Art in a Ghost Town

"The joy that lies incipient in decay."

In an abandoned Wyoming settlement called Shirley Basin, a small painting of voluptuous clouds has been weathering away for a few months. Sun and snow take turns trying to rub oil off the canvas, and someday the real sky will reclaim its rectangular patch on the landscape. Nineteen artists installed their creations in that site back in August, to reflect “on the eerie history and vast spaces of the American West, specifically the nuclear legacy of spaces like Shirley Basin,” by consigning their art to entropy.1

Wyoming is suffused with uranium. When America’s enthusiasm for the Atomic Age ebbed, the mining boomtowns where prospectors had extracted it deteriorated into ghost towns. Places like Shirley Basin — where the entire economy was based on uranium mining — were reduced to concrete slabs, collapsing trailers, and vehicles repurposed for target practice.2

The artists who embellished Shirley Basin participated in a centuries-old tradition of poets and painters making pilgrimages to ruins. Roger Scruton, the late philosopher of aesthetics and defender of beauty, described the purpose of such artists:

Look at any picture by one of the great landscape painters – Poussin, Guardi, Turner, Corot, Cézanne – and you will see that idea of beauty celebrated and fixed in images. Those painters do not turn a blind eye to suffering, or to the vastness and threateningness of the universe, of which we occupy so small a corner. Far from it. Landscape painters show us death and decay in the very heart of things: the light on their hills is a fading light; the walls of their houses are patched and crumbling like the stucco on the villages of Guardi. But their images point to the joy that lies incipient in decay, and to the eternal that is implied in the transient.3

But the Shirley Basin artists also inverted this tradition, when they added to the landscape rather than render it. Unlike J. M. W. Turner repeatedly returning to the remnants of Heidelberg Castle to sketch the collapsed towers from every angle, they did not visit Shirley Basin to transcribe its majesty — for there is none. That ghost town is contaminated more by ugliness than uranium.

Can you imagine the fallout if artists decided that Heidelberger Schloss needed sprucing up, and installed their artwork to add interest to the ruins? The Germans might throw them in prison.4

Even the plumbing was a thing of beauty in bygone eras.5 But by the time Shirley Basin sprung up in 1960, architects had for some time been enthralled with stern designs by Le Corbusier, the pioneer of modern architecture who disdained decoration and color as “suited to simple races, peasants, and savages.”6 This is not to say that Shirley Basin was designed by highfalutin architects — surely not — but rather to set the scene of a culture that largely turned away from classical beauty.7 In 1960 Wyoming, the plumbing was not beautiful.

Western boomtowns of the previous century were built just as hastily as their Atomic Age descendants, but their false front façades held some charm. These iconic Old West constructions had front walls that rose high above their buildings’ roofs to project a grandeur that the back of the buildings could not substantiate. They were humble structures, but their façades puffed out their chests and stood up tall. Their parapets were adorned with molded cornices, and the fancier storefronts hid simple wooden frames behind a face of brick or stone. False front façades helped define the aesthetic of the Wild West.

While Shirley Basin lacks the charisma of 19th century boomtowns, it is a psychological curiosity. Stray equipment and dusty metal racks hint at the fearsome power harnessed by the nuclear era, though this allusion would only occur to visitors who know of its history. The appeal is as invisible as radiation.

And so, a group of artists took it upon themselves to materialize that covert allure and try to make the ruins of Shirley Basin a place worth visiting. They partook in what Scruton called “the joy that lies incipient in decay” by celebrating a remote and overlooked wasteland.8 For their artwork, “decay” carries additional layers of meaning; those who travel to this art installation may wonder whether radioactive decay bombards them as they view artwork meant to erode.

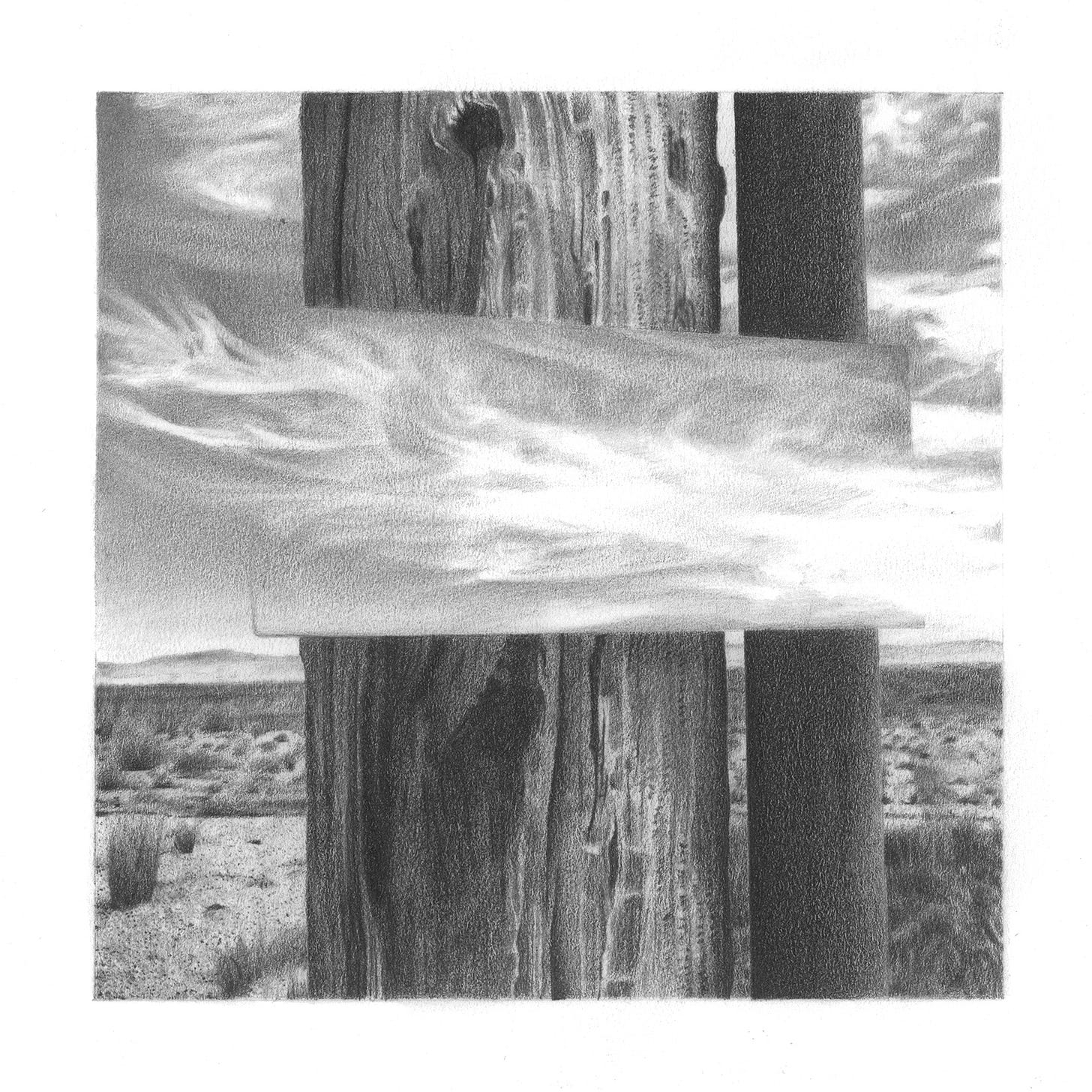

This artwork also points “to the eternal that is implied in the transient.” As real clouds shape shift behind that small painting, its fluffy features remain frozen. At least, until the wind reduces the canvas to a tattered flag.

Until then, it is a small point of beauty within the blight. Until then, the ruins of Shirley Basin have some romance.

This permanent exhibition, which is “free and open to the public willing to take the pilgrimage,” is titled ReActivate and includes artists from the Hyperlink and Land Report art collectives. The small painting is “Atmosphere No 81 (Bridges),” 2023, by Ian Fisher. You can learn more here.

To tie their artwork into these themes of radioactive and erosive decay, the artists write that they have “ensured that their work will ‘glow’ as a way to unify the works in the show and set these objects apart from the decaying ruins they are exhibited amongst. Another thoughtful facet to the works selected for the show is that they were once incomplete and abandoned projects that the artists re-activated for this project.”

Scruton, Roger. Beauty: A Very Short Introduction (New York: Oxford University Press Inc., 2009), 146.

Germans take rules very seriously.

See: Roman aqueducts, Indian stepwells, and the Basilica Cistern in Istanbul.

Le Corbusier. Towards a New Architecture (Hawthorne, California: BN Publishing, 1923), 143.

Americans tore down many of their architectural wonders between 1950-1970, most damningly the old Penn Station in New York City, which was demolished in 1968 to make room for the eyesore deceptively named Madison Square Garden.

Thinking of wastelands, I’m reminded of T. S. Eliot’s famous poem by that name. (J. Robert Oppenheimer, the father of the atomic bomb, loved The Waste Land.) In it, a veteran encounters the ghost of a fallen comrade and asks him a question:

‘That corpse you planted last year in your garden,

‘Has it begun to sprout? Will it bloom this year?

‘Or has the sudden frost disturbed its bed?

Because the artists explain that they chose “once incomplete and abandoned projects” to install in Shirley Basin, these lines of the poem come to mind. Did the reanimated corpses of their artwork bloom in that ugly ruin?