On Jonah Goldberg’s “Threat Level Midnight Forever”

An Idea Worth Drawing For.

This visual essay is a tribute to Jonah Goldberg. It’s part of an ongoing series called Ideas Worth Drawing For, in which I make hand-drawn images to honor the excellence of essayists I admire.

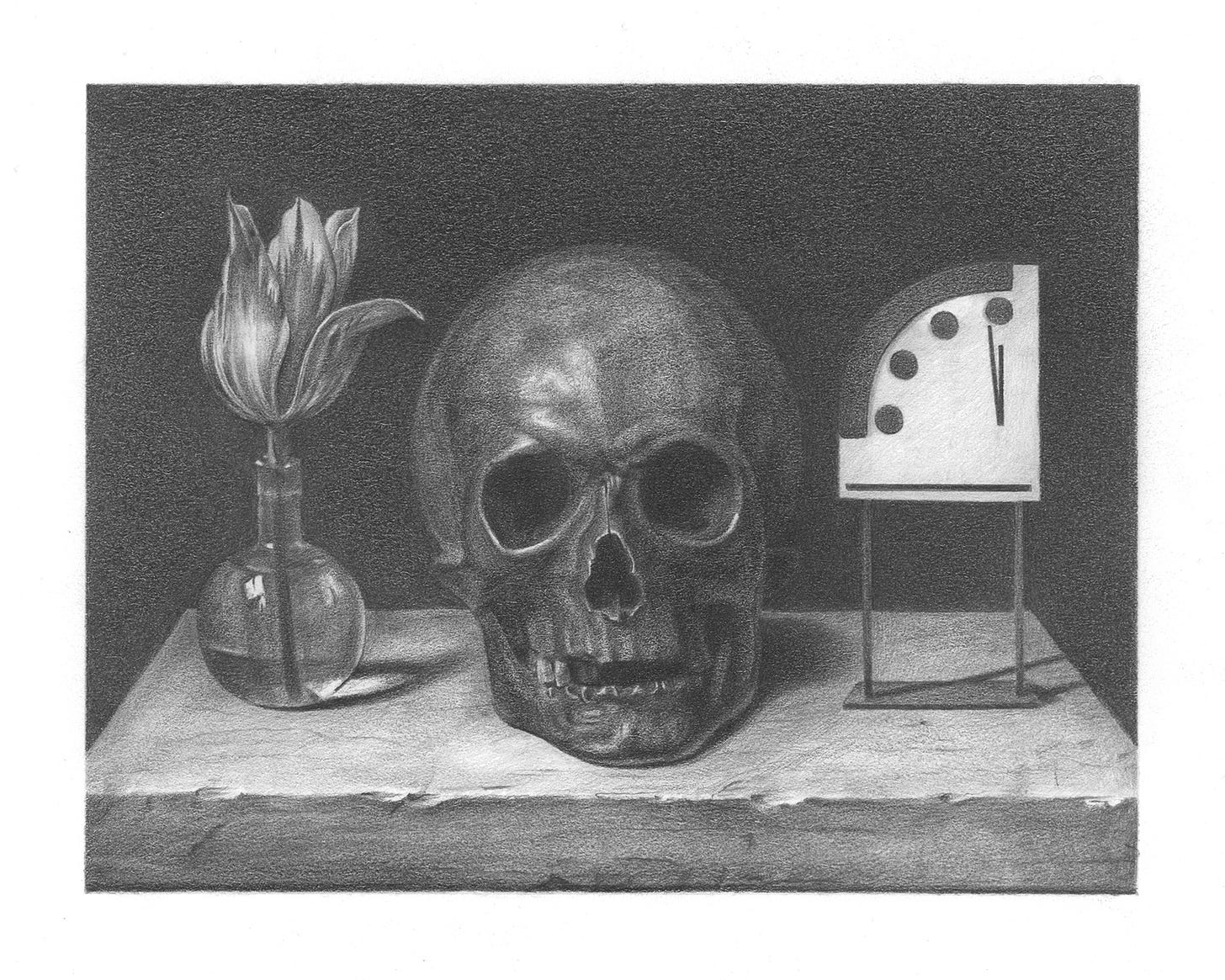

Humanity has coped with mortality by making memento mori like Philippe de Champaigne’s 17th century painting “Still Life with a Skull,” which features a tulip, a skull, and an hourglass — life, death, and time — lined up in a row. In the 20th century, as mushroom clouds dissipated over Japan, dread of individual death metastasized into angst about collective annihilation. Nuclear weapons produced both literal and psychological fallout, and a popular symbol of the latter is the Doomsday Clock set by the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, an organization formed in 1945 by some former Manhattan Project physicists anxious to defang the weapon they helped invent.

The Doomsday Clock, originally set at 7 minutes to midnight, was designed to suggest how close humanity is to destroying itself. Its clock hands hover before the metaphorical midnight of apocalypse. At the beginning of this year, the Bulletin announced that, “The Clock now stands at 90 seconds to midnight — the closest to global catastrophe it has ever been.”

In response, the writer Jonah Goldberg nominated the Doomsday Clock as the most successful publicity stunt in history. In his essay “Threat Level Midnight Forever” at The Dispatch, Goldberg explains why:

It is very difficult for any advocacy group to get this kind of coverage at all. But it is infinitely more difficult to get media outlets to credit the opinion of such groups as objectively authoritative. Getting this kind of fawning, deferential coverage for 76 years makes the marketing mavens and Michael Scarns at the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists arguably the GOAT of spin.

So here’s the first problem. There’s nothing particularly “scientific” about the clock. There’s no complicated risk-assessment algorithm or anything resembling the scientific method involved. It’s just a bunch of experts expressing an opinion and boiling it down to a dopey clock intended to scare the bejeebus out of people.

Goldberg argues that the patina of science lends credibility where it is not due:

But physicists, biologists, volcanologists, and computer scientists aren’t much use in telling me whether—or when!—Vladimir Putin will use a nuclear weapon, and they’re even less useful in telling me how the world will respond. I might buy what they’re selling on more sciency topics like climate change, but that doesn’t mean I have to accept their remedies, because climatologists have no special expertise in statecraft or economics. The scientists can tell me that Godzilla is coming, but I’m gonna want some input from the generals about how to stop him.

Indeed, as is often the case with very smart people, their advice may be counterproductive because really smart experts often don’t understand that they’re not experts about stuff they’re not experts on.

But again, the Doomsday Clock isn’t really about science. And to their credit, the people behind it often admit as much. They concede it’s just a metaphor.

…

But the Bulletin, despite its concessions to metaphorical guesswork, is happy to fall back on appeals to its own authority, like Bill Murray in Ghostbusters. “Back off man, I’m a scientist.”

Could the situation be improved if the Doomsday Clock was recalibrated with a complicated risk-assessment algorithm? Alas, this would not elevate the symbol from metaphor to metric. The entire premise of measuring our proximity to self-destruction is flawed.

Calculating the odds and consequences of random mistakes is impracticable. Did you know that the U.S. Air Force accidentally dropped a couple nukes on North Carolina when an aircraft broke apart mid-flight in 1961? People quibble over how close one of those 3.8 megaton H-bombs came to detonating. This is but one historical “close call” with nuclear weapon mishaps, and foreign policy wonks acknowledge that analyzing such case studies cannot lead to confident risk assessments. Happenstance alone compromises any attempt at quantifying the likelihood of global catastrophe.

The Bulletin urges humanity to “turn back the clock” by checking risky behavior, but the proper cliché is “you can’t put the genie back in the bottle.” Nuclear weapons cannot be un-invented. Virologists cannot unlearn how to synthesize pox viruses from scratch. However much we argue about the ramifications of artificial intelligence, progress on AI marches on. Luddites have never won the argument.

“Defenders of the Doomsday Clock say I’m missing the point,” Goldberg continues, “They’re simply warning us about the dangers we face. Some might even say that such warnings helped to prevent calamity. Eh, maybe. But does anybody at this point really need to be told that nuclear war would be bad?”

And if the Bulletin thinks that admonishing people to be careful works, then they should read investigative reporter Alison Young’s new book Pandora’s Gamble: Lab Leaks, Pandemics, and a World at Risk. She demonstrates, through plentiful examples, how even the hazard of contracting diseases with astronomical mortality rates is not incentive enough for lab workers to stop flaunting established safety protocols. Frequently, researchers don’t want to wear cumbersome protective gear or quarantine after known exposures to dangerous pathogens — too inconvenient!

At this point, no one needs to be told that nuclear war would be bad, but more people might like to know about the perils of carelessness. “What I had come to learn,” Young writes, “through more than a decade of reporting on these failures, was that the only thing rare about lab accidents was the public finding out about them.”

There is a longstanding culture in microbiology to take risks and keep them secret. If we don’t accidentally nuke ourselves, then we might just let slip a plague far deadlier than the COVID-19 pandemic because some virologist didn’t feel like isolating after a bite from an infected lab rat.1 And a complete cultural overhaul of the field of microbiology is beyond the purview of the Doomsday Clock.

Given that curbing hubris is not humanity’s strong point, what has the Bulletin accomplished with their Doomsday Clock? Goldberg criticizes them for using the Clock “as a cudgel against anyone not wholly bought into various arms control doctrines and various peacenik pieties.” He describes one unintended consequence of the Bulletin harping on about risk:

While I’m tempted to rehash Cold War arguments about deterrence and the like, let me make the same point in the current context. Last week, for the first time, the Doomsday Clockers issued their report in Russian and Ukrainian. They moved the clock forward because of the Russian invasion, and while the clocksters are not supportive of Putin’s crimes, they are nonetheless providing useful propaganda for him. It is Russia, and Russia alone, that insists this war could force the Russians to use nuclear weapons. It’s a threat they invoke constantly to shake Western resolve. If people believe Russia and Vladimir Putin lack agency to stop the war, they calculate, NATO and Ukraine will cave to the inevitability of Russian victory.

It’s no surprise, then, that the Kremlin responded to the report with great seriousness, because Russia wants everyone to be terrified of nuclear war, and the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists gave them a huge P.R. coup by lending “scientific” credibility to their threats. Of course, Russia blamed America and NATO for the increased risk, because it is a staple of Russian propaganda that they’ve done nothing wrong and that it’s NATO and Ukraine that are being “provocative” for not taking the position that the rape victim should just lay back and take it.

…

This has been the role of the Bulletin for 70 years, to pressure Western leaders to pursue the Bulletin’s arms control priorities. Whatever you make of that project, it’s just an ideological argument masquerading as science.

If you gauge the value of the Doomsday Clock by the words and actions of the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, then you may miss its true purpose. It seems that even the Bulletin does not realize what their Clock is actually for, if they believe it to be a political tool for averting annihilation.2 Their efforts are futile.

As the memento mori of the modern age, the Doomsday Clock is diametrically opposed to its creators’ wishes. Memento mori are stoic devices for embracing death, not escaping it.

The poet Mary Oliver knew this when she wrote:

when death comes

like an iceberg between the shoulder blades,I want to step through the door full of curiosity, wondering:

what is it going to be like, that cottage of darkness?…

When it’s over, I don’t want to wonder

if I have made of my life something particular, and real.

I don’t want to find myself sighing and frightened,

or full of argument.I don’t want to end up simply having visited this world.

Memento mori advise, “Remember you must die.” When 17th century artists painted hourglasses into their vanitas still lifes, they never considered how they could “turn back the clock.” The point is to accept the transience of life with dignified resolve to not squander your fleeting existence.

The Doomsday Clock applies this logic to the entire species; therefore, as a memento mori, it demands more of us. Collective annihilation inspires greater dread than an individual life extinguished, because it removes the comfort of leaving behind children and a legacy when we cross the River Styx. Extinction has more finality.

Humanity probably has an expiration date. In our stupidity, we may let ourselves spoil prematurely like leftovers that no one bothered to put in the fridge.

Can we accept this fate with dignified resolve?

If you follow that link, you’ll find a list of safety breaches that include two mice bite incidents. Note that in 2016, when a mouse infected with a SARS-like virus bit a researcher so hard that the wound bled, the researcher was not expected to quarantine. But in April 2020, after the COVID-19 plague had taken off, a researcher with a mouse bite that didn’t break the skin was asked to quarantine for 14 days. In Pandora’s Gamble, Young points out how our most recent plague seemed to have chasten the researchers in this particular coronavirus lab. I highly recommend Young’s book, because her reporting is far more detailed and accurate than descriptions of such anecdotes that you can find online.

The Bulletin seems to suffer from a classic art student frustration: In art school, we have “critiques” where the professor and classmates gather ‘round to discuss each student’s artwork. Quite often, no one discerns what the artwork “is about” according to its creator. If the professor tells each student to stay quiet while their classmates critique the artwork, and only lets the student explain what their art is supposed to mean after everyone else has had a go at it, the student will frequently reveal a meaning that no on in the class had guessed. This is the novice version of an artwork “taking on a life of its own.”