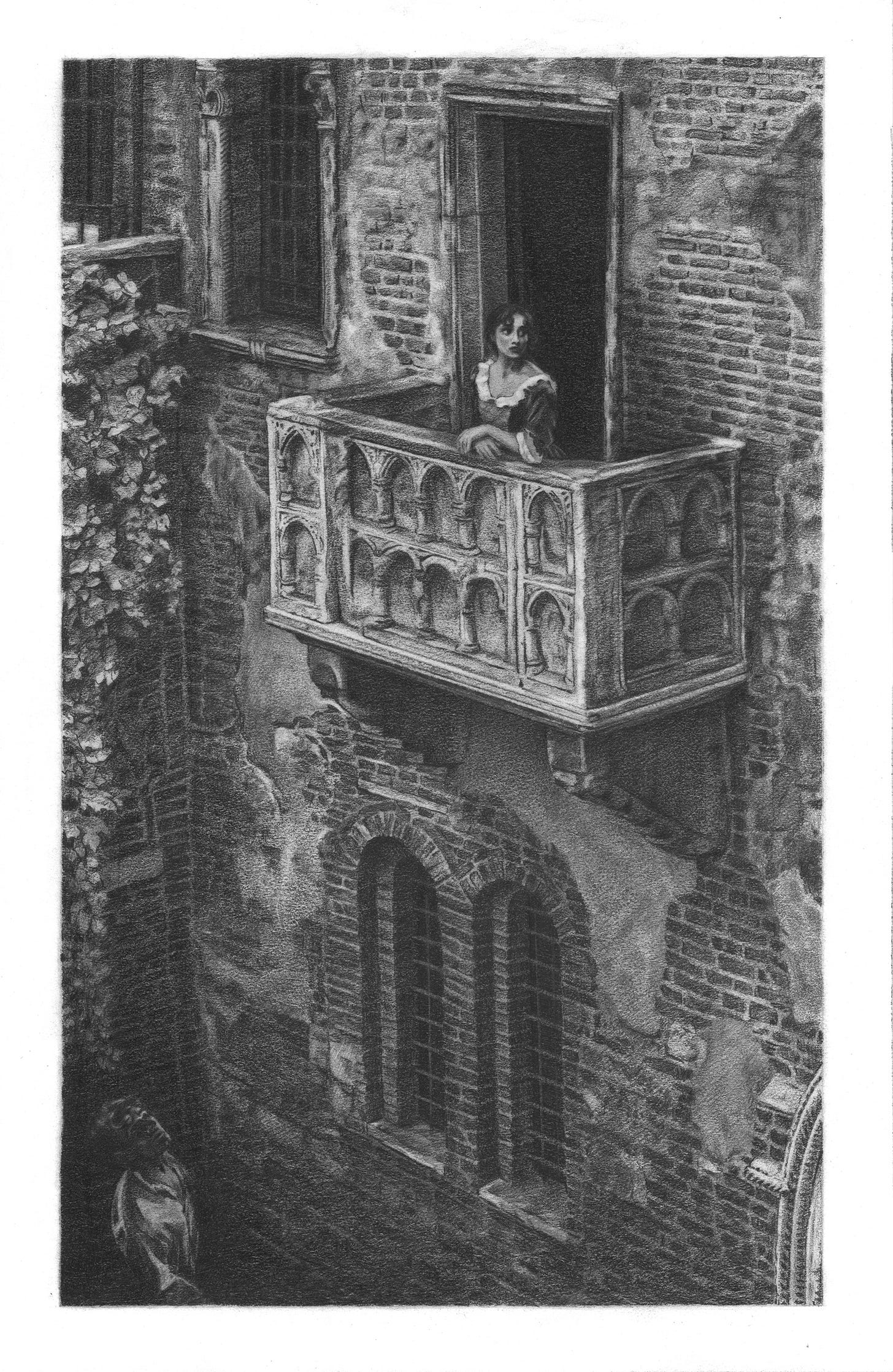

Romeo and Juliet is the most famous of love stories, though sometimes the lovers go by other names. Their tale is both ancient myth and recent history, both a dramatization and the real events that befell actual people. Many young men and women have died to pursue love across the battle lines of feuding clans. The persistence of this story across cultures and centuries demonstrates an enduring tragedy: When feuds entrench generations in violent tit-for-tats, love does not conquer hate.

The clannishness of human nature is best captured by the Bedouin adage, “I against my brother; I and my brother against my cousin; I and my brother and my cousin against the world.” In all its recurrences, Romeo and Juliet is about the casualties of this mindset.

In ancient myth, Ovid shares the story of Pyramus and Thisbe, whose Babylonian families hated each other like the Montagues and Capulets of Verona. Those young lovers whispered sweet nothings through a crack in a wall between their feuding families' homes, and plotted to elope underneath a mulberry tree.

When the young man arrived, he saw a lion with a bloody mouth chewing on Thisbe's veil. He could not know that moments earlier, she had dropped the veil while running away from the beast, and was safely hidden. Blaming himself for not reaching their rendezvous early enough to protect her, Pyramus falls on his sword. As he lay dying, Thisbe came out of hiding:1

And then she saw a quiver

Of limbs on bloody ground, and started backward,

Paler than boxwood, shivering, as water

stirs when a little breeze ruffles the surface.

Clutching his body, Thisbe cries out that neither their wretched parents nor death could keep them apart, and then kills herself with the same sword.

In recent history, Bosko and Admira fell in love right before the Bosnian War imperiled romance between Serbs like him and Muslims like her. They tried to leave besieged Sarajevo together, but a sniper took them out as they ran, holding hands, across a bridge to escape the city. A soldier who witnessed their deaths reported that, “They were shot at the same time, but he fell instantly and she was still alive. She crawled over and hugged him and they died like that, in each other's arms.”

Their bodies were left entwined in no man's land for days, as the threat of rifle fire postponed their burial. Admira's father said that, “War intervened in love — that's the problem. In such situations, the laws of love do not exist. Only the laws of war.” This truism plays out in the opera Aida, which premiered in Cairo in 1871, in which an Egyptian general falls in love with a captured Ethiopian princess while their countries wage war; they suffocate together in a vault.

We restage Romeo and Juliet compulsively. The basic plot — lovers from feuding clans meet a tragic end because of their indiscretion — is one of humanity's major motifs. It has always been our modus operandi to defend group honor with violence, even before we were human and more closely resembled our chimpanzee cousins. For millennia, love affairs have blossomed during blood feuds, so it is no wonder that lovers are sometimes drawn from opposing sides. Our swelling collection of Romeo and Juliet iterations demonstrates the bloodletting that feuds demand from every generation.

Tony and Maria from West Side Story may be the most famous American retelling of Romeo and Juliet, but there is also the real life story of Johnse Hatfield and Roseanna McCoy. These star-crossed lovers managed to consummate their affair, but even after Roseanna became pregnant, their feuding fathers forbade a shotgun wedding. When Johnse found out Roseanna carried his child, he snuck around to see her, which was reason enough for Roseanna's brothers to hunt him down. To save him, Roseanna fashioned a makeshift bridle from a strip of her petticoat, then galloped across a mountain to alert his father (who was also the leader of the Hatfield clan) to his son's peril. She arrived in time for “Devil" Anse Hatfield to rescue Johnse, for which her own father, the McCoy patriarch, disowned her.

Thus Roseanna became estranged from the McCoys, yet even after saving Johnse’s life, Devil Anse would not accept her as his daughter-in-law. When she gave birth to Little Sally, the baby girl never got to know her father before a measles epidemic took her at just three months of life. Legend has it that Roseanna died soon after from a broken heart.2

The Hatfield-McCoy feud began during the American Civil War. Its battle line cut through the Appalachian community where the Hatfields and McCoys lived on the border of eastern Kentucky and West Virginia, providing a handy excuse for repaying petty grudges with greater violence than usual. Both families counted Union and Confederate soldiers among their cousins, and their personal war was more about grievances like stolen razorback pigs than about the character of their nation.

In his comprehensive history of the Hatfield-McCoy feud, Dean King writes:

A blood feud, in the vein of the Hatfields versus the McCoys, or the Montagues against the Capulets of Shakespeare fame, is essentially a state of warfare between two families. Feuds do not always have neat beginnings and ends. A feud can be anything from a revenge killing that occurs many years after the original crime to a complex brew of conditions, grievances, and affronts resulting in violence and retribution.

The first mistake people make regarding the Hatfield-McCoy feud is in arguing over when it began, a disagreement that arose even before the feud ended — though exactly when it ended is also a matter of dispute. Was the feud sparked by the senseless murder of Harmon McCoy at the end of the Civil War? Was it ignited fourteen years later, when Harmon's brother Randall accused Floyd Hatfield of stealing his razorbacks? Or was it Johnse Hatfield's misbegotten love affair with Roseanna McCoy that caused a fury so fierce that it raged out of control?

The answer to these questions is simply: yes. Like a bonfire lit from three different sides, the conflagration grew out of these events — though they occurred over a span of decades — and gained strength from their accumulation.

Republican vice-presidential nominee J. D. Vance recounts in his memoir, Hillbilly Elegy, how he is descended from a key player in the infamous Hatfield clan through his grandfather:

We don't know much about Papaw's early years, and I doubt that will ever change. We do know that he was something of hillbilly royalty. Pawpaw's distant cousin – also Jim Vance – married into the Hatfield family and joined a group of former Confederate soldiers and sympathizers called the Wildcats. When Cousin Jim murdered former Union soldier Asa Harmon McCoy, he kicked off one of the most famous family feuds in American history.

Vance and his ancestors who fought in the Hatfield-McCoy feud are Scots-Irish, which Vance has described as “one of the most distinctive subgroups in America.” He writes in Hillbilly Elegy that:

[The Scots-Irish] distinctive embrace of cultural tradition comes along with many good traits — an intense sense of loyalty, a fierce dedication to family and country — but also many bad ones. We do not like outsiders or people who are different from us, whether the difference lies in how they look, how they act, or, most important, how they talk. To understand me, you must understand that I am a Scots-Irish hillbilly at heart.

Historian David Hackett Fischer argued that Scots-Irish immigrants significantly shaped modern American political culture in his book Albion's Seed. Fischer prefers to call this group of American immigrants “the Borderers,” because they are not precisely Scottish or Irish, but rather the descendants of people who lived along the Scottish-English border in the late 1600s — just as their progeny would live along the Union-Confederate border a couple hundred years later. The Scottish-English border was invaded, plundered, and torched incessantly over the span of 700 years, as the Scottish and English kings vied for control over the region, and this cultivated a striking ruthlessness in the Borderer people who later traveled to the New World in search of a better home.

Fischer explains how brutal conditions shaped a culture of pronounced clannishness and feuds:

Border violence also made a difference in patterns of association. In a world of treachery and danger, blood relationships became highly important. Families grew into clans, and kinsmen placed fidelity to family above loyalty to the crown itself… Borderers placed little trust in legal institutions. They formed the custom of settling their own disputes by the lex talionis of feud violence and blood money.3

Thomas Sowell elaborates on Fischer's history in Conquests and Cultures, with an anecdote about President Andrew Jackson, who descended from the Borderers:

Among the precepts that Andrew Jackson's mother taught him were never to sue anybody for slander or for assault and battery: “Always settle them cases yourself.”4

In his most graphic example of what Borderer feuds looked like, Fischer told of how the “Johnston-Johnson clan adorned their houses with the flayed skins of their enemies the Maxwells in a blood feud that continued for many generation.”5 And then he explains that American hillbilly honor culture inherited the Borderer mindset:

When one man forfeited honor in the backcountry, the entire clan was diminished by his loss. When one woman was seduced and abandoned, all her “menfolk" shared the humiliation. The feuds of the border and backcountry rose mainly from this fact. When “Devil Anse" Hatfield was asked to explain why he had murdered so many McCoys, he answered simply, “A man has a right to defend his family.” And when he spoke of his family, he meant all Hatfields and their kin. This backcountry folkway was strikingly similar to the customs of the borderers.6

Scott Alexander's review of Albion's Seed (which is far easier to digest than Fischer's nine-hundred-page tome) summarizes how the Borderers' grueling origins resulted in “a culture marked by extreme levels of clannishness, xenophobia, drunkenness, stubbornness, and violence.” The 250,000 Borderers who immigrated to Appalachia dwarfed the numbers of other large immigrant groups that helped form the United States; by comparison, Puritan immigrants numbered only 20,000. Thus Borderers had a strong hand in shaping American culture from its infancy, as when they become the cowboys who made the West wild.

Alexander writes:

The Borderers really liked America — unsurprising given where they came from — and started identifying as American earlier and more fiercely than any of the other settlers who had come before. Unsurprisingly, they strongly supported the Revolution — Patrick Henry (“Give me liberty or give me death!”) was a Borderer. They also played a disproportionate role in westward expansion. After the Revolution, America made an almost literal 180 degree turn and the “backcountry” became the “frontier”. It was the Borderers who were happiest going off into the wilderness and fighting Indians, and most of the famous frontiersmen like Davy Crockett were of their number. This was a big part of the reason the Wild West was so wild compared to, say, Minnesota (also a frontier inhabited by lots of Indians, but settled by Northerners and Germans) and why it inherited seemingly Gaelic traditions like cattle rustling.

British journalist Ed West explains the extent of their legacy in America:

Even today this Borderer-dominated region has clear cultural differences to the rest of the United States, with surveys of cultural attitudes showing far higher support for using violence in situations other Americans think inappropriate, and strong support for the military. Many of the most significant figures in American military history were Borderers by descent, among them Ulysses S. Grant and George Patton.

But their political influence has been just as strong, and George MacDonald Fraser described how in 1969 descendants of ‘three notable Anglo-Scottish Border tribes’ gathered for the presidential inauguration in Washington — Billy Graham, Lyndon Johnson and Richard Nixon. Three years later the village of Langholm in Dumfriesshire welcomed the arrival of the Borderers’ most well-travelled son — Neil Armstong.

J. D. Vance is but the latest Borderer son to achieve prominence in American politics, and he is an intriguing figure because his contradictions are conspicuous even by the standards of a politician. Though he once called Donald Trump “America's Hitler" and “political heroin” (a particularly nasty criticism, given Vance's rise to fame as a memoirist of opioid-infused Appalachia), he later renounced his harsh words. Now he has joined Trump's ticket as the vice presidential nominee. He is poised to inherit the MAGA movement. And if his dreams come true, then Vance will someday become president.

As he instructs us in Hillbilly Elegy, Vance should be understood through his Scots-Irish heritage — which includes its hallmark blood feuds. He may seem like a political chameleon, but his core identity is actually consistent. We should expect nothing less from Vance than fierce loyalty to his clan, especially when it feuds with a rival, as MAGA now fights against anyone who opposes Trump.

Anti-Trump conservatives like David Frum, who once mentored Vance, may feel that in the course of pursuing power, Vance betrayed the best qualities of American conservatism to capitalize on Trump's populist movement. But as West points out:

…even voting patterns in 21st-century America still reflect Borderer migration patterns, a trend that became more pronounced with the rise of Donald Trump. The modern Republican Party is in many ways the party of the Borderers.

Vance may have always aimed at becoming the leader of his clan, and true to the Borderer ethos that “might makes right,” it would be wrong if he didn't fight dirty to win. Sowell described how “the ruthless fighting called ‘rough and tumble,’ (which included biting off ears or noses and gouging out eyes) became hallmarks of the Southern backcountry way of life.”7 Becoming a hypocrite to gain power is comparatively tame. But even some Scots-Irish believe that Vance betrayed his clan for personal gain. In “How Rednecks Like Me Hear J. D, Vance,” River Page scoffs:

There’s nothing wrong with changing your mind. People, including politicians, do it all the time. What sets J.D. Vance apart from the fray is the nakedness of his ambition, his self-import. In his memoir, Vance presents the chaos and misfortunes of his family not as communal tragedies but as obstacles that stood in the way of his own personal success, obstacles he — unlike almost everyone else in his family — bravely overcame. Some might call it narcissistic, but in the South we call it uppity.

Similarly, Kentucky governor Andy Beshear recently derided Vance for claiming kinship with his state. Vance grew up visiting his extended family in Jackson, Kentucky, not far from where Johnse Hatfield and Roseanna McCoy had fallen in love. In Beshear's television interview, his southern drawl legitimized his condemnation:

I want the American people to know what a Kentuckian is and what they look like. Because let me just tell you that J. D. Vance ain't from here. The nerve that he has to call the people of Kentucky, of eastern Kentucky, lazy! Listen, these are the hard-working coal miners that powered the Industrial Revolution, that created the strongest middle class the world has ever seen, powered us through two world wars. We should be thanking them, not calling them lazy. So today was an opportunity… to stand up for my people. Nobody calls us names, especially those that have worked hard for the betterment of this country.

This “you don't look like you’re from these parts" saber rattling fits the Scots-Irish temperament that Vance describes in Hillbilly Elegy. Notably, Beshear is in the running to become vice-presidential nominee for the rival clan, the Democratic Party. He may become Vance's foil as American politics descend further into the intractable morass of a violent feud.8

American feuds imperil our experiment in self-governance. Although it has become the status quo in America and much of the world, we would do well to remember that self-governance is an historical aberration. Society has usually been structured within clans, culminating in the largest clan of nationhood headed by a king. Our patriarchs (and occasional matriarchs) achieved power as the heads of families that dominated other families. The American rebellion against King George III overcame the imposition of one very powerful clan's authority, the House of Hanover.

Our revolutionary idea of self-governance holds that might should not make right; instead, the American founders tried to design a system by which disparate peoples could negotiate, collaborate, and compromise while taking turns holding power. What this outlook lacks in swagger, it makes up in the boldness to buck a millennia-long trend of clan-based society, with its accompanying feuds and strongmen. Therefore, although feuds will lay waste to any type of society, George Washington knew that they are particularly noxious to the American Experiment:

The alternate domination of one faction over another, sharpened by the spirit of revenge natural to party dissension, which in different ages and countries has perpetrated the most horrid enormities, is itself a frightful despotism. But this leads at length to a more formal and permanent despotism. The disorders and miseries which result gradually incline the minds of men to seek security and repose in the absolute power of an individual, and sooner or later the chief of some prevailing faction, more able or more fortunate than his competitors, turns this disposition to the purposes of his own elevation on the ruins of public liberty.9

Washington outlined the process by which clan patriarchs can evolve into strongmen and then kings — a position he famously declined in the fragile, formative years of the American Experiment. (Though a significant percentage of American revolutionaries were of Borderer descent, Washington was not.) His warning against the strongmen integral to feuds, who are the law unto themselves, exposes a tragic paradox in Borderer culture.

They rebelled against their king after nearly a millennia of abuse, while simultaneously cultivating a leadership style that undermines the liberal democracy by which they meant to replace him. The American inheritance of Scots-Irish traditions is both fundamental to the nation's character and a handicap on maintaining it.

Another proud Scots-Irishman and author of Born Fighting: How the Scots-Irish Shaped America, James Webb, claims that the Borderers:

…did not merely come to America, they became America, particularly in the south and the Ohio Valley, where their culture overwhelmed the English and German ethnic groups and defined the mores of those regions.

He also proclaimed that they:

…shaped the emotional fabric of the nation, defined America's unique form of populist democracy, created a distinctly American musical style, and through the power of its insistence on personal honor and adamant individualism has become the definition of 'American' that others gravitate toward when they wish to drop their hyphens and join the cultural mainstream.

But as Charles Oliver points out in his review of The Fighting Scots-Irish:

The populist politics they pioneered doesn't necessarily produce the sort of values that sustain liberty.

…

The Scots-Irish came to prize aggressiveness and cunning, and they insisted on choosing their own leaders based on those traits. They developed a distrust of government, which seemed to exist only to burn their homes, seize their property, and kill their kin. And they reserved to themselves the right to judge the laws they lived under and determine whether they would obey them or not. They lived in rough, simple, ill-kept shacks. They saw no reason to build better homes when they were only going to get burned down eventually. They were at once fervently religious and intensely sensual.

Webb and Vance have much in common: They both published a popular book about their cherished Scots-Irish heritage, they both served in the military, they both joined the political fray (Webb served as assistant secretary of defense under Ronald Reagan), and perhaps crucially, they are both men. Indeed, romanticizing Scots-Irish culture seems to be a distinctly masculine fixation.

American men today are more often found on the political right, while American women are exceedingly likely to join the left-wing, so that our embattled political tribes are becoming increasingly sex segregated. At the same time, distaste for inter-political marriage in the U.S. has been on the rise. Where once Americans singled out interracial marriage for opprobrium, today our more salient group difference is left versus right.

After Donald Trump became president in 2016, one in ten Americans said that they ended a romantic relationship because of politics, and one in five personally knew of a couple whose relationship faltered. Two researchers studying this phenomenon wrote that, “if the sexes are making war over political issues, they’re less likely to make love.”

Less likely, but not without precedent.

There is little to be gained in arguing over when it began, or who started it, but it is obvious that the two American political parties are embroiled in a feud. And I have a prediction about how this drama will play out: Somewhere among the millions of embittered Americans, there will be a Romeo and a Juliet.

Ovid, and Rolfe Humphries. “Book Four.” Metamorphoses, Indiana University Press, Bloomington, Indiana, 1955, p. 85.

Johnse ended up marrying Roseanna's cousin Nancy McCoy, and accounts differ over whether he betrayed Roseanna. But according to Dean King's history, Johnse doggedly tried to marry Roseanna even after their infant daughter died, until she told him that “she had experienced too much grief, and too much had passed between them. She was caught in a purgatory somewhere between him and her own family, and she was resigned to staying there. She asked him to leave, and the two never saw each other again.”

See: King, Dean. “Chapter Six: The Wages of Love.” The Feud: The Hatfields and McCoys, The True Story, Back Bay Books / Little, Brown and Company, New York, NY, 2013, p. 82.

Fischer, David Hackett. “Borderlands to the Backcountry.” Albion’s Seed, Oxford University Press, New York, NY, 1989, pp. 628-9.

Sowell, Thomas. “Chapter 2: The British.” Conquests and Cultures: An International History, Basic Books, New York, NY, 1998, p. 78.

Fischer, David Hackett. “Borderlands to the Backcountry.” Albion’s Seed, Oxford University Press, New York, NY, 1989, p. 663.

Fischer, David Hackett. “Borderlands to the Backcountry.” Albion’s Seed, Oxford University Press, New York, NY, 1989, p. 668.

Sowell, Thomas. “Chapter 2: The British.” Conquests and Cultures: An International History, Basic Books, New York, NY, 1998, p. 77.

Whatever the motives of the young man who attempted to assassinate Donald Trump, the attempt on his life has undoubtedly escalated the feud, just as Jan 6 did in the last significant round of violence.

Washington continues:

Without looking forward to an extremity of this kind (which nevertheless ought not to be entirely out of sight), the common and continual mischiefs of the spirit of party are sufficient to make it the interest and duty of a wise people to discourage and restrain it.

It serves always to distract the public councils and enfeeble the public administration. It agitates the community with ill-founded jealousies and false alarms; kindles the animosity of one part against another; foments occasionally riot and insurrection. It opens the door to foreign influence and corruption, which find a facilitated access to the government itself through the channels of party passion. Thus the policy and the will of one country are subjected to the policy and will of another.

There is an opinion that parties in free countries are useful checks upon the administration of the government, and serve to keep alive the spirit of liberty. This within certain limits is probably true; and in governments of a monarchical cast patriotism may look with indulgence, if not with favor, upon the spirit of party. But in those of the popular character, in governments purely elective, it is a spirit not to be encouraged. From their natural tendency it is certain there will always be enough of that spirit for every salutary purpose; and there being constant danger of excess, the effort ought to be by force of public opinion to mitigate and assuage it. A fire not to be quenched, it demands a uniform vigilance to prevent its bursting into a flame, lest, instead of warming, it should consume.

While recognizing Fischer's identification of the Border Scots-Irish as one of the four primary American cultures imported from England in successive waves of migration, you fail to mention the most salient part of their culture for American politics, that their clannishness is carefully cultivated by their cavalier absentee landlords so that they can be exploited century after century by the southern English noble families that own the land they fight upon. This dynamic too emigrated to America, and Vance and Trump are perfect examples of the way elites have always manipulated southern poor whites. You also give the borderers too much importance. That culture and their masters have existed in tension with the egalitarianism of the Puritans and the tolerance of the mid Atlantic dissenters long before the country was founded. Those 20,000 New England Puritans had lots of children and it was their descendants that overwhelmed the South in the Civil War by sheer numbers and industry.

Vance claims kinship with the Backcountry, but filtered through Yale and Silicon valley with his Indian wife he represents the Randolphs, Byrds, and Culpeppers, and Thiels not the ignorant mountain men that worked their land and fought their wars. For all his German/New York origins, Trump is authentically backcountry in his values, ignorance and petty narcissism. Vance is a poor pretender.

Delightful trawl through all these stories and recounts of clannishness and feuding.

"Thisbe cries out that neither their wretched parents nor death could keep them apart"...... a mention of Tristan & Isolde would have been good here?