Amor Fati

How biology forms the parameters of our fate.

Physics may try its damnedest to instill in us existential dread at an incomprehensible universe, but biology will always be the most offensive science. For physics merely deals with the nature of reality, whereas biology contends with our own nature, and so it repeatedly runs up against wishful thinking about who we are. Biology forms the parameters of our fate, and fate treats us harshly.

In the U.S., the traditional complaint against biology comes from creationists who bristle at the Darwinian insinuation that life could develop independent of their god. But it has been 99 years since Americans tuned their radios to hear news of the Scopes Monkey Trial, when H. L. Mencken was nearly run out of Dayton, Tennessee for his sneering dispatches about “the local primates" who put a biology teacher on trial for teaching human evolution — and that was a high-water mark for creationists. Few take their arguments seriously anymore.

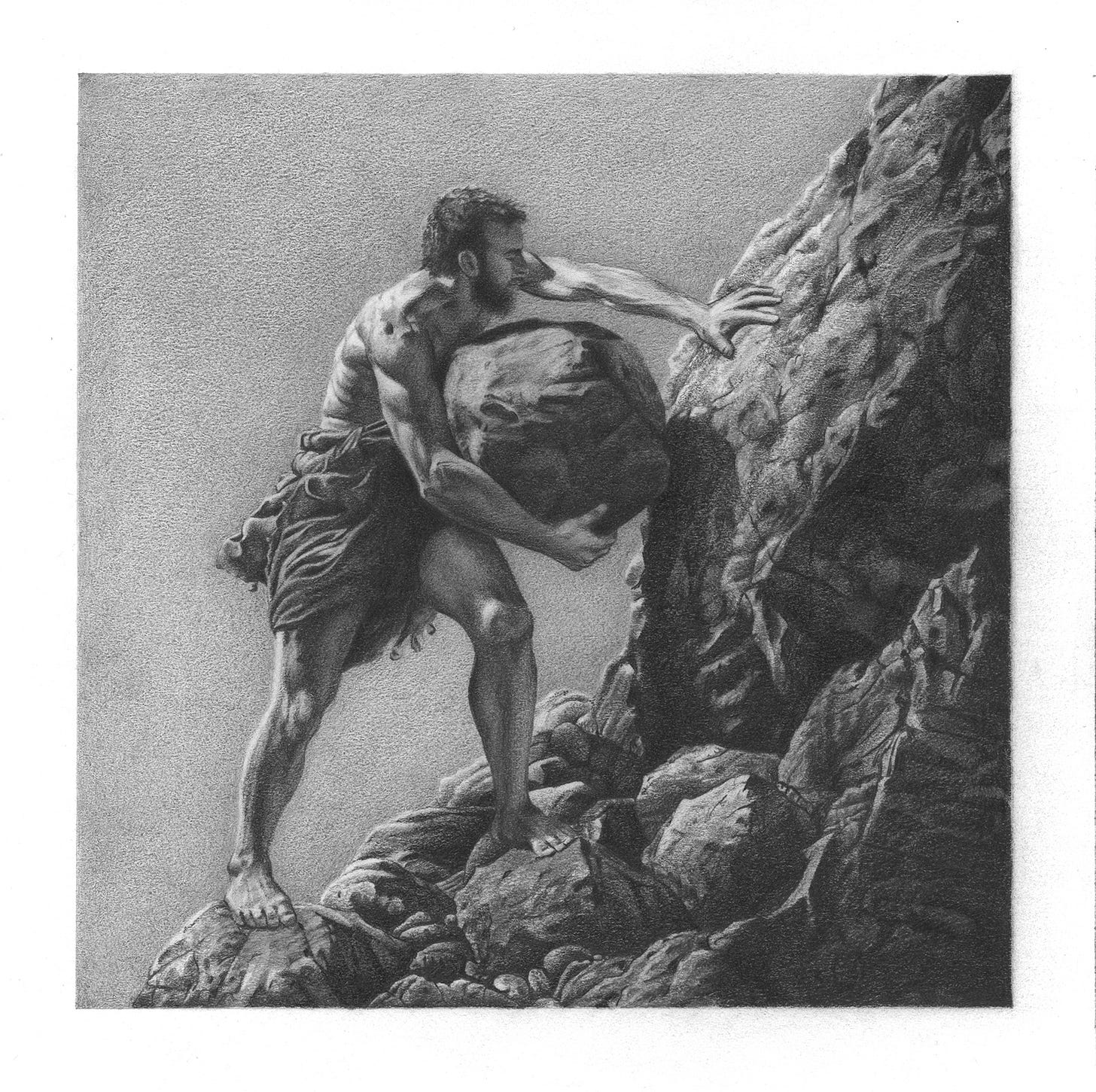

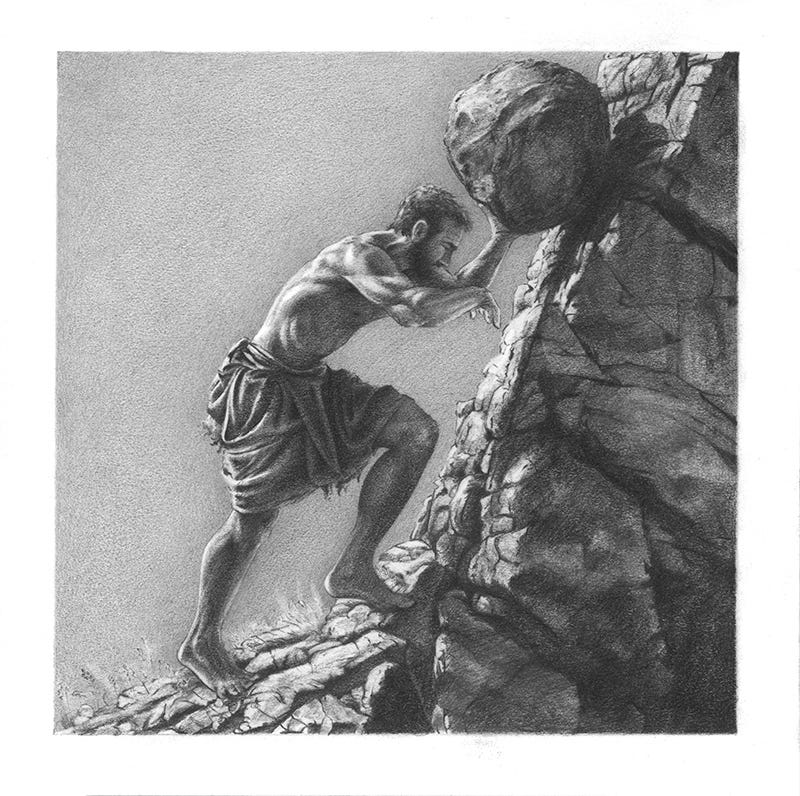

But just as we were about to accept Darwin’s theories, resolution slipped out of our grasp like Sisyphus's boulder tumbling back down the mountainside. He is required to retrieve it and try again, even though the boulder will always escape him right before he can push it up to the summit. This is his eternal task. Because Sisyphus angered the Greek gods, they sentenced him to forever toil for the sake of toil. With similar repetitious labor, we found a new reason to balk at what biology can teach us about ourselves, and so began another arduous hike up the cliffside towards accepting unwelcome truths.

Today, the great stumbling block to understanding biology is sex binary denialism. As we became more comfortable with our kinship to monkeys, we grew uneasy with the irrevocable distinction between men and women. For some who smart at this biological insult, it seems preferable to believe that all of our sex differences are socialized into us, because then they might be within our control — and we would not need to consign ourselves to fate.

We are destined to be either male or female, and this determination shrinks our potential. No human male can ever feel his baby growing inside of him. A woman will never be cast as James Bond. From the outset, we are limited in who we may become. For those who dream of surpassing these constraints, this is one of the fundamental tragedies of the human condition.

In the early 20th century, around the time when John Scopes was accused of teaching human evolution in a Tennessee schoolhouse, scientists began to formally describe the fundamental reason for sex differences: gamete size. Females produce large gametes (eggs) and males produce small gametes (sperm). Other differences between the sexes are secondary to this fundamental cause, and we can understand why these secondary sex characteristics exist by learning how eggs and sperm require separate survival and reproductive strategies. Here is perhaps the earliest definition of sex, which comes from Outlines of General Zoology, a 1924 book by the celebrated zoologist and geneticist Horatio Newman, who also happened to be an expert scientific witness at the Scopes Monkey Trial:1

Sex Defined. – It is not easy to give an adequate definition of sex. Dictionaries define it as “the distinguishing peculiarity of male and female" ; as “either of the two divisions of organic beings distinguished as males and female.” These definitions really evade the issue, but it is very difficult to offer a suitable substitute. We can get at a definition in a somewhat roundabout way by saying that sex comprises that whole set of phenomena that center about gamete reproduction. An individual, then, is sexual if it produces gametes — ova or spermatozoa or their equivalents. Thus we would be justified in calling any individual that produces ova a female, and one that produces spermatozoa a male. One that produces both kinds of gametes is a male-female or, more technically, a hermaphrodite. Thus we may say that the primary sexual characters of individuals are the ova or the spermatozoa, and that maleness or femaleness is determined by the possession of one or the other of these two types of gametes.

Why was it difficult to give an adequate definition of sex? Although sexual dimorphism has always been obvious in complex lifeforms, its cause is microscopic. No one had ever seen a sperm until 1677, when Anton van Leeuwenhoek fashioned an early version of the compound microscope and then examined his own semen. Afterward, it took hundreds of years for scientists to accurately understand how sperm work. Meanwhile, although we had long been familiar with eggs in other animals, we did not find them in ourselves until Karl Ernst von Baar made the discovery in 1827.

In the seventeenth century, scientists dissected dead women in search of proof that our ovaries contain eggs. When they could see no evidence of sperm where they expected to find them in the female reproductive tract, some began to wonder if the male excretion emitted a “seminal vapour” to somehow fertilize women. Others believed that spermatozoa – “semen animals" – were prepackaged people. Leeuwenhoek proposed that “it is exclusively the male semen that forms the foetus and that all the woman may contribute only serves to receive the semen and feed it.” One wonders if he failed to notice the resemblance between mothers and their children, but he was theorizing almost two hundred years before humanity began to grasp the principles of heredity with the publication of Charles Darwin’s On the Origin of Species and then Gregor Mendel's famous pea experiments.

In 1876, scientists finally observed the fusion of egg and sperm for the first time. Then in 1882, Walther Flemming witnessed chromosomes undergoing mitosis. And in 1915, Thomas Hunt Morgan and colleagues published the foundational genetics text, The Mechanism of Mendelian Heredity, after observing the effects of chromosomal inheritance in fruit flies.

Thus by 1924, when Newman first published the definition of sex, scientists had only just figured out how to explain the birds and the bees. Now a century later, many of us are still hazy on the details. Richard Dawkins explains how only “anisogamy” — meaning reproduction with gametes of two different sizes — can comprehensibly explain sexual dimorphism in every species of plant or animal, and in so doing, reveals itself as the fundamental cause of the sex binary:

The anisogamy binary furnishes the oldest and deepest way to distinguish the sexes. There are others, but they are less universally applicable. In mammals and birds, you can do it with chromosomes. Each body cell of a normal human has 46 chromosomes, 23 from each parent. Among these are two sex chromosomes, called X or Y, one from each parent. Females have two Xs, males one X and one Y. Any mammal with a Y chromosome will develop as a male. When a male makes sperm (“haploid”, having only one set of 23 chromosomes), 50 per cent of them are Y sperm, destined to beget sons, and 50 per cent are X sperm, which make daughters. Birds and butterflies have a similar system, but the other way around. It is females that have XY, except that they’re called ZW. In flies, the equivalent of the Y chromosome is a zero. If a fly has two sex chromosomes she’s female. A fly with only one sex chromosome is male. Many reptiles use temperature instead of chromosomes. Turtles that are incubated below 27.7°C develop as male, warmer eggs as female.

Clownfish determine sex not by temperature but by dominance. All but one of the members of a group are male, and like many animals they sort themselves into a dominance hierarchy. There is only one female in the group. When she dies, the dominant male changes sex and becomes the female. What this means in gametic terms is that his testes shrink and ovaries grow instead. The principle of binary sex at the level of micro- and macro-gametes is maintained. Hermaphrodites such as earthworms and land snails have testes and ovaries all in the same body at the same time. Snails are capable of exchanging sperm both ways, having first violently fired harpoons into each other. Angler fish also have both male and female organs in the same body. But it comes about in a curious way. Males are diminutive dwarves; they locate a female, sink their jaws into her body wall, and then become part of her as no more than a tiny testicular excrescence.

If the male angler fish has consciousness, then his fate seems particularly cruel. To fulfill his biological imperative, he must seek oblivion. What did the male angler fish do to anger the gods?

Defining sex according to gamete size has profound explanatory power, because it applies to every complex lifeform, and therefore helps to explain how all life on earth functions. But this definition is not widely understood, and perhaps the most common misconception is that sex is defined by chromosomes. Zachary Elliott, founder of the Paradox Institute, clarifies why chromosomes offer insufficient explanatory power to define sex, even as they play the crucial role in determining sex in human beings:

Based on this definition [with respect to gamete type], we know whether an individual is male or female by looking at the structures that support the production (gonads) and release (genitalia) of either gamete type. In other words, we look at whether the individual develops a body plan organized around small gametes or large gametes. In humans, sex is binary and immutable. Individuals are either male or female throughout their entire life cycle.

In humans, sex is determined by genes. In biology, determining sex does not mean “observing” or “identifying sex” in the colloquial sense. Instead, determining sex is a technical term for the process by which genes trigger and regulate differentiation down the male or female path in the womb. This determines the structures that can support the production and release of either gamete type, and thus, the individual’s sex.

There are many different sex determination mechanisms across species. Humans and other mammals use genetic sex determination, where certain genes trigger male or female development, whereas reptiles often use temperature sex determination, where certain temperature values trigger male or female development. In all these species, an individual’s sex is defined with respect to gamete type and identified by the structures that support the production and release of either gamete.

Thus, while there are various mechanisms that control male and female development, there are still only two endpoints: male and female.

Even within the human species, chromosomal sex determination involves rare variations. These developmental disorders can cause unusual combinations of chromosomes. But there are no exceptions to the rule that there are only two types of gametes. Because no sexually reproducing organism, human or otherwise, has ever produced a third type of gamete, the definition of sex — females produce large gametes, males produce small gametes — is entirely stable. Elliott offers some examples:

Almost always, the Y chromosome determines sex in humans: those with a Y chromosome develop as males, and those without the Y chromosome develop as females. Males usually have 46:XY and females usually have 46:XX.

However, rare errors of cell division during meiosis can result in a translocation or mutation of genes within the chromosomes, and this can result in a sex opposite of what is expected from the chromosomes. For example, 1 in 20,000 births result in males with XX chromosomes. This happens when the SRY gene (the male sex determining region on the Y chromosome) is translocated to an X chromosome during cell division in the father’s reproductive cells. When the fetus is conceived, they receive XX [SRY]. SRY triggers a cascade of genes leading to male development: gonadal differentiation into testes, which then leads to the development of male internal and external genitalia.

Though they cannot produce sperm, since this requires the AZF region from the Y chromosome, XX males are defined as male because they develop the phenotype that produces small gametes (determined by genetics).

Another example for why we cannot use sex determination mechanisms like chromosomes as the definition of sex involves a rare case of a pregnant female with XXY chromosomes. At conception, the lack of an SRY gene on the Y chromosome and the presence of two X chromosomes allowed transcription factors like WNT4 and RSPO1 to develop complete ovaries. The lack of testes and the subsequent lack of anti-Mullerian hormone and testosterone then allowed for full development of female internal and external genitalia (oviducts, uterus, cervix, vagina, and vulva).

She is defined as female, despite the presence of the Y chromosome, because she developed the phenotype that produces large gametes (determined by genetics).

Both cases, and many others, reinforce the important distinction between the mechanisms that determine sex and sex itself.

Despite the impressive explanatory power of defining sex by gamete type, it has been eschewed by some prominent academics and activists. The sexologist Anne Fausto-Sterling of Brown University helped pioneer sex binary denialism with her 1993 essay “The Five Sexes,” which she revisited and updated in 2000. In her zest to “revamp our sex and gender system,” Fausto-Sterling sows confusion by simply ignoring the only reliable definition of sex:

In the idealized, Platonic, biological world, human beings are divided into two kinds: a perfectly dimorphic species. Males have an X and a Y chromosome, testes, a penis and all of the appropriate internal plumbing for delivering urine and semen to the outside world. They also have well-known secondary sexual characteristics, including a muscular build and facial hair. Women have two X chromosomes, ovaries, all of the internal plumbing to transport urine and ova to the outside world, a system to support pregnancy and fetal development, as well as a variety of recognizable secondary sexual characteristics.

That idealized story papers over many obvious caveats: some women have facial hair, some men have none; some women speak with deep voices, some men veritably squeak. Less well known is the fact that, on close inspection, absolute dimorphism disintegrates even at the level of basic biology. Chromosomes, hormones, the internal sex structures, the gonads and the external genitalia all vary more than most people realize. Those born outside of the Platonic dimorphic mold are called intersexuals.

In her influential essay, Fausto-Sterling never discusses gametes. But in her subsequent book Sexing the Body, which is considered a classic text in sexology, the word “gamete" finally appears once at the end. She directly responds to critics of the essay in a closing chapter, where she writes:

When referring strictly to reproduction, it is certainly true that, as a species, humans have binary gametes — there are eggs and there are sperm. These sex cells are definitely a product of evolution. But the moment we move from sex cells to whole human beings… we lose the certainty of binary classification… within the categories of male and female, there is a great deal of individual variation. Among both sperm-bearing and egg-bearing people, we find those who are tall or short, broad-shouldered or slight, with varying degrees of body hair or voice timbres, etc. This variability results from environment (nutrition, exercise, etc.), genetic variation, and from the fact that — as discussed in my op-ed — sexual development itself is not strictly either/or. What happens to genetic, hormonal, fertile people who are, from all these measures, “correctly" classified as male or female but who don't look or sound the part because they are a broad-shouldered female with a deep voice, or a slightly built male with a high voice? Forcing them to label in accordance with chromosomes2 rather than develop a self-presentation and gender identity that matches their lived bodies and experiences can put them in danger.

Here, the sexologist reveals her motive for obfuscating the definition of sex: she does not want it to contribute to our tragedies. But Fausto-Sterling's fear of sexist stereotypes led her to fully embrace them. Faced with the bully scoffing “you aren't a real man,” her stance amounts to saying, “true enough!” But if Fausto-Sterling could overcome her sex binary denialism, then she would find a far stronger rebuttal, like the one articulated by Andrew Sullivan, a writer who was instrumental in convincing Americans to legalize gay marriage:

The sex binary is intrinsic to the survival of our species. That’s just biology and human reproductive strategy. Aggregate sex differences — physical, psychological, behavioral — are deeply rooted in our species’ DNA. They’re not going away because a bunch of Foucault disciples want them to.

But gender is not sex; it’s how that sex is expressed and manifested. And if the range of ways to express or describe your sex as man or woman is expanding and evolving, that’s a huge win for our culture. It means that many more interpretations of what it is to be a man or a woman are now socially acceptable, liberating people from the expectations of crude gender stereotypes.

…

The combination of a sex and a singular personality is always unique. And what is well worth leaving behind is a crude, binary sense of gender itself. Unlike sex, it really is a spectrum. And it can be crushing for gender-non-confirming kids and adults to live up to stereotypes of their gender; and it can be horribly restrictive for everyone else. There will always be social and cultural group differences in the aggregate, for sure — more men, for example, will, on average, prefer watching sports than women. But a woman who loves football is absolutely no less a woman for it.

Sullivan has firsthand experience with the tragedy that Fausto-Sterling frets over, but also the wisdom to see how denying the sex binary cannot solve the problem. He continues:

As a kid, my otherness didn’t have a name. I knew I was a boy — but the day each week that terrorized me the most in my high school was the day I was made to play rugby. I was small, pre-pubescent at that point, bookish, asthmatic, and physically awkward. Being tackled by a post-pubescent boy twice my size and finding my head pushed into knee-deep mud, mixed with my own blood, on a semi-regular basis was not exactly my idea of a pleasant afternoon. Neither was being outside in the cold, endless rain, my hands so frozen I couldn’t actually unbutton my own rugby shirt afterward, my lungs spasming with another asthma attack.

But the fear of this organized male violence was made much worse because it seemed to impugn my maleness. There were no varying, mixed or subtle models of masculinity in my childhood and adolescence that I could easily identify with. When in elementary school I was ingenuously asked by a girl “Are you sure you’re not a girl?” my response was an immediate no. But I knew what she was getting at. And it ate away at my self-esteem.

Similarly, at my grandparents one Christmas, my grandmother noticed me in a corner with a book and my younger brother, who was driving a toy truck up and down the carpet, crashing it into the walls. She said to my mother, looking at my brother, and in front of me, “Well at least you now have a real boy.” It cut deeply. I remember not pursuing English literature past the age of sixteen, even though I loved it — because studying history was somehow, in my mind, more masculine.

Stereotypes harmed Sullivan as a young gay boy, but at the same time, they impoverished the life of his heterosexual father. They can oppress every type of person:

To deepen the self-inflicted wound, my dad was a near model of classic masculinity. He was a superb athlete who had competed for England as a middle-distance runner; he had been captain first of his high school rugby team and then of our town’s. He was taciturn and bloody-minded, threw his weight around in our house, fished in the North Sea, raised rabbits and chickens, and drove fast. He routinely knocked down parts of our little house whenever he felt bored to add extensions, which he rarely finished. His mates drank lots of beer, and it was clear he was much happier among them than with his own family. He even had a mid-life crisis, and bought a racy car and a leather jacket. It was as if he felt the need to act out a near-parody of “toxic masculinity.”

He wasn’t cruel to me, but he never came to any of the school plays I was in, or any of my debating contests. Too girly, I suppose. And of course I felt as if I had let him down. I remember with more than a little poignancy how he once gamely tried to teach me how to kick a soccer ball. And how utterly useless I was.

What he didn’t let himself experience to its fullest for a long time was another side of himself. He loved to draw and to paint. After his death a year ago, we found a letter that showed he had once been admitted to the Slade School of Fine Art in London, perhaps the finest such institution in the country, and a great honor. He never told us of this, and I don’t know why he turned down the place. Probably his need to earn money, but maybe also the price of gender-conformity. But as soon as he retired, and especially after he got divorced, he started painting again — and the results were spectacular. I cannot help but wonder what kind of life he might have had, if he had had the courage of his own, non-conforming desire, what great paintings he might have produced over time.

When I came out to him, he suddenly bent down and sobbed. I was shocked and confused. My dad never cried. I asked him again and again why he was weeping, even as I was relieved he hadn’t thrown a punch. And after a while, he looked up and said something I will never forget: “I’m crying because of all you must have gone through growing up, and I never did anything to help you.” All that macho bravado dissolved instantly by a father’s love.

Later that day, my mother, with her usual blather-mouth said she thought he was crying because he realized that I had had the nerve to risk my career and future to be who I truly was, and he had never summoned up the courage to do the same. He was, she said, crying for himself. Not that he was gay, but that he loved art. A weight of gender expectations may well have prevented him from realizing his dream.

Like Sullivan, we do not need to deny the sex binary in order to defy the sex stereotypes. Though we are fated to be male or female, we are not fated to all be male or female in the same way — even biology is not that offensive. And yet, perhaps because those stereotypes could not exist without the sex binary undergirding our reality, a new taboo has emerged against biological fact.

Dawkins sympathizes with why it might seem intuitive that the sex binary could actually be a spectrum. After all, as he points out, nearly everything else is. But he notes that this distinction between the males who produce small gametes and the females who produce large gametes is in fact a rare example of a “true binary":

Everywhere you look, smooth continua are gratuitously carved into discrete categories. Social scientists count how many people lie below “the poverty line”, as though there really were a boundary, instead of a continuum measured in real income. “Pro-life” and pro-choice advocates fret about the moment in embryology when personhood begins, instead of recognising the reality, which is a smooth ascent from zygotehood… Anthropologists quarrel over whether a fossil is late Homo erectus or early Homo sapiens. But it is of the very nature of evolution that there must be a continuous sequence of intermediates.

…

Tall vs short, fat vs thin, strong vs weak, fast vs slow, old vs young, drunk vs sober, safe vs unsafe, even guilty vs not guilty: these are the ends of continuous if not always bell-shaped distributions. As a biologist, the only strongly discontinuous binary I can think of has weirdly become violently controversial. It is sex: male vs female. You can be cancelled, vilified, even physically threatened if you dare to suggest that an adult human must be either man or woman. But it is true; for once, the discontinuous mind is right. And the tyranny comes from the other direction, as that brave hero JK Rowling could testify.

The controversy engulfing J.K. Rowling demonstrates how potent the sex binary taboo has become. She was arguably the most beloved living author until she defied it, and then her stature threatened to defang the taboo if its defenders failed to loudly condemn her transgression. It began in the summer of 2020 — already a contentious season, amidst the burgeoning COVID-19 plague and riots erupting after a policeman killed George Floyd — when she tweeted:

If sex isn’t real, there’s no same-sex attraction. If sex isn’t real, the lived reality of women globally is erased. I know and love trans people, but erasing the concept of sex removes the ability of many to meaningfully discuss their lives. It isn’t hate to speak the truth.

The idea that women like me, who’ve been empathetic to trans people for decades, feeling kinship because they’re vulnerable in the same way as women – ie, to male violence — ‘hate’ trans people because they think sex is real and has lived consequences — is a nonsense.

I respect every trans person’s right to live any way that feels authentic and comfortable to them. I’d march with you if you were discriminated against on the basis of being trans. At the same time, my life has been shaped by being female. I do not believe it’s hateful to say so.

As Megan Phelps-Roper reported in The Free Press for her podcast miniseries The Witch Trials of J.K. Rowling, “It's hard to capture the breadth of the firestorm that followed.”:

Rowling’s words led to a “revolt” among the staff at one of her publishers, an outcry from some of her most ardent fans, and a torrent of negative headlines in news outlets around the globe. Actors who had grown up on the Harry Potter film sets—people she had known since they were children—distanced themselves from her. Many of Rowling’s former fans began calling for boycotts. They removed photos of her from their websites and Potter tattoos from their bodies. TikTokers started a trend of covering her name on books and book jackets, and tore her books apart. Players of Quidditch—the fictional sport she invented—ultimately changed its name to dissociate themselves from her. The abhorrence of Rowling has at times been so intense that it’s led to the actual burning of her books. A recent novel even includes a scene where Rowling herself is killed in a fire.

Soon after, Rowling published an essay to answer the question, “So why am I doing this? Why speak up?” Her explanation is an inversion of Fausto-Sterling's worries. While the sexologist thinks that admitting to the immutable sex binary hurts people, it is the fantasy author who believes that denying reality is what truly causes harm — often to young women in particular:

I’m concerned about the huge explosion in young women wishing to transition and also about the increasing numbers who seem to be detransitioning (returning to their original sex), because they regret taking steps that have, in some cases, altered their bodies irrevocably, and taken away their fertility. Some say they decided to transition after realising they were same-sex attracted, and that transitioning was partly driven by homophobia, either in society or in their families.

Most people probably aren’t aware — I certainly wasn’t, until I started researching this issue properly — that ten years ago, the majority of people wanting to transition to the opposite sex were male. That ratio has now reversed. The UK has experienced a 4400% increase in girls being referred for transitioning treatment. Autistic girls are hugely overrepresented in their numbers.

The same phenomenon has been seen in the US. In 2018, American physician and researcher Lisa Littman set out to explore it. In an interview, she said:

‘Parents online were describing a very unusual pattern of transgender-identification where multiple friends and even entire friend groups became transgender-identified at the same time. I would have been remiss had I not considered social contagion and peer influences as potential factors.’

Littman mentioned Tumblr, Reddit, Instagram and YouTube as contributing factors to Rapid Onset Gender Dysphoria, where she believes that in the realm of transgender identification ‘youth have created particularly insular echo chambers.’

Her paper caused a furore. She was accused of bias and of spreading misinformation about transgender people, subjected to a tsunami of abuse and a concerted campaign to discredit both her and her work. The journal took the paper offline and re-reviewed it before republishing it. However, her career took a similar hit to that suffered by Maya Forstater.

Maya Forstater lost her job at a London think tank for tweeting that it’s impossible for humans to literally change their sex. When she sued, the judge in her 2019 employment tribunal ruled that her witness statements — “sex is a biological fact and is immutable. There are two sexes. Men are male. Women are female. It is impossible to change sex” — were “not worthy of respect in a democratic society.” But last year, Forstater won her case upon appeal, when three London judges ruled that she had been discriminated against for her belief in biological reality.

Similar examples abound, particularly in the UK, as when Dame Jenni Murray, the longtime presenter of BBC Radio 4’s Woman's Hour, was publicly pilloried in 2017 for writing an op-ed in which she “merely asked the trans activists to acknowledge the difference between sex and gender, a trans woman and a woman.” Around the same time, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, the Nigerian novelist made famous when Beyoncé sampled her feminist TED talk, was condemned for insisting that “trans women are trans women" in defiance of the sacrosanct slogan, “Trans women are women.” These statements are not provocative to many transgender people, who paid a pound of flesh to best express the gender opposite their sex, and to whom it is painfully obvious that their efforts to rebel against fate inevitably butt up against biological constraints.

But activists imposing the taboo doubled down. Chase Strangio, an ACLU lawyer, jeered, “Hey JK Rowling and the other TERFs, a reminder that ‘biological sex’ isn’t what you think it is,” with a link to a Teen Vogue video that features Strangio alongside other activists explaining “5 Misconceptions about Sex and Gender.” Like Fausto-Sterling before them, the Teen Vogue activists studiously avoid any mention of gamete size in their infomercial.

As a mainstream effort to educate followers of Teen Vogue, this video provides a case study in the kind of sex binary denialism vying to influence the youth. It opens with an intersex model declaring that “The binary is bullshit.” Katrina Karkazis, an anthropologist at Amherst College, rolls her eyes while explaining:

Over history, the location or the idea of what determined one's true sex shifted. A hundred years ago it used to be whether or not you had ovaries or testes, then it shifted to what kinds of chromosomes that you had. But the body doesn't just have one place where we can sit there, with a microscope or something else, and say hey wait a second, this is really who you are, this is your true sex. In fact, who you are is who you say you are.

But of course, it was precisely the invention of the microscope that enabled us to see our gametes, which made it possible to find the place in our bodies where binary sex can be defined. Foregoing actual history, the video pivots to a transgender woman insisting, “When I say I'm a woman, I don't just mean that I identify as a woman, I mean that my biology is the biology of a woman, regardless of whether or not doctors agree,” before returning to Prof Karkazis complaining that “Too many people still believe that there’s such a thing as a true sex, and that it comes from your chromosomes. It's not the case. Science has known this for decades, and it's actually a consensus in science and uncontroversial.” But she does not go on to explain how scientists have known for a full century that the only reliable definition of sex is according to gamete size.

The Teen Vogue activists conclude by condemning the statement, “Trans women are biological men,” as “definitely a cringe-worthy misconception.” Strangio pounds his hand, commanding, “We should never talk about any woman who is trans as a man. Not a ‘biological man.’ Not a ‘natal man.’ Not ‘really a man.’” They all insist that “a trans woman's biology is female biology.”

Some transgender activists reject sex binary denialism just as forcefully as Strangio and Teen Vogue insist upon it, such as “trans elder" Buck Angel. The “man with a female past" advocates for pubic acceptance of gender nonconformity, but also against the taboo around innate and immutable sex differences. This has earned him enemies:

Every day, I’m called a new name. Sometimes it’s something obviously insulting, like bigot or transphobe. Sometimes it’s something more subtly designed to twist my knickers, like female. My critics assume this will wound me, because for the last 30 years, I have lived as a man. I medically transitioned at age 30, after what felt like a lifetime of struggle, and after many years of therapy and evaluation.

Transition saved my life. But being called female doesn’t hurt me, because while I changed my body, I’m well aware that I can’t change my sex. And even though I’ve felt since I was a young child that I would have preferred to be—and should have been—born male, I don’t believe that children should medically transition. I’m one of the oldest and most visible female-to-male transsexuals in the country, but because of my views, today’s trans activists not only don’t speak for me, they try to cancel me.

Angel experienced the formation of our new taboo up close:

Then several things started to change. The word transsexual—a person of one sex who changes their body to appear more like the other—was eclipsed by the word “transgender,” an umbrella term that included everyone from tomboys gently rejecting stereotypes to trans women who’d had penectomies, plus myriad gender identities that seemed to have no locatable meaning. The idea that people could actually change sex, that sex was mutable or unreal, took hold in society, especially with young people.

Then, as some clinicians, including trans women, have admitted, a rash of teen girls started to declare themselves trans and transition; some said they’d had no mental health treatments before doing so. Then I started to hear about and from detransitioners, who’d taken cross-sex hormones or had breast or genital surgeries, not to cure some kind of organic dysphoria but because they’d been taught that if they felt uncomfortable with themselves or their bodies, maybe they needed to change them to match their brains. One study of detransitioners showed 55 percent felt they weren’t properly evaluated.

In her essay, Rowling empathizes with why these young women would want to escape their fate:3

The more of their accounts of gender dysphoria I’ve read, with their insightful descriptions of anxiety, dissociation, eating disorders, self-harm and self-hatred, the more I’ve wondered whether, if I’d been born 30 years later, I too might have tried to transition. The allure of escaping womanhood would have been huge. I struggled with severe OCD as a teenager. If I’d found community and sympathy online that I couldn’t find in my immediate environment, I believe I could have been persuaded to turn myself into the son my father had openly said he’d have preferred.

When I read about the theory of gender identity, I remember how mentally sexless I felt in youth. I remember Colette’s description of herself as a ‘mental hermaphrodite’ and Simone de Beauvoir’s words: ‘It is perfectly natural for the future woman to feel indignant at the limitations posed upon her by her sex. The real question is not why she should reject them: the problem is rather to understand why she accepts them.’

As I didn’t have a realistic possibility of becoming a man back in the 1980s, it had to be books and music that got me through both my mental health issues and the sexualised scrutiny and judgement that sets so many girls to war against their bodies in their teens. Fortunately for me, I found my own sense of otherness, and my ambivalence about being a woman, reflected in the work of female writers and musicians who reassured me that, in spite of everything a sexist world tries to throw at the female-bodied, it’s fine not to feel pink, frilly and compliant inside your own head; it’s OK to feel confused, dark, both sexual and non-sexual, unsure of what or who you are.

I want to be very clear here: I know transition will be a solution for some gender dysphoric people, although I’m also aware through extensive research that studies have consistently shown that between 60-90% of gender dysphoric teens will grow out of their dysphoria. Again and again I’ve been told to ‘just meet some trans people.’ I have: in addition to a few younger people, who were all adorable, I happen to know a self-described transsexual woman who’s older than I am and wonderful. Although she’s open about her past as a gay man, I’ve always found it hard to think of her as anything other than a woman, and I believe (and certainly hope) she’s completely happy to have transitioned. Being older, though, she went through a long and rigorous process of evaluation, psychotherapy and staged transformation. The current explosion of trans activism is urging a removal of almost all the robust systems through which candidates for sex reassignment were once required to pass.

Few experience the harsh reality of the sex binary more than detransitioners, who transition but later change their minds. Many live with life-long, irreparable modifications that cause anxiety about “passing" as their genuine sex. And there is a pattern: detransitioners frequently say they tried to become men because they dreaded their female fate.

In the following case studies, I put examples of this pattern in bold. First consider Roxxanne “Tiger" Reed, who lived as a man for 13 years, but last month wrote about her choice to begin detransitioning:

To understand how I decided to transition requires going back to my childhood. I was born in Miami in 1980 and named Roxxanne. I never met my father. He died from a heroin overdose when I was young. My mother was addicted to drugs, too, and the last time I saw her I was in my early twenties. She passed away in 2023. When I was two years old, I was sexually assaulted by a stranger, which resulted in my being put in foster care.

I moved in and out of foster care throughout my childhood, in between stints living with my maternal grandparents, who were divorced. My grandmother was extremely poor and troubled, and ultimately had a mental breakdown, which led me back to foster care. My grandfather, a severe alcoholic, was both verbally and physically abusive.

I knew from an early age that I was a lesbian, and I remember around the age of seven lying in bed wondering why I didn’t have a penis. Throughout my life, I’ve been bullied for my more masculine appearance. I was called names like boy, faggot, dyke, and he-she, among others. I’ve also been sexually abused multiple times by both strangers and family members. When I was 17, I was diagnosed with debilitating endometriosis, which caused me to have painful periods and sent me on a monthly hormonal roller coaster.

As I look back, I see how all this shaped my sense that becoming a woman would mean subjecting myself to a lifetime of assault and abuse, and experiencing relentless mental and physical pain.

In his 2018 Atlantic cover story “When Children Say They're Trans,” Jesse Singal tells of a young woman who wishes she hadn't started taking testosterone at age 16 and then gotten a double mastectomy at age 17:

Max recalled that as early as age 5, she didn’t enjoy being treated like a girl. “I questioned my teachers about why I had to make an angel instead of a Santa for a Christmas craft, or why the girls’ bathroom pass had ribbons instead of soccer balls, when I played soccer and knew lots of other girls in our class who loved soccer,” she said.

She grew up a happy tomboy—until puberty. “People expect you to grow out of it” at that age, she explained, “and people start getting uncomfortable when you don’t.” Worse, “the way people treated me started getting increasingly sexualized.” She remembered one boy who, when she was 12, kept asking her to pick up his pencil so he could look down her shirt.

“I started dissociating from my body a lot more when I started going through puberty,” Max said. Her discomfort grew more internalized—less a frustration with how the world treated women and more a sense that the problem lay in her own body. She came to believe that being a woman was “something I had to control and fix.” She had tried various ways of making her discomfort abate—in seventh grade, she vacillated between “dressing like a 12-year-old boy” and wearing revealing, low-cut outfits, attempts to defy and accede to the demands the world was making of her body. But nothing could banish her feeling that womanhood wasn’t for her. She had more bad experiences with men, too: When she was 13, she had sex with an older man she was seeing; at the time, it felt consensual, but she has since realized that a 13-year-old can’t consent to sex with an 18-year-old. At 14, she witnessed a friend get molested by an adult man at a church slumber party. Around this time, Max was diagnosed with depression and generalized anxiety disorder.

In ninth grade, Max first encountered the concept of being transgender when she watched an episode of The Tyra Banks Show in which Buck Angel, a trans porn star, talked about his transition. It opened up a new world of online gender-identity exploration. She gradually decided that she needed to transition.

…

Today, Max identifies as a woman. She believes that she misinterpreted her sexual orientation, as well as the effects of the misogyny and trauma she had experienced as a young person, as being about gender identity.

Singal also shares Cari Stella's story:

Stella, now 24, socially transitioned at 15, started hormones at 17, got a double mastectomy at 20, and detransitioned at 22. “I’m a real-live 22-year-old woman with a scarred chest and a broken voice and a 5 o’clock shadow because I couldn’t face the idea of growing up to be a woman,” she said in a video posted in August 2016. “I was not a very emotionally stable teenager,” she told me when we spoke. Transitioning offered a “level of control over how I was being perceived.”

Here are just two more examples, both from a 2022 special report in Reuters, “Why detransitioners are crucial to the science of gender care":

“The life of a woman was bleak to me,” [Max] Lazzara told Reuters. “I worried that I would have to get married to a man someday and have a baby. I wanted to run far away from that.”

In early 2011, when Lazzara was 14, she started questioning her gender identity. After discovering forums on Tumblr where young people described their transitions, she felt like something snapped into place. “I thought, ‘Wow, this could explain why my whole life felt wrong.’”

During the summer of that year, Lazzara changed her name and began experimenting with presenting as more masculine. It felt good to cut her hair and wear gender-neutral or men’s clothing. She took medications and received therapy to treat bipolar disorder. But it wasn’t enough to alleviate her distress. In April 2012, Lazzara was admitted to the hospital at the University of Minnesota after a fourth suicide attempt.

Three weeks later, she sought care at the university’s Center for Sexual Health, where she was diagnosed with gender identity disorder. Lazzara told the clinic she was “sure of my identity,” according to her medical records. She wanted hormones and surgeries, the records show, including a mastectomy, a hysterectomy, and liposuction to slim her legs and hips. She was horrified at her body, could not look down in the shower and felt “absolute dread at the time of menstrual cycle,” the records note.

“I felt so strongly. I thought nothing would change my mind,” Lazzara told Reuters.

Clinicians at the university warned families that their children were suicidal “because they are born in the wrong bodies,” Lazzara’s mother, Lisa Lind, told Reuters. “I thought, ‘I’ll do whatever it takes, so she doesn’t kill herself.’”

Lazzara started taking testosterone in the fall of 2012, at age 16. She was still binding her breasts — so tightly, she said, that her ribs deformed. After a man groped her on the street, she decided to have breast-removal surgery, tapping the college fund her grandmother had left for her to cover the nearly $10,000 cost.

Initially, Lazzara was happy with her transition. She liked the changes from taking testosterone — the redistribution of fat away from her hips, the lower voice, the facial hair — and she was spared the sexist cat-calling that her female friends endured. “I felt like I was growing into something I wanted to be,” Lazzara said.

But her mental health continued to deteriorate. She attempted suicide twice more, at ages 17 and 20, landing in the hospital both times. Her depression worsened after a friend sexually abused her. She became dependent on prescription anti-anxiety medication and developed a severe eating disorder.

During the summer of 2020, Lazzara was spiraling. She realized she no longer believed in her gender identity, but “I didn’t see a way forward.”

That October, Lazzara was working as a janitor in an office building in the Seattle area when she caught her reflection in a bathroom mirror. For the first time, she said, she saw herself as a woman. “I had not allowed myself to have that thought before,” she said. It was shocking but also clarifying, she said, and “a peaceful feeling came over me.”

The second Reuters interview is with 22-year-old K.C. Miller, who started treatment for gender dysphoria at age 16, and said, “I absolutely would not have done this if I could go back and do it again.” Her doctor Linda Hawkins observed:

Miller had an extensive history of sexual abuse by a family member starting at age 4, and that as a result, Miller had already been diagnosed with anxiety and post-traumatic stress disorder. Miller had been admitted to a psychiatric hospital for 10 days because of suicidal thoughts in late 2016.

While in the hospital, Miller told her mother she wished she wasn’t a girl “because then the abuse would not have happened,” Hawkins wrote. Elsewhere in the records, Hawkins noted that “Mom expresses concern that the desire to be male and not female may be a trauma response.”

The quotes I bolded in the biographies above reveal young women who tried to fight their fate. After K.C. Miller realized that there was no escaping her sex, she vented in a video that went viral. As Reuters summarizes:

Miller let out years of frustration in a video posted on Twitter. She told viewers she felt she looked too masculine to detransition. She described how testosterone thinned her hair. “I don’t see me personally being able to come back from what’s happened,” she said in the video.

The video went viral, registering nearly four million views within days and igniting an avalanche of comments. Two days after Miller’s post, Alejandra Caraballo, a transgender woman, LGBTQ-rights advocate and clinical instructor at Harvard Law School’s Cyberlaw Clinic, wrote on Twitter: “The detransition grift where you complain about transitioning not making you look like a greek god but you also aren’t actually detransitioning yet because you don’t feel like your birth gender and you follow a bunch of anti-trans reactionaries that want all trans people gone.”

Caraballo told Reuters she reacted to Miller’s video because those types of detransition stories are “outlier examples being used by many on the anti-trans side to undermine access to gender-affirming care. They aren’t representative of detransitioners on the whole.”

In other posts and direct messages, some transgender people Miller had once idolized made fun of her appearance and criticized her decisions. One person made a death threat.

A few weeks later, Miller said she stopped taking testosterone, began to feel suicidal and sought psychiatric care. She uses female pronouns among friends, but still presents as a man in public.

Detransitioners are accustomed to vitriol from their former community, as when transgender comedian Diana Salameh exclaimed, “You people who jumped the gun, made wrong decisions that you should actually feel embarrassed for, but you want to blame somebody else… I think you all need to sit down and shut the fuck up!” Dr. Kinnon MacKinnon, a transgender man and professor of social work who has been researching detransition, marveled at the invective that detransitioners endure, telling Reuters, “I can’t think of any other examples where you’re not allowed to speak about your own healthcare experiences if you didn’t have a good outcome.” But the detransitioner is a type of apostate, and true believers always hate their apostates for demonstrating so vividly why there is a debate to be had.

Fortunately, the sex binary taboo has started to erode. Sullivan wrote about a turning point this past April:

When we argued that children should get counseling and support but wait until they have matured before making irreversible, life-long medical choices they have no way of fully understanding, we were told we were bigots, transphobes and haters.

The reason we were told that children couldn’t wait and mature was that they would kill themselves if they didn’t. This is one of the most malicious lies ever told in pediatric medicine. While there is a higher chance of suicide among children with gender distress than those without, it is still extremely rare. And there is absolutely no solid evidence that treatment reduces suicide rates at all.

Don’t take this from me. The most authoritative and definitive study of the question has just been published in Britain, “The Cass Report,” by Hilary Cass, one of the most respected pediatricians in the country. It’s 388 pages long, crammed with references, five years in the making, based on serious research and interviews with countless doctors, parents, scientists and, most importantly, children and trans people directly affected. In the UK, its findings have been accepted by both major parties and even some of the groups who helped pioneer and enable this experiment. I urge you to read it — if only the preliminary summary.

It’s a decisive moment in this debate. After weighing all the credible evidence and data, the report concludes that puberty blockers are not reversible and not used to “take time” to consider sex reassignment, but rather irreversible precursors for a lifetime of medication. It says that gender incongruence among kids is perfectly normal and that kids should be left alone to explore their own identities; that early social transitioning is not neutral in affecting long-term outcomes; and that there is no evidence that sex reassignment for children increases or reduces suicides.

How on earth did all the American medical authorities come to support this? The report explains that as well: all the studies that purport to show positive results are plagued by profound limitations: no control group, no randomization, no double-blind studies, no subsequent follow-up with patients, or simply poor quality. Some are arguing that the report unfairly ignored countless studies that support child transition. I’ll leave it to the editor-in-chief of the British Medical Journal to address that point:

“One emerging criticism of the Cass review is that it set the methodological bar too high for research to be included in its analysis and discarded too many studies on the basis of quality. In fact, the reality is different: studies in gender medicine fall woefully short in terms of methodological rigour; the methodological bar for gender medicine studies was set too low, generating research findings that are therefore hard to interpret.

“The methodological quality of research matters because a drug efficacy study in humans with an inappropriate or no control group is a potential breach of research ethics. Offering treatments without an adequate understanding of benefits and harms is unethical. All of this matters even more when the treatments are not trivial; puberty blockers and hormone therapies are major, life altering interventions …

“The evidence base for interventions in gender medicine is threadbare, whichever research question you wish to consider—from social transition to hormone treatment.”

Humanity’s rebellion against the immutable sex binary is premised on the hope of overcoming a most ancient reality. It is a loftier goal than colonizing Mars or sending forth an intergenerational spaceship to explore the cosmic frontier. Those ambitions are for physicists, whereas biologists must study more wicked problems. We have been sexually dimorphic for over a billion years, since the primordial era when multicellular organisms first emerged. The sex binary is far older and more central to what we are than is being human.

How do we admit to our children that we could not find a way to change something so ancient and foundational? If we fear that the truth of their fate would feel unbearable to them, then what can we say to youths who are so desperate to evade puberty that death seems preferable? They are asking a question that Albert Camus called the “one truly serious philosophical problem”:

Judging whether life is or is not worth living amounts to answering the fundamental question of philosophy. All the rest — whether or not the world has three dimensions, whether the mind has nine or twelve categories — comes afterwards. These are games; one must first answer.

Camus answers in his book The Myth of Sisyphus. He channels the stoic mindset of philosophers like Marcus Aurelius, the Roman emperor who expressed such sentiments as, “It's time you realized that you have something in you more powerful and miraculous than the things that affect you and make you dance like a puppet.” Similarly, Camus once wrote, “In the midst of winter, I found there was within me an invincible summer.” They believed in the necessity of cultivating what psychologists call an internal locus of control.

But our children, by virtue of their youth, have not had enough time to develop a large store of inner strength. It is brutal to confront Camus’s “one truly serious philosophical problem” with scant life experience. It’s as if the gods are punishing our children for the sins of their fathers — for the sex stereotypes and sexual violence that every generation inherits from their parents.

For Friedrich Nietzsche, purpose buttresses our psyches. He observed that “He who has a why to live for can bear almost any how.” This sentiment lead Nietzsche to amore fati — the love of fate.

To the ear of a distressed teenager, all of this may sound like a dressed up version of “Get over it.” Stoicism is sometimes caricatured as male chauvinism, if these ideas are cheapened by reducing them to “grow a pair” or “boys don’t cry.” But do not confuse stoicism about the sex binary with acquiescence to sexism.

Camus explains how falling in love with our fate is the only viable rebellion against the gods, and he uses the myth of Sisyphus to show us why:

As for this myth, one sees merely the whole effort of a body straining to raise the huge stone, to pull it and push it up a slope a hundred times over; one sees the face screwed up, the cheek tight against the stone, the shoulder bracing the clay-covered mass, the foot wedging it, the fresh start with arms outstretched, the wholly human security of two earth-clotted hands. At the very end of his long effort measured by skyless space and time without depth, the purpose is achieved. Then Sisyphus watches the stone rush down in a few moments toward that lower world whence he will have to push it up again toward the summit. He goes back down to the plain.

It is during that return, that pause, that Sisyphus interests me. A face that toils so close to stones is already stone itself! I see that man going back down with a heavy yet measured step toward the torment of which he will never know the end. That hour like a breathing-space which returns as surely as his suffering, that is the hour of consciousness. At each of those moments when he leaves the heights and gradually sinks toward the lairs of the gods, he is superior to his fate. He is stronger than his rock.

If this myth is tragic, that is because its hero is conscious. Where would his torture be, indeed, if at every step the hope of succeeding upheld him? The workman of today works every day in his life at the same tasks, and this fate is no less absurd. But it is tragic only at the rare moments when it becomes conscious. Sisyphus, proletarian of the gods, powerless and rebellious, knows the whole extent of his wretched condition: it is what he thinks of during his descent. The lucidity that was to constitute his torture at the same time crowns his victory. There is no fate that cannot be surmounted by scorn.

Camus was of a mind with Epictetus, the Greek slave whose stoic philosophy influenced Emperor Aurelius. He wrote the aphorism: “Circumstances don't make the man, they only reveal him to himself.” The same idea struck Viktor Frankl, the psychologist who survived Auschwitz and then wrote Man’s Search for Meaning to explain how it was possible to withstand such a fate as the Holocaust:

Is that theory true which would have us believe that man is no more than a product of many conditional and environmental factors — be they of a biological, psychological or sociological nature? Is man but an accidental product of these? Most important, do the prisoners’ reactions to the singular world of the concentration camp prove that man cannot escape the influences of his surroundings? Does man have no choice of action in the face of such circumstances?

We can answer these questions from experience as well as on principle. The experiences of camp life show that man does have a choice of action. There were enough examples, often of a heroic nature, which proved that apathy could be overcome, irritability suppressed. Man can preserve a vestige of spiritual freedom, of independence of mind, even in such terrible conditions of psychic and physical stress.

We who lived in concentration camps can remember the men who walked through the huts comforting others, giving away their last piece of bread. They may have been few in number, but they offer sufficient proof that everything can be taken from a man but one thing: the last of the human freedoms — to choose one’s attitude in any given set of circumstances, to choose one’s own way.

For Camus, choosing to bear one’s cross with dignity was the only possible revolt against fate:

I leave Sisyphus at the foot of the mountain! One always finds one’s burden again. But Sisyphus teaches the higher fidelity that negates the gods and raises rocks. He concludes that all is well. The universe henceforth without a master seems to him neither sterile nor futile. Each atom of that stone, each mineral flake of that night-filled mountain, in itself forms a world. The struggle itself toward the heights is enough to fill a man’s heart. One must imagine Sisyphus happy.

Like the concentration camp prisoner, the gods tried to take everything from Sisyphus, but one thing lay beyond their reach: his consciousness. They punished him because they wanted him to suffer — but he does not agree to suffer. Sisyphus scorned the gods by choosing happiness instead.

What, then, do we tell our children when fate treats them harshly? We should heed Camus, who believed that “crushing truths perish from being acknowledged,” and start with the truth: The sex binary is not bullshit — it is the biological bedrock upon which we evolved.

Scientists called by the defense as expert witnesses were not allowed to testify at the Scopes trial, so although Newman travelled to Dayton, Tennessee, to testify, his statement was entered into court records instead.

Though she finally discusses gamete size in this excerpt, she promptly switches back to incorrectly defining sex with chromosomes at the end of the passage.

In another prescient passage about the risks of sex binary denialism for young women, Rowling writes:

A man who intends to have no surgery and take no hormones may now secure himself a Gender Recognition Certificate and be a woman in the sight of the law. Many people aren’t aware of this.

We’re living through the most misogynistic period I’ve experienced. Back in the 80s, I imagined that my future daughters, should I have any, would have it far better than I ever did, but between the backlash against feminism and a porn-saturated online culture, I believe things have got significantly worse for girls. Never have I seen women denigrated and dehumanised to the extent they are now. From the leader of the free world’s long history of sexual assault accusations and his proud boast of ‘grabbing them by the pussy’, to the incel (‘involuntarily celibate’) movement that rages against women who won’t give them sex, to the trans activists who declare that TERFs need punching and re-educating, men across the political spectrum seem to agree: women are asking for trouble. Everywhere, women are being told to shut up and sit down, or else.

I’ve read all the arguments about femaleness not residing in the sexed body, and the assertions that biological women don’t have common experiences, and I find them, too, deeply misogynistic and regressive. It’s also clear that one of the objectives of denying the importance of sex is to erode what some seem to see as the cruelly segregationist idea of women having their own biological realities or – just as threatening – unifying realities that make them a cohesive political class. The hundreds of emails I’ve received in the last few days prove this erosion concerns many others just as much. It isn’t enough for women to be trans allies. Women must accept and admit that there is no material difference between trans women and themselves.

A few years after Rowling penned her essay, one grave consequence of conflating transwomen with women emerged in Scotland. In January 2023, Adam Graham was found guilty of two counts of rape in Glasgow, but while the rapist was awaiting trial, he announced he would begin identifying as a woman named Isla Bryson. After he was briefly detained in a woman's prison, there was an outcry over the authorities’ disregard for female inmates' safety, and then he was transferred to a male prison.

Then-First Minister Nicola Sturgeon could not navigate the controversy without tripping over the sex binary denialism taboo. In an interview that went viral, a reporter repeatedly pressed Sturgeon to answer whether she believed that trans women are women, full stop, and how that belief could be squared with ever barring trans women from female prisons. She refused to break the taboo, but her obvious discomfort with the line of questioning combined with the incoherence of her answer contributed to her stepping down from her post about a month later.

Loved this article! Cancel culture, silencing voices that speak out for the health and best interests of children in order to protect an ideology . . . under the guise of protecting children . . and so much more to think about, for all of us.

This was a depressing read as it is still unfathomable to me as to how we arrived at this place in such

a relatively short period of time and the vitriol for questioning any of it. Rather than Sisyphus I'd look to Prometheus who I decided quite early in life was punished not because fire brought heat but rather that it brought light. The penalty for seeing in darkness is to have harpies eat your liver on a daily basis. (are there now eagles who self-identify as harpies?) Taking the advice from my cereal box I'm going to let contents settle and reread at a later time.......and thank you for this.