On Addison Del Mastro's “Who Needs a Car?”

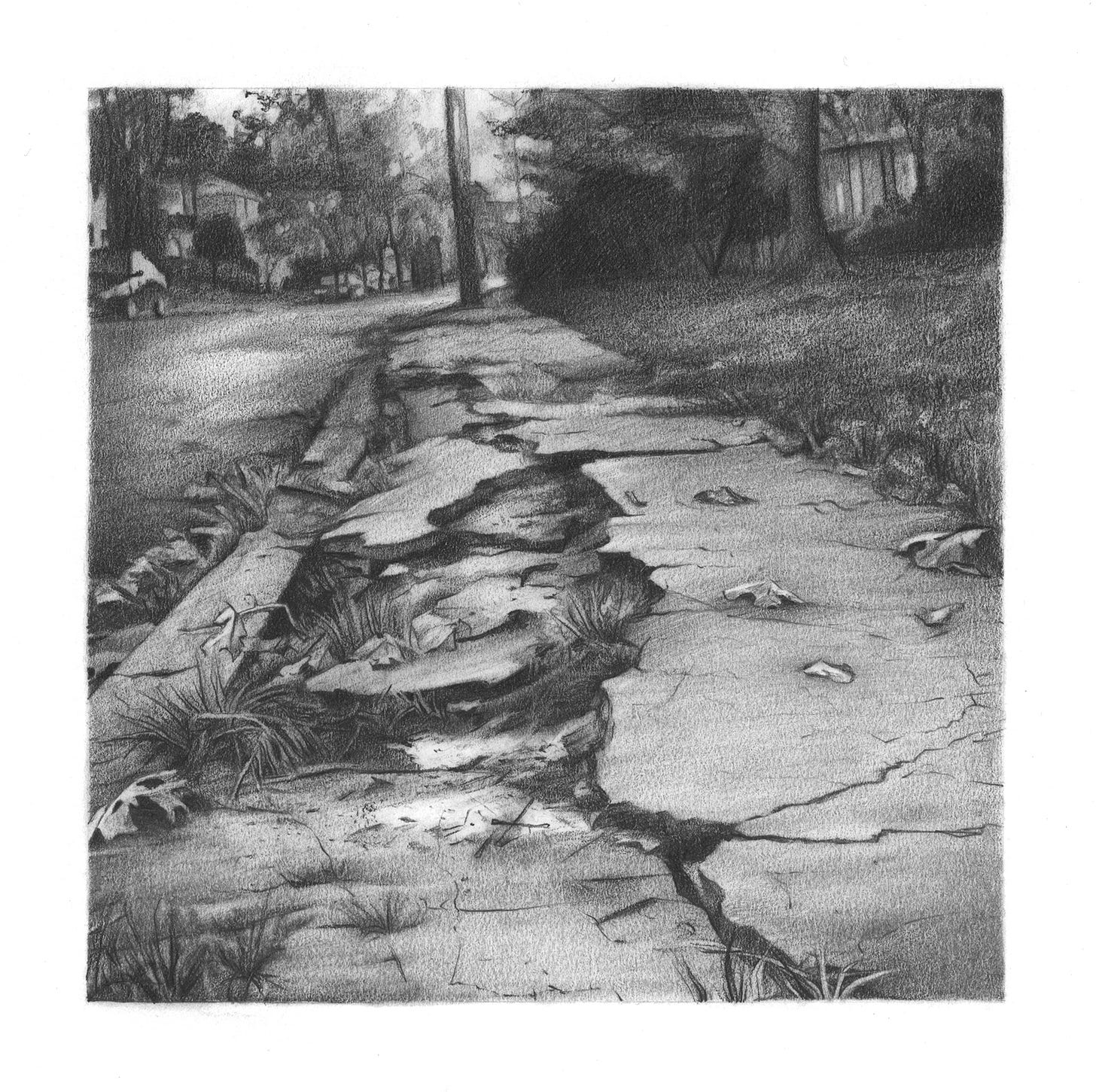

An idea worth drawing for.

This visual essay is a tribute to Addison Del Mastro. It’s part of an ongoing series called Ideas Worth Drawing For, in which I make hand-drawn images to honor the excellence of essayists I admire.

Last month, a decades-long effort to reduce car traffic in the only truly walkable American metropolis collapsed, when Governor Kathy Hochul chickened out mere weeks before the new program would have begun. Congestion pricing was too bold for the politician, despite its encouraging success in cities like Singapore and Stockholm. This latest triumph of the automobile lends credence to Addison Del Mastro's grim conclusion that “it's too late to turn back" from the ways cars have “effectively rendered the traditional city obsolete.”

New Yorkers will not be deterred from walking, but across much of the nation, the narrow, crumbling, or nonexistent sidewalks occlude pedestrian movement. Del Mastro laments that in America, walkability has become obsolete. And he explains his concerns about cars with an intriguing observation about the life cycle of technological progress:

As a product category becomes obsolescent, it is usually the highest-end models that disappear from the market first. That is probably because the consumers who can afford that high-end version are the same ones who become early adopters of the newest innovation. The bottom rung of the old category, however, persists.

Del Mastro describes a wider trend whereby luxuries become necessities. Technology only recently dreamt up can quickly become indispensable by elbowing out slightly older ways of doing things. His first example is air conditioning, an invention so beloved that muggy Florida erected a statue in honor of its creator in the U.S. Capitol:

Sometime in the mid-to-late twentieth century, the box fan began to disappear as the standard means of cooling a home. Before widespread central air conditioning, box fans were sturdy, heavy mechanical marvels. Many were all-steel construction, including the blades, which usually numbered five. These blades were steeply angled to produce greater airflow, which in turn required a heavy, powerful motor. The most advanced models were electrically reversible, meaning that they could go from pushing old air out to pulling fresh air in, with the flip of a switch. Even the cheapest models — the big-box or department-store brands rather than the Lakewoods or General Electrics — were more powerful than any diminutive, flimsy box fan on the market today.

What happened? Cheap air conditioning made it increasingly unnecessary to ventilate or cool with fans. Expensive, top-of-the-line box fans became redundant or obsolete. Over time, they shrunk, and today all of them are smaller and lighter than even a K-Mart model from the 1970s.

But not every building or home has central air, or windows that can easily accept a window AC unit. Most middle-class Americans today probably think box fans are for generating airflow in damp basements or cooling off freshman dorm rooms. But for the families living in old buildings or houses without AC, it is no longer possible to buy a really good fan. The advancement and affordability of a superior technology has made a small but non-zero number of people worse off.

And as consumers upgrade their devices more frequently, this trend becomes most noticeable with the technologies we use to entertain ourselves:

The same thing happened with cassette tape players, CD players, and VCRs. The last cassette tape transport mechanism made anywhere in the world is a Chinese clone of a budget Japanese design, used for low-end boom boxes or portable players. The last VCRs on the market were flimsy, plasticky models — some of which literally had corners cut, sporting fat T-shaped cases to save material in the interior areas that didn’t house any guts of the machine.

New inventions both add onto what came before and subtract from the available options. Innovation is like an emulsifier — a substance that makes it possible to mix together that which should not blend, such as oil and water. And so, progress and regress unexpectedly commingle.

Economist Joseph Schumpeter popularized the evocative phrase “creative destruction” to describe the nature of innovation. But this process is not unique to technology or modernity. In the Origin of Species, Charles Darwin explained how “extinction of old forms is the almost inevitable consequence of the production of new forms.”1 Box fans and cassette decks are endangered species. Del Mastro worries that so, too, are walkable cities:

Something similar has happened with the car and what it has replaced — at a far larger and more consequential scale — but it is harder to discern because there is not some single obsolescent technology that has stuck around in a degraded state to serve the bottom of the market. Rather, the car has deteriorated conditions for those without it and outside it, whether through risks to pedestrians, or through pollution, urban highways, or infrastructure and design based on the assumption that “visitor” and “customer” necessarily mean “motorist.” It is frequently dirty, dangerous, and simply unpleasant to meaningfully get around without a car in most of America today.

The broken or missing sidewalks, the uncrossable expressways, the gutted cities, the strip malls that border housing developments but cannot be walked to, the unsheltered stops where a bus may stop once an hour, the thousands of grisly, violent cyclist and pedestrian deaths that are written off as a cost of doing business — these are the junky VCRs and boom boxes, the lousy box fans. The car has deteriorated carless life in a diffuse and multifaceted way, in the same manner that the smartphone has deteriorated non-digital life. QR code menus, online reservations, the general expectation of connectivity: these developments leave those without them worse off than they were before.

In the case of cars and their associated land use, however, the high end of the old market has not completely disappeared. Depending on their condition, old-fashioned, pre-car urban neighborhoods are widely viewed as being either for the very poor or the very rich. Perhaps it’s not contradictory. In one case, it’s the kid who couldn’t afford a CD player and gets by with his scratched-up records and ceramic-cartridge record player welded atop a busted double-cassette deck. In the other case, it’s the audiophile who thinks he can distinguish between the audio output of a $10,000 turntable and a $20,000 one.

This partly explains why the only truly walkable American metropolis competes to be the most expensive city in the world. A high cost of living buys the option to reject car ownership without sacrificing mobility. For me, at least, this was the reason why I moved to New York City.

But many Americans prefer the suburbs, considering the city dirty, loud, and crowded. Yet these drawbacks are largely (though of course not entirely) caused by cars. Try to imagine New York City without millions of vehicles2 venting exhaust, rumbling when they're moving or honking when they're not, and consuming a whopping 44% of street space just for parking when they aren't even in use. Though highly walkable, unfortunately even New York suffers from plentiful negative externalities imposed by driving — thus the push for congestion pricing. Conversely, European cities that curtail cars in their traditional centers rarely elicit the same apprehension from American suburbanites when they walk from one tourist destination to another in historic gems like Florence and Copenhagen.

Del Mastro's description of American streets being “frequently dirty, dangerous, and simply unpleasant to meaningfully get around without a car” points to a negative feedback loop. When walking is miserable, people value car ownership more, which in turn requires more infrastructure to support increasing numbers of cars, leaving less room for walkability, so that walking becomes more miserable still. He contends that there is “a certain misanthropy that is almost inherent in the act of driving":

The car has effectively rendered the traditional city obsolete. Or to put it slightly differently, the car is not backward-compatible with the city. You cannot stick cars in old cities any more than you can stick a CD in your cassette player. And so the old cities went (at least in America and most places). Urban renewal was a revolutionary phenomenon aimed at retrofitting a traditionally urban landscape for easy motoring. It was evil, but there was little mens rea in it. The planners and businessmen who demolished our historic cities no more understood themselves to be committing a great crime than did the consumers who chucked their faded old tube sets for sleek LCD televisions.

But then, perhaps, neither did the Jacobins or the Bolsheviks.

In their fervor to enable the automobile, these revolutionaries were shamefully incurious about the usefulness of traditional, walkable cities. They did not stop to think before tearing them down. It is a perfect example of Chesterton's Fence, a metaphor devised by philosopher G. K. Chesterton to describe the foolhardy mindset of some who would restructure society:

In the matter of reforming things, as distinct from deforming them, there is one plain and simple principle; a principle which will probably be called a paradox. There exists in such a case a certain institution or law; let us say for the sake of simplicity, a fence or gate erected across a road. The more modern type of reformer goes gaily up to it and says, “I don’t see the use of this; let us clear it away.” To which the more intelligent type of reformer will do well to answer: “If you don’t see the use of it, I certainly won’t let you clear it away. Go away and think. Then, when you can come back and tell me that you do see the use of it, I may allow you to destroy it.”

Similarly, the planners and businessmen who demolished America’s historic cities were blind to the logic of how communities were structured. It seems no one told them to first wonder why walkability matters, so that they would consider the consequences of slicing up cities with highways, and then perhaps reconsider. Faced with the obstacle that cars are not backward-compatible with historic cities, they destroyed what they failed to understand.

Chesterton explained that:

This paradox rests on the most elementary common sense. The gate or fence did not grow there. It was not set up by somnambulists who built it in their sleep. It is highly improbable that it was put there by escaped lunatics who were for some reason loose in the street. Some person had some reason for thinking it would be a good thing for somebody. And until we know what the reason was, we really cannot judge whether the reason was reasonable. It is extremely probable that we have overlooked some whole aspect of the question, if something set up by human beings like ourselves seems to be entirely meaningless and mysterious.

There are reformers who get over this difficulty by assuming that all their fathers were fools; but if that be so, we can only say that folly appears to be a hereditary disease. But the truth is that nobody has any business to destroy a social institution until he has really seen it as an historical institution. If he knows how it arose, and what purposes it was supposed to serve, he may really be able to say that they were bad purposes, or that they have since become bad purposes, or that they are purposes which are no longer served. But if he simply stares at the thing as a senseless monstrosity that has somehow sprung up in his path, it is he and not the traditionalist who is suffering from an illusion. We might even say that he is seeing things in a nightmare.

Ironically, Governor Hochul seemingly drew on the wisdom of Chesterton's Fence when she explained her about-face on congestion pricing. By citing economic concerns and worrying that implementation “risks too many unintended consequences,” she fretted over tearing down the fence of car supremacy. But her excuses ignore the example of Singapore, a city-state that pioneered the concept successfully and has a thriving economy. Worse, she disregards how congestion pricing was an attempt at mitigating unintended consequences from the automobile revolution to restore traditional walkability for New Yorkers. Prioritizing cars over walkability has indeed become what Chesterton called a “bad purpose.”

Because of the brash dismantling of our historic cities, there is nowhere in America where someone can escape cars. Even in New York, the pedestrian experience is famously summed up by Dustin Hoffman's Ratso slamming his hand down on the hood of a cab, bellowing, “I'm walking here!” And because individual choices are largely impotent, communities must decide whether motorist or man is the fundamental unit of society:

The widespread adoption of the car becomes, at some point, a process one cannot simply opt out of, because it is not possible to introduce mass car ownership and hold everything else constant. Below the level of the society or community, the ability to choose breaks down. This is true for those who do not choose to drive, as much as for those who do.

As a community, New Yorkers tried to reassert the value of walking. Was it so audacious to insist that pedestrians be burdened less by steaming fumes, hostile horns, and the threat of blunt trauma? Perhaps congestion pricing failed, in part, because we forgot what it was like to walk unencumbered:

Like all successful revolutions, the automobile revolution obliterated the memory of what came before and established itself as a staid, respectable status quo.

And Del Mastro describes our circumstances forthrightly:

There is a sort of philosophical end-user license agreement to which we assent when we climb behind the wheel… that freedom of movement demands a sacrifice in blood.

Once your own blood has been spent on that altar, the veil falls from that “staid, respectable status quo" to reveal an existential threat. About ten years ago, an SUV nearly severed my left foot, mangling my leg so badly that one of my surgeons told me I might be better off with an amputation. And so, I must admit unbridled rancor towards the automobile revolution.

When I cross the streets of New York with my children, I often remember 7-year-old Kamari Hughes, who was cut down by a truck in Brooklyn last year. He was walking to school beside his mother, who was pushing his sibling in a stroller, when the driver rushed through a yellow light to make a right turn. A witness “said that after the collision, the child’s mother chased the tow truck down the street, screaming that the driver had killed her baby. ‘The mother just started screaming at the highest pitch… That was heart-wrenching.’” As my young children grow up, someday I will have to let them cross the street without holding my hand. The thought tightens my throat.

Losing walkability was a brutal tragedy. Americans have optimized safety for children in so many other ways — perhaps too much, so that some parents fret even about the risks of sleepovers, resulting in a profoundly anxious generation — while simultaneously tolerating the omnipresent possibility that a hurtling hunk of metal may steamroll their tiny bodies. Balking at this horror, some countries did backtrack, like the Netherlands in the 1970s when thousands protested Stop de Kindermoord (“stop the child murder”) until pedestrians and cyclists regained the right of way.

Del Mastro describes this as, “A society that could still be moved by the violent death of children.” Maybe that is too harsh. At least the New York Times covered the killing of Kamari Hughes, while newspapers consider the vast majority of car accidents hardly worth mentioning.

Despite all this barbarity, my hatred for cars is not characterized by despair. Just as the course of history eventually cast down the Jacobins and Bolsheviks, the automobile revolution will crumble. Del Mastro is correct to bemoan that “it's too late to turn back" from America's car saturated cities, but turning back is unnecessary. Cars will lose for the same reason that they once won — by becoming the next victims of creative destruction.

It is reasonable to hope that whatever technology ascends in place of cars will be safer and cleaner. Just consider the headline-grabbing outrage when a driverless vehicle kills someone, whereas it takes the drama of a mother running screaming after her child's murderer for the papers to cover a regular car accident. When the time comes to dethrone cars, we may demand a higher standard.

Progress ushered in this era of asphalt and carnage; progress will vanquish it in due course.

Darwin, Charles. “Chapter Eleven: On the Geological Succession of Organic Beings.” On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, 6th ed., The Easton Press, Norwalk, Conneticut, 1872, p. 324.

According to the NYC Department of Motor Vehicles, there are 2.2 million cars registered in NYC. Nearly another million private vehicles drive into just the southern half of Manhattan daily, which is the business district and the area that would have imposed congestion pricing. And then there are 13,587 taxis and over 120,000 commercial vehicles that enter Manhattan every day.