Art Worth Dying For

Have people ever risked their lives for ugly art?

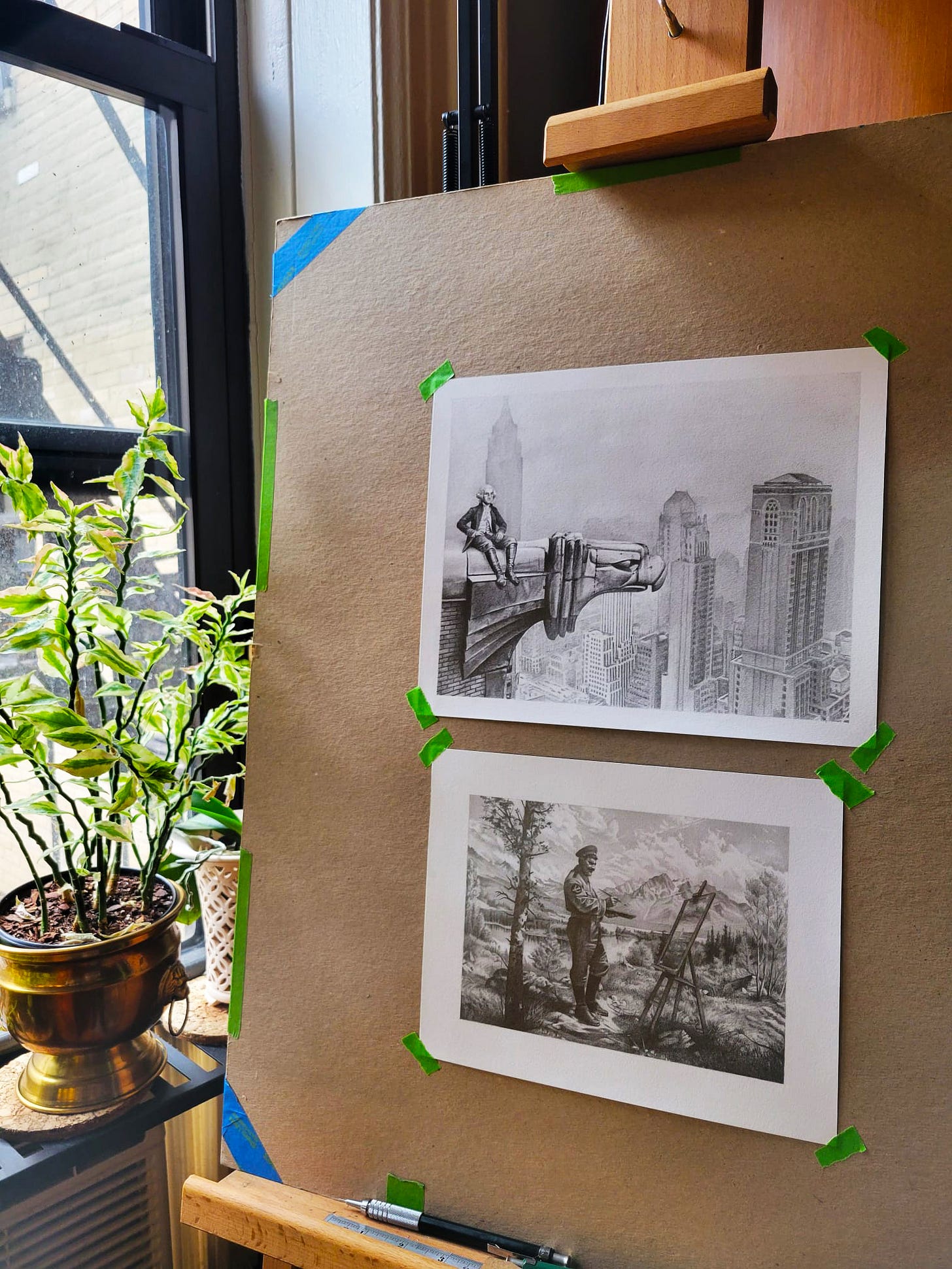

Lately I’ve been writing about the moment when artists turned away from beauty — this was one of the great tragedies of the 20th century. Two weeks ago, I published “‘America was supposed to be Art Deco’” here on Fashionably Late Takes, which is about this problem in architecture; my latest Quillette essay, which came out on Friday, is on the anti-beauty stance in painting and sculpture. I conceive of these as a diptych, because my argument in each is bolstered by the other, and I drew complimentary pseudo-historical scenes for both visual essays.

This is an addendum to my diptych, and to my latest Quillette piece in particular: “The Totalitarian Artist: Politics vs Beauty.” Please give that a read! Consider this a coda, as it were, to my argument there: Art should be beautiful.

While working on these essays, I began to wonder: Have people ever risked their lives for ugly art?

It is a remarkable testament to the importance of art that anyone has ever valued it above a human life, especially their own. Some of these stories have been popularized, as in George Clooney's (rather cheesy) 2014 film The Monuments Men about the brave individuals who risked or lost their lives to safeguard artwork from Nazi plundering and purging. Some such historical sacrifices might have been fueled by religious belief — how did Michelangelo's art survive the 1527 sacking of Rome? — but I suspect that for anyone who risks it all to save an artwork, a key motivation is safeguarding irreplaceable beauty.

And yet, the art world has devalued beauty over the past century. Take, for example, the philosopher of aesthetics Arthur Danto admitting to feeling “sheepish about writing on beauty" in his 2003 book The Abuse of Beauty, because it “had almost entirely disappeared from artistic reality in the twentieth century, as if attractiveness was somehow a stigma, with its crass commercial implications.” Here we have a 21st century philosopher of aesthetics who worried that he would suffer derision for taking beauty seriously.

Nothing reveals our values more than putting skin in the game. It is unsurprising to me that some people value beautiful art enough to stake their lives on protecting it. Take it from Viktor Frankl, who after surviving Auschwitz had this to say about beauty:

Should I perhaps try to explain for you with some hackneyed phrase how and why experiencing beauty can make life meaningful? I prefer to confine myself to the following thought experiment: imagine that you are sitting in a concert hall and listening to your favorite symphony, and your favorite bars of the symphony resound in your ears, and you are so moved by the music that it sends shivers down your spine; and now imagine that it would be possible (something that is psychologically so impossible) for someone to ask you in this moment whether your life has meaning. I believe you would agree with me if I declared that in this case you would only be able to give one answer, and it would go something like: “It would have been worth it to have lived for this moment alone!”

If experiencing beauty can make life worth living — even a tragic life beset by suffering, as Frankl experienced to the extreme — then the idea of risking one's life to save beautiful art is comprehensible. It is harder for me to imagine people sacrificing themselves to protect ugliness. And given that artists only began making ugly things in the 20th century, perhaps no one has had a chance to test my intuition that someone would not risk their life for ugly art unless they were possessed by some sinister ideology.

But it is nearly impossible to discuss aesthetic judgments without someone piping up to parrot the popular opinion that beauty is neither objective nor universal — that beauty is “in the eye of the beholder” — a notion that, if true, would mean there could be no real distinction between the beautiful and the ugly. True to form, a pedant promptly showed up in the comment section for “The Totalitarian Artist” to inform me that, “Beauty, or rather the assessment of which objects are beautiful, is almost fully provisional, based on the influence of prevailing culture and personal inclination.” Because this sentiment is woefully widespread, it’s worth taking a moment to dispute it.

The trendy conflation of beauty with taste flatters human arrogance, as if we are not animals with evolved sensibilities common to our species. Of course some people prefer Kyoto to Paris, but it would be weird for someone to go so far as to declare that Paris is an ugly city — literally weird, meaning it happens so rarely that we should express skepticism towards anyone who would say that, and wonder if such a person is a contrarian or psychologically damaged. That preferences exist for different types of beauty does not negate its universality any more than preferences for cheesecake versus baklava negates the universal human craving for sugar, along with the biological reasons for why we evolved our sweet tooth.

This nonsense is part of the blank slate doctrine that there is no biologically ingrained human nature, and therefore human minds are so malleable that enculturation corners the market on explaining our behavior. When cognitive scientist Steven Pinker debunked the idea that we are born tabula rasa in his 2002 book The Blank Slate: The modern denial of human nature, the second-most controversial chapter was about the arts, in which he writes that, “The dominant theories of elite art and criticism in the twentieth century grew out of a militant denial of human nature. One legacy is ugly, baffling, and insulting art. The other is pretentious and unintelligible scholarship.” Pinker describes the 20th century impoverishment of the arts that I discuss at length in ‘“America was supposed to be Art Deco’” and “The Totalitarian Artist”:

Modernism certainly proceeded as if human nature had changed. All the tricks that artists had used for millennia to please the human palate were cast aside. In painting, realistic depiction gave way to freakish distortions of shape and color and then to abstract grids, shapes, dribbles, splashes, and, in the $200,000 painting featured in the recent comedy Art, a blank white canvas. In literature, omniscient narration, structured plots, the orderly introduction of characters, and general readability were replaced by a stream of consciousness, events presented out of order, baffling characters and causal sequences, subjective and disjointed narration, and difficult prose. In poetry, the use of rhyme, meter, verse structure, and clarity were frequently abandoned. In music, conventional rhythm and melody were set aside in favor of atonal, serial, dissonant, and twelve-tone compositions. In architecture, ornamentation, human scale, garden space, and traditional craftsmanship went out the window (or would have if the windows could have been opened), and buildings were “machines for living” made of industrial materials in boxy shapes. Modernist architecture culminated both in the glass-and-steel towers of multinational corporations and in the dreary high-rises of American housing projects, postwar British council flats, and Soviet apartment blocks.

…

Beginning in the 1970s, the mission of modernism was extended by the set of styles and philosophies called postmodernism. Postmodernism was even more aggressively relativistic, insisting that there are many perspectives on the world, none of them privileged. It denied even more vehemently the possibility of meaning, knowledge, progress, and shared cultural values. It was more Marxist and far more paranoid, asserting that claims to truth and progress were tactics of political domination which privileged the interests of straight white males. According to the doctrine, mass-produced commodities and media-disseminated images and stories were designed to make authentic experience impossible.

Then Pinker zeroes in on how denying human nature undermines our ability to understand what art is:

Ultimately what draws us to a work of art is not just the sensory experience of the medium but its emotional content and insight into the human condition. And these tap into the timeless tragedies of our biological predicament: our mortality, our finite knowledge and wisdom, the differences among us, and our conflicts of interest with friends, neighbors, relatives, and lovers. All are topics of the sciences of human nature.

Fortunately, some philosophers of aesthetics are unembarrassed to take beauty seriously. In the year before his death in 2010, Dennis Dutton contributed a crucial corrective to the chic misconception that beauty is mostly subjective in The Art Instinct: Beauty, Pleasure, and Human Evolution. In his subsequent TED talk, Dutton summarized his argument in just fifteen minutes — which both TED and NPR described as “provocative,” but which I would characterize as “sensible.” For anyone who reads my essays on beauty and balks at my claiming there is an objective difference between the beautiful and the ugly, I want to share an extended excerpt from Dutton's talk:

Now this is an extremely complicated subject, in part because the things that we call beautiful are so different. I mean, just think of the sheer variety: a baby's face, Berlioz's “Harold in Italy,” movies like The Wizard of Oz, or the plays of Chekhov, a central California landscape, a Hokusai view of Mt. Fuji, “Der Rosenkavalier,” a stunning match-winning goal in a World Cup soccer match, Van Gogh's “Starry Night,” a Jane Austen novel, Fred Astaire dancing across the screen. This brief list includes human beings, natural landforms, works of art, and skilled human actions. An account that explains the presence of beauty in everything on this list is not going to be easy. I can, however, give you at least a taste of what I regard as the most powerful theory of beauty we yet have. And we get it not from a philosopher of art, not from a Postmodern art theorist, or a bigwig art critic. No. This theory comes from an expert on barnacles and worms and pigeon breeding. And you know who I mean: Charles Darwin.

Of course, a lot of people think they already know the proper answer to the question, “What is beauty?” It's in the eye of the beholder, it's in what moves you personally, or as some people — especially academics — prefer, beauty is in the culturally conditioned eye of the beholder. People agree that paintings or movies or music are beautiful, because their cultures determine a uniformity of aesthetic taste. Taste for both natural beauty and for the arts travel across cultures with great ease. Beethoven is adored in Japan. Peruvians love Japanese wood block prints. Inca sculptures are regarded as treasures in British museums, while Shakespeare is translated into every major language of the Earth. Or just think about American jazz or American movies — they go everywhere. There are many differences among the arts, but there are also universal, cross-cultural aesthetic pleasures and values. How can we explain this universality?

The best answer lies in trying to reconstruct a Darwinian evolutionary history of our artistic and aesthetic tastes. We need to reverse engineer our present artistic tastes and preferences, and explain how they came to be engraved in our minds by the actions of both our prehistoric, largely Pleistocene environments, where we became fully human, but also by the social situations in which we evolved. This reverse engineering can also enlist help from the human record preserved in prehistory. I mean fossils, cave paintings, and so forth. And it should take into account what we know of the aesthetic interests of isolated hunter-gatherer bands that survived into the 19th and 20th centuries.

Now I personally have no doubt whatsoever that the experience of beauty, with its emotional intensity and pleasure, belongs to our evolved human psychology. The experience of beauty is one component in a whole series of Darwinian adaptations. Beauty is an adaptive effect, which we extend and intensify in the creation and enjoyment of works of art and entertainment.

Dutton then details how beauty is adaptive for human survival, explaining that it’s involved in human sexual selection, status games, and identifying a fertile or safe landscape. His examples come from the study of human prehistory and our animal cousins, who also share our sense of beauty to some degree. But lest this sound too cold, as if scientists were dissecting beauty on a chilly, steel examination table, consider that in 1977, while Carl Sagan was launching the Voyager Golden Records into outer space to share humanity’s artistic achievements with the universe, one of our most celebrated living artists, Marina Abramović, performed Expansion in Space with her partner ULAY, in which they ran into walls naked.

No wonder Richard Feynman argued with artists, although at least he was friends with one who still believed in beauty:

He would hold up a flower and say, “Look how beautiful it is,” and I would agree. And he says, “You see, I as an artist can see how beautiful this is, but you as a scientist take this all apart and it becomes a dull thing.” And I think that he’s kind of nutty . . . I see much more about the flower than he sees. I can imagine the cells in there, the complicated actions inside, which also have a beauty. I mean, it’s not just beauty at this dimension of one centimeter, there’s also beauty at smaller dimensions: the inner structure, also the processes. The fact that the colors of the flower evolved in order to attract insects to pollinate it is interesting. It means that insects can see the color. It adds a question: does this aesthetic sense also exist in lower forms? Why is it aesthetic? All kinds of interesting questions, which the science, knowledge, only adds to the excitement, mystery, and awe of a flower. It only adds. I don’t understand how it subtracts.

We are lucky that 20th century scientists did not abandon beauty along with the artists. They gave Dutton the tools to reassert its necessity to humanity. Dutton concludes:

For us moderns, virtuoso technique is used to create imaginary worlds in fiction and in movies, to express intense emotions with music, painting, and dance. But still, one fundamental trait of the ancestral personality persists in our aesthetic cravings: the beauty we find in skilled performances. From Lascaux to the Louvre to Carnegie Hall, human beings have a permanent, innate taste for virtuoso displays in the arts. We find beauty in something done well.

…

Is beauty in the eye of the beholder? No! It's deep in our minds, it's a gift handed down from the intelligent skills and rich emotional lives of our most ancient ancestors. Our powerful reaction to images, to the expression of emotion in art, to the beauty of music, to the night sky, will be with us and our descendants for as long as the human race exists.

So when I wonder whether anyone has died for ugly art, the answer is not confined to either my personal taste or yours. Even the 20th century aesthetic ingrates who rejected beauty sometimes treated it like a real thing, as when the abstract painter Barnett Newman declared that “the impulse of modern art” was “the desire to destroy beauty.”1 As for myself, when it comes to paintings, I would give my life for Van Gogh’s Starry Night, but never for a canvas by Barnett Newman.

In Newman’s defense, he expressed admiration for the sublime at the same time that he denigrated beauty, though I would argue that he also misunderstood the sublime… perhaps in a future essay. In any case, I agree with Newman that his paintings are ugly.

In 1926, the renowned American social critic H.L. Menchen wrote a famously acerbic essay The Libido for the Ugly in which he wonders if there “is something that the psychologists have so far neglected: the love of ugliness for its own sake”..... ask yourself this question: how many people if shown – say - Vermeer’s Girl with a Pearl Earring would think it a great work of art even if they didn’t know it was famous and valuable? And now ask yourself (hypothetically of course) how many would think that about Picasso’s Les Demoiselles d'Avignon if they’d somehow never seen – or even heard of - Cubism or any other type of abstract painting? And now ask yourself if you would know that Mondrian’s Composition with Red Blue and Yellow - is a great work of art if no one had ever told you so? https://grahamcunningham.substack.com/p/deconstructing-deconstructivism

The history of Art and Culture in the modern age is the story of a palace coup orchestrated by the eunuchs in a harem, the eunuchs being "theorists" and "critics" who replaced beauty, craft, and rigor with stilted verbiage and pseudoradical jargon, where the artist, the viewer and the work are supplanted by whatever social and political theories can be added like handles for easier carrying (and where the incentives somehow always magically align w the personal and career needs of the theorist class).

Once Art could be anything it became nothing, and once being an artist didn't involve talent, skill, technique etc it meant anyone could be an "artist", which explains such 21st-century masterpieces as the guy who canned his own shit or the female "artists" who consider exposing their unmade beds or breasts and genitals "art".

Once Art became about theories, causes, interpretations, social and political positioning, once every artwork came with a long explanation larded with guild jargon, its inevitable end was to be another luxury good or academic franchise where a priesthood of theorists play their status games while pretending it's all about "Progress" "inclusion" "Equality" or whatever else is the trendy slogan du jour.

Our theorist class are the termites of civilization, chewing to pieces and getting fat by destroying all they could never create. I'm not so sure "artists turned away from beauty" as much as they were bullied away from it, as the theorist class are masters of punitive moralism and personal denunciation.

Great piece! Cheers!