Curiosity is Sacred

Part 1

An earlier version of this essay first appeared in Areo Magazine on March 3, 2019. Here it is adapted as a visual essay.

The second installment in this two-part visual essay can be read here.

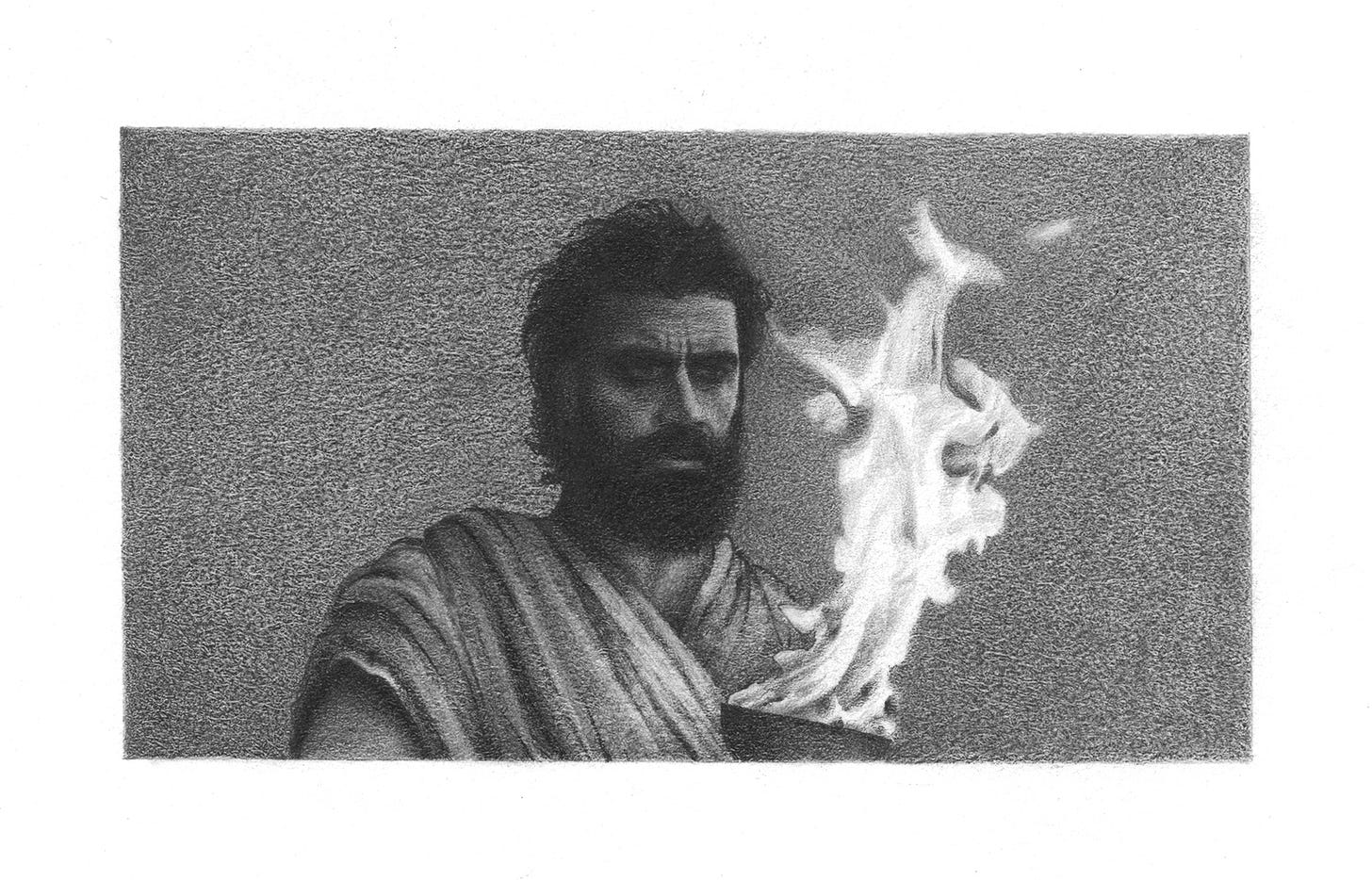

The pursuit of knowledge frightens humanity. Many stories warn us that curiosity can kill the cat. God banished Adam and Eve from the Garden of Eden because they ate of the Tree of Knowledge of Good and Evil. In the Faust legend, a man sold his soul to the devil in exchange for unlimited knowledge. My personal favorite is the Greek myth of Prometheus, the titan who sculpted humanity out of clay.

Prometheus wanted his creation to thrive with the gift of fire. Fire symbolizes enlightenment, which literally means “into the light.” It also enables progress, and the implications of harnessing fire help distinguish man from beast.

But Zeus forbade this. Undeterred, Prometheus stole fire from the gods at Mount Olympus. When Zeus found out, he punished both gift giver and receiver. Zeus condemned Prometheus to eternal torture and gave the first woman, Pandora, both a jar and a curious disposition.

Pandora opened the jar to find out what it contained, and all manner of horror and evil rushed out. Aghast, she shut it tight — too late. All that she managed to trap inside was hope.

And yet, I argue that curiosity is sacred.

Curiosity is the yearning to understand. It motivates the pursuit of knowledge, as each answered question uncovers new mysteries that urge us to wander further into the unknown. When this drive is focused and codified, we call it science, the Latin word for knowledge. Curiosity is characterized by a dogged desire for truth — even ugly truths. Falsehoods cannot satisfy the yearning to understand.

To understand the truth, we must attempt to prove our ideas wrong over and over again. We can feel some confidence in our ideas only after we exhaust our ability to disprove them. This method is simple yet revolutionary, because human nature makes us far more talented at proving ourselves right than wrong.

The counterintuitive conviction to break our ideas is central to science. We inevitably fall short, because our ideas are too precious to us, but other people who do not cherish them will interrogate our ideas better. This results in a body of knowledge that enables us to perform miracles: we are fleshy and featherless yet we have learned to fly.

But is there something to all those stories that warn humanity about curiosity?

The Prometheus myth bears an uncanny resemblance to the discovery of nuclear power, as if scientists tried to steal fire from the nuclear furnace that is our sun. It is but a small poetic flourish to describe nuclear physicists as Promethean figures, as J. Robert Oppenheimer's biographers have done.

At the dawn of the Atomic Age, many believed radiation was a panacea and celebrated nuclear power as the fuel of an increasingly utopian civilization. Like Prometheus, they wanted to use that fire to promote progress. But after World War II, most came to believe that atomic energy is coupled with Pandora's jar. It unleashed all manner of horror and evil, holding hope hostage with the threat of mutually assured destruction. Susan Sontag described:

…the trauma suffered by everyone in the middle of the 20th century when it became clear that from now on to the end of human history, every person would spend his individual life not only under the threat of individual death, which is certain, but of something almost unsupportable psychologically — collective incineration and extinction which could come any time, virtually without warning.

Scientists are professionally curious. Their ability to invent existential threats seems to justify ancient fears about the pursuit of knowledge, because learning how the world works is meaningless if we annihilate ourselves. So storytellers amended the old myths, as in Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus and in much science fiction, from Isaac Asimov’s I, Robot to HBO’s Westworld. When specific anxieties about science shift, the stories shift with them, the way Spider-Man was bitten by a radioactive spider in 1962, but by 2000 the spider was instead genetically modified. Throughout the generations, these stories have warned us about hubris, and taught us, as Peter Parker learned from his Uncle Ben’s death, that with great power comes great responsibility.

In his 1955 speech to the National Academy of Sciences titled “The Value of Science,” Richard Feynman used a Buddhist proverb to elucidate the blind nature of science:

To every man is given the key to the gates of heaven; the same key opens the gates of hell.

Of course it is wise to caution against unleashing hell, but if we throw away the key, then we cannot get into heaven.

Feynman, who helped invent the bomb, insists that science is nevertheless worthwhile:

Scientific knowledge is a body of statements of varying degrees of certainty — some most unsure, some nearly sure, none absolutely certain. Now, we scientists are used to this, and we take it for granted that it is perfectly consistent to be unsure — that it is possible to live and not know. But I don’t know whether everyone realizes that this is true. Our freedom to doubt was born of a struggle against authority in the early days of science. It was a very deep and strong struggle. Permit us to question— to doubt, that’s all — not to be sure. And I think it is important that we do not forget the importance of this struggle and thus perhaps lose what we have gained. Here lies a responsibility to society.

We can learn humility from science if it ennobles us to admit what we do not know. Doubting ourselves is unpalatable, but the great pleasure of satisfying curiosity can help us overcome the distaste.

This conviction to doubt rather than cling to our ideas inspired the great philosopher of science Karl Popper, who identified falsifiability as paramount to the pursuit of knowledge. Falsifiability is the capacity for an idea to be wrong. Popper insisted that the measure of an idea's value is how well it withstands our efforts to break it.

Of course, not everyone learns humility from pursuing knowledge. Or like Dr. Frankenstein, they learn to fear hubris too late, only after creating a monster hell-bent on murder. For every superhero with a radioactive backstory or a high tech science lab, there is a villain with the same advantages. A classic of this genre is Satan in Milton’s Paradise Lost, the fallen angel who worshiped his own intellect before God. And — lest we comfort ourselves by dismissing these examples as fiction — remember that the French Revolutionaries who decapitated around 40,000 people during their Reign of Terror turned Notre Dame into a Temple of Reason.

But, on balance, the pursuit of knowledge has done more good than harm. Feynman’s entreaty is supported by Steven Pinker’s tome Enlightenment Now, where Pinker writes that his favorite sentence comes from a Wikipedia entry:

Smallpox was an infectious disease caused by either of two virus variants, Variola major and Variola minor.

Pinker explains:

Yes, “smallpox was.” The disease that got its name from the painful pustules that cover the victim’s skin, mouth, and eyes and that killed more than 300 million people in the 20th century has ceased to exist.

He discusses this miracle on page 64 of a nearly 600-page “case for reason, science, humanism, and progress.” (The subtitle of the book.) The voluminous information he compiled in Enlightenment Now demonstrates how invaluable science has been to human flourishing. Science-driven advancements have saved hundreds of millions of lives.

In the Promethean myth, the titan was willing to risk Zeus’s wrath because his punishment could not outweigh the gift of fire — of enlightenment.

The quantifiable value of science should not be understated. Pinker concluded that it “has granted us the gifts of life, health, wealth, knowledge, and freedom,” and that “the spirit of science is the spirit of the Enlightenment.” Even more fundamentally, this is the spirit of curiosity.

Feynman describes curiosity as a “religious experience,” expressing the feeling in a poem as:

…atoms with consciousness; matter with curiosity.

Stands at the sea, wonders at wondering: I, a universe of atoms, an atom in the universe.

He continues:

The same thrill, the same awe and mystery, comes again and again when we look at any question deeply enough. With more knowledge comes a deeper, more wonderful mystery, luring one on to penetrate deeper still. Never concerned that the answer may prove disappointing, with pleasure and confidence we turn over each new stone to find unimagined strangeness leading on to more wonderful questions and mysteries — certainly a grand adventure!

This joy is its own reward. It counteracts the typical aversion to ugly truths, easing the discomfort we feel when the truth hurts, as the thrill of exploration overwhelms the pain. Eager to experience that thrill again, curious minds begin to crave truth. Without it, they cannot satisfy the yearning to understand. Curiosity does not seek truth because it is the moral choice, but because it is the pleasurable choice.

Perhaps progress was more or less an accident, a byproduct of inumerable people exploring their individual interests throughout the millennia. If so, uncovering truth is an emergent property of humanity’s curiosity. Though a single brilliant mind will struggle to challenge precious ideas, as curious people interact, they confront each other’s oversights and biases until the truth emerges from their debates. And then humanity can apply the resulting knowledge to solving problems, propelling progress forward with ideas like the germ theory of disease and inventions like the smallpox vaccine.

To anyone who values truth and progress, curiosity is sacred.

Sacred values hold society together. Moral psychologist Jonathan Haidt compares sanctity to a maypole dance in The Righteous Mind:

As the men and women pass each other and swerve in and out, their ribbons weave a kind of tubular cloth around the pole. The dance symbolically enacts the central miracle of social life: e pluribus unum.

Haidt theorizes that sanctity evolved to foster cooperation and that sacred values are indispensable to social cohesion. Given this insight, we should bind society together with the yearning to understand.

If curiosity is sacred, then its associated qualities — falsifiability and uncertainty — are moral imperatives. Speaking sixty years before the publication of Enlightenment Now, Feynman’s urgency expressed his fear of losing the kind of progress Pinker charted unless we honor those moral imperatives. Like Pinker, Feynman bundles reason, science, humanism, and progress together:

What can we say to dispel the mystery of existence? If we take everything into account — not only what the ancients knew, but all of what we know today that they didn’t know — then I think we must frankly admit that we do not know.

But, in admitting this, we have probably found the open channel. This is not a new idea; this is the idea of the age of reason. This is the philosophy that guided the men who made the democracy that we live under. The idea that no one really knew how to run a government led to the idea that we should arrange a system by which new ideas could be developed, tried out, and tossed out if necessary, with more new ideas brought in — a trial-and-error system. This method was a result of the fact that science was already showing itself to be a successful venture at the end of the eighteenth century.

Even then it was clear to socially minded people that the openness of possibilities was an opportunity, and that doubt and discussion were essential to progress into the unknown. If we want to solve a problem that we have never solved before, we must leave the door to the unknown ajar.

Understood this way, curiosity should be sacred — at least to societies that value liberal democracy, because it is part of their ethos. Aspiring to problem solve by breaking our ideas is how liberal democracies course correct while navigating disparate interests in a diverse society. The truth provides a common ground among disparate interests. And by desiring honest explanations of how the world works, we expand this common ground. Curiosity can bind society together.

It is no small matter to make something sacred. We must account for the misgivings voiced in stories like Frankenstein and Faust, and justify curiosity’s pursuit of pleasure. An elegant framework for this undertaking comes from Thomas Sowell’s A Conflict of Visions:

[A vision] is what we sense or feel before we have constructed any systematic reasoning that could be called a theory, much less deduced any specific consequences as hypotheses to be tested against evidence. A vision is our sense of how the world works. For example, primitive man’s sense of why leaves move may have been that some spirit moves them … Newton had a very different vision of how the world works and Einstein still another…

Visions are the foundations on which theories are built. The final structure depends not only on the foundation, but also on how carefully and consistently the framework of theory is constructed and how well buttressed it is with hard facts. Visions are very subjective, but well-constructed theories have clear implications, and facts can test and measure their objective validity. The world learned at Hiroshima that Einstein’s vision of physics was not just Einstein’s vision.

Sowell identified two overarching visions that touch human thought: the constrained and the unconstrained. The constrained vision thinks that every solution creates new problems that must be solved in turn. It expects improvements to come with trade-offs, and recognizes that expectations to the contrary make the perfect the enemy of the good.

Conversely, the unconstrained vision abhors trade-offs, which it views as defeatism. It instead demands solutions that fix problems once and for all. The unconstrained vision holds that humanity is malleable and perfectible, to the horror of the constrained vision that believes Immanuel Kant’s admonition that, “Out of the crooked timber of humanity, no straight thing was ever made":

Prudence—the careful weighing of trade-offs—is seen in very different terms within the constrained and the unconstrained visions. In the constrained vision, where trade-offs are all that we can hope for, prudence is among the highest duties. Edmund Burke called it “the first of all virtues.” “Nothing is good,” Burke said, “but in proportion, and with reference”—in short, as a trade-off. By contrast, in the unconstrained vision, where moral improvement has no fixed limit, prudence is of a lower order of importance. [William] Godwin had little use for “those moralists … who think only of stimulating men to good deeds by considerations of frigid prudence and mercenary self-interests,” instead of seeking to stimulate the “generous and magnanimous sentiment of our natures.”

The unconstrained vision may find curiosity revolting for desiring the pleasurable choice rather than the moral choice. Even if it results in something as edifying as the truth, it is tainted by selfishness. To the unconstrained vision, the real task at hand is perfecting human motives, not circumventing them.

Indeed, Feynman’s conception of science is intolerable to the unconstrained vision. Only a fiend risks unlocking the gates to hell. But if we want progress, how do we contend with the risks? Asking this question assumes a constrained vision. Avoiding this question is irresponsible.

One great risk of making curiosity sacred is that we may mistake that aim for worshipping reason. Curiosity is distinct from reason, and differentiating them helps clarify what it means to sacralize curiosity.

Feynman identifies this problem in the scientific enterprise:

Scientific knowledge is an enabling power to do either good or bad — but it does not carry instructions on how to use it. Such power has evident value — even though the power may be negated by what one does with it.

Lacking clear instructions on how to use knowledge, our passions take charge. Hence David Hume’s insight that reason is and only ought to be the slave of the passions. Most reasoning is motivated reasoning.

Anger finds reasons to hate someone; jealousy finds reasons to spite someone; empathy finds reasons to help someone; love finds reasons to marry someone you've only known for a few months. Many passions use reason to avoid the truth (you should probably get to know him better first), but for curiosity, honesty is a prerequisite for satisfying the yearning to understand. Curiosity is the passion that finds reasons to explain how things actually are.

When reason is sacred, its worshippers become arrogant, as we see in Paradise Lost and in the French Revolution. By placing so much value on intellect, the mind falls in love with itself. Unlike curiosity, reason has nothing to do with the desire to be correct; rather, we typically use reason to feel correct. An extreme form of this failing gives rise to the conspiracy theorist, who delights in fitting together perfect puzzles of subterfuge, finding every reason to justify cynical conclusions.

Sacralizing curiosity may backslide into worshipping reason. Being right is much harder than feeling right, because it requires that we are open to being wrong so that we may correct our conclusions. And although curiosity soothes the burn of being wrong, it offers incomplete protection.

Wandering into the unknown can be exhausting and even dangerous. Uncertainty generates anxiety. It is more psychologically taxing to wonder What if I’m wrong? than to reassure oneself with all the reasons why one is right.

Yet this risk of backsliding into worshipping reason is a necessary trade-off, because the alternative is worse. Without curiosity as a salve to make doubt more bearable, we may never doubt enough. Feynman admonishes:

Our responsibility is to do what we can, learn what we can, improve the solutions and pass them on… In the impetuous youth of humanity, we can make grave errors that can stunt our growth for a long time. This we will do if we say we have the answers now, so young and ignorant; if we suppress all discussion, all criticism, saying, “This is it, boys, man is saved!” and thus doom man for a long time to the chains of authority, confined to the limits of our present imagination. It has been done so many times before.

It is our responsibility as scientists, knowing the great progress and great value of a satisfactory philosophy of ignorance, the great progress that is the fruit of freedom of thought, to proclaim the value of this freedom, to teach how doubt is not to be feared but welcomed and discussed, and to demand this freedom as our duty to all coming generations.

But Feynman spoke too narrowly, because this responsibility extends beyond the scientific community. We all share in this duty. Cementing curiosity within our cultural ethic gives us enough tenacity to demand the freedom to doubt.

Imagine Prometheus descending Mt. Olympus with grim determination. He knows that his gift of fire comes with tragic trade-offs, but that the responsibility of grappling with those risks is a fair price for progress. We should embrace his attitude, because despite the danger, curiosity is sacred.

Very interesting topic!

Absolutely enlightening. It’s lengthy but I read it all.

Thank you for the share.