel's Icarus" as an example of an Old Master conveying suffering well. Brueghel painted humanity going about mundane life with no concern for the boy's extraordinary flight and fall. (This is unlike how, in Ovid's telling, witnesses were enthralled — did Auden believe that Brueghel understood suffering better than Ovid?) If you look at the painting, Icarus's flailing feet might be the last thing you notice, because the composition is dominated by the routines of pastoral life.

In Auden’s “Musée des Beaux Arts,” we get a modernist poem referencing a Northern Renaissance painting that depicts ancient Greek oratory about a myth. Given these layers upon layers of history, you simply cannot understand Auden without learning about “The Old Masters" and Greek mythology. When you read “Musée des Beaux Arts,” Auden does not offer a visual aid, relying on you to summon Brueghel’s painting with your mind's eye (remember, he was writing before Google). Auden does not explain the myth of Icarus, because he reasonably expects that his readers should be cultured enough to recognize the reference. So if you ever took a college course on Auden that failed to expound on Brueghel — or Ovid — then you were cheated out of a genuine liberal arts education.

Students of the fine arts are similarly shortchanged. If you pursue a degree in painting and drawing, then you may only encounter Brueghel briefly in a survey course. Most studio art students are not required to learn enough about art history, and when they are, the focus is largely on the last century of Modern and Postmodern art. For many a budding painter, most of their required art history lessons are crammed into a couple classes, and further learning about older historical eras come from elective courses that they may not opt to take. Their first survey likely includes everything between the Chauvet cave paintings of the Paleolithic era to Medieval European altarpieces in a single course; the second survey class usually begins with the Renaissance and speeds through to our contemporary times.

Survey courses are an excellent initiation to the overarching thrust of art history, but painters should know more than an introduction to their own tradition. Because the art world that painting students graduate into is preoccupied with art from the past century, art schools undoubtedly need to impart knowledge that will help their students impress future colleagues. When aspiring artists mingle at gallery openings, they must deftly demonstrate awareness of contemporary art; few care if they remember Brueghel — much less whether they know that Auden admired him — but it is a faux pas to draw a blank when someone mentions living giants of contemporary art like Kara Walker.

Just as the literature student spends more time reading “theory" about literature than actually reading Homer or Dostoyevsky in full, painting students focus on learning about current popular artists at the expense of developing a strong art historical background. Given this limited focus on sampling mere excerpts from their own fields, insisting that literature and art students also study every aspect of the humanities is an ambitious demand. But this is a recent problem.1

The idea of a holistic approach to the humanities can be traced to the original concept of the “liberal arts education” — a type of education concerned with well-rounded humanistic inquiry — from the Ancient Greeks, who conceived an education system called paideia that aimed to prepare students for a rewarding life as citizens in poleis, or city states. Aristotle discusses the concept of paideia at length in Book VIII of his Politics (his response to Plato’s Republic that features a more measured take on the ideal city-state) and identifies reading and writing, music, drawing, and gymnastics as the core subjects that comprises what we call a “liberal” education.2 In Latin, the word paideia — which means “upbringing” or “education of a child” — was translated as humanitas, a word that means both “human nature” and “refinement, culture, and civilization.” For the Romans, therefore, who borrowed the Greek concept of the liberal arts education, the idea of human nature was intimately intertwined with the idea of culture and civilization. To be a good citizen — and, indeed, a fuller human being — was to be not just educated but also cultured.

The Ancient Greeks had nine Muses — goddesses of artistic endeavors that were said to inspire poets, dramatists, dancers, and any other sort of creative soul looking to make their mark on the world. Each Muse was responsible for a different sort of art form — Erato represented lyrical poetry, Clio represented history, Terpsichore represented dance — yet despite the Muses’ division of labor, for the Greeks, poetry was not separate from music, history was not distinct from art. Indeed, the Muse of music, Euterpe, was also the Muse of elegiac poetry. For the Greeks, poetry was always accompanied by song, and there was virtually no distinction between a poem and a song. In fact, the second word of the opening line of Homer’s The Iliad is ἄειδε or “sing,” and the poem was not recited plainly but always accompanied by music. The Greek god Apollo was at once the god of dance and music. Greek tragedies invoked an onstage chorus, and satyr plays — the genre we might call “tragicomedy” today — often featured singing and dancing. In the world of the Greeks, a poem sang a song, and as the poet John Keats was destined to remind humanity thousands of years later, an urn told a story. A musician was a poet, and the arts were one.3

Perhaps the most famous example of the overlap of artistic “genres,” as we so rigidly think of them today, is the ekphrastic poem that describes a work of art, like Auden’s “Musée des Beaux Arts.” Greek poetry is replete with the style we call ekphrasis, and the most notable instance of this literary device occurs in Book 18 of Homer’s The Iliad in a description of Achilles’ shield. In the following excerpted lines from Alexander Pope’s wonderful translation of the Greek work, notice how the poem brings the artistry of Achilles’ shield to life:

Two cities radiant on the shield appear,

The image one of peace, and one of war.

Here sacred pomp and genial feast delight,

And solemn dance, and hymeneal rite;

Along the street the new-made brides are led,

With torches flaming, to the nuptial bed:

The youthful dancers in a circle bound

To the soft flute, and cithern's silver sound:

Through the fair streets the matrons in a row

Stand in their porches, and enjoy the show.

Achilles’ shield features two cities, which in turn feature music and dancing. At once, Homer draws our attention not only to the poetic form but also to dance, music, and pictures, demonstrating just how intertwined these forms of art really were to the Ancient Greeks.

It is no wonder, then, that poets like Keats were fascinated by the Ancient Greeks. We know that Keats was inspired by the works of Homer through his “On First Looking into Chapman’s Homer,” a gorgeous poem that describes his initial experience reading through the lines of The Iliad in George Chapman's translation. Similarly, we can see direct parallels between The Iliad’s description of Achilles’ shield and Keats’ own ekphrastic poem “Ode on a Grecian Urn”:

Who are these coming to the sacrifice?

To what green altar, O mysterious priest,

Lead'st thou that heifer lowing at the skies,

And all her silken flanks with garlands drest?

What little town by river or sea shore,

Or mountain-built with peaceful citadel,

Is emptied of this folk, this pious morn?

And, little town, thy streets for evermore

Will silent be; and not a soul to tell

Why thou art desolate, can e'er return.

If you didn’t know that “Ode on a Grecian Urn” was published in 1819, then you might assume it is a continuation of Homer’s description of Achilles’ shield — and because Keats was so influenced by Homer, it might as well be. Keats describes a Grecian urn in the style of ekphrasis, drawing on many of Homer’s descriptive turns of language. He was not the only poet profoundly inspired by Homer’s ekphrastic work.

Writing almost 150 years later in 1952, W. H. Auden would compose the monumental “The Shield of Achilles.” The poem is replete with luscious imagery in the style of Keats and Homer; it is his own interpretation of the legacy of The Iliad's Book 18:

She looked over his shoulder

For ritual pieties,

White flower-garlanded heifers,

Libation and sacrifice,

But there on the shining metal

Where the altar should have been,

She saw by his flickering forge-light

Quite another scene.

You can see direct parallels between Auden’s work and that of Keats: the heifers, the garlands, the ritual sacrifice. It is quite likely that Auden had Keats’ “Ode on a Grecian Urn” in mind when composing his poem, demonstrating the beautiful connection between art and literature across time.

Today, the concept of the "man of culture,” a term that was tossed around mockingly even in the 1860s, is on the decline. Even those rare mortals who fancy themselves scholars of the humanities are often limited by the scope of their own field: the Shakespeare pundit knows nothing of Mozart, and the Nietzschean cannot identify a Brueghel from a Rembrandt. Part of the problem lies in the way that we approach these subjects today: students entering American colleges and universities, for instance, are asked to identify a single major and stick with courses that narrowly pertain to that subject. Even colleges that still mandate a liberal arts curriculum often teach those courses in isolation and without reference to other pertinent subjects. But as Homer, Keats, and Auden’s work teaches us, the importance of a holistic liberal arts education — of understanding one subject in relation to another — can profoundly enhance our understanding of a given work of art.

Contrary to what many of today’s self-referential, solipsistic contemporary artists might have you believe, no work of art lives in a vacuum. In his monumental essay “Tradition and the Individual Talent,” the modernist poet T. S. Eliot tells us that a given work of literature cannot be understood without comprehending the centuries of tradition that came before it. Similarly, as is evident in Eliot’s work that often contains abstruse allusions to visual art and music, literature cannot be understood without a comprehensive humanistic education.

The Romantics knew this well: our friend Keats — as well as poets William Wordsworth and William Blake before him — drew on Edmund Burke and Immanuel Kant’s idea of the sublime in their work, depicting a transcendent worldview borrowed from the philosophical mastermind of the times. Wordsworth himself dabbled in philosophy, and his good friend Samuel Taylor Coleridge was both a philosopher and a theologian. Blake was also a painter and printmaker. The works of the Romantic poets inspired painters such as Caspar David Friedrich, who incorporated the Romantic conception of the sublime into their canvases. In music, Romantic composers such as Franz Schubert and Richard Strauss set poems to song to reveal an additional layer of emotional complexity. Taken as a whole, The Romantic movement — in literature, philosophy, music, and art — is a perfect example of why art cannot be fully understood in isolation. Each form of art speaks to the next, creating an interdisciplinary dialogue among different modes of artistic expression.

As the 19th century poet and cultural critic Matthew Arnold tells us in Culture and Anarchy, culture is the study of perfection. The cultured individual will therefore be the ideal citizen of the world, capable not only of defying myopic worldviews but of grasping the grandeur of civilization in its entirety, expanding the mind through an interplay of ideas. Arnold’s conception of liberal arts education closely mirrors that of Aristotle, and in demonstrating a renewed interest in the Greeks, Arnold makes the case for a universal cultural education that should be required for all citizens of the world regardless of class or status. Culture, after all, is the cornerstone to understanding ourselves. It is, as the Greeks remind us, the central facet of what makes us human.

Because Megan has criticized the art world for making laypeople rely on wall text in galleries and museums to understand Modern and Postmodern art, she would like to point out that our essay is primarily about how art is taught to aspiring artists, who should have a more sophisticated understanding of the layers of meaning in any given artwork. Even so, laypeople also benefit from more liberal arts education. Auden's poetry is beautiful at first read, but it becomes more profound to those who grasp the history behind it.

The Greek education system closely followed the prescription of “healthy body, healthy mind,” a belief so timeless that, in fact, Liza’s alma mater Columbia University mandated Physical Education courses as part of their liberal arts education — in explicit keeping with Aristotle’s idea of the ideal system of education.

Does this justify Bob Dylan’s 2016 Nobel Prize in Literature?