On Stephen Fry's “In Touch With The Inner Adult”

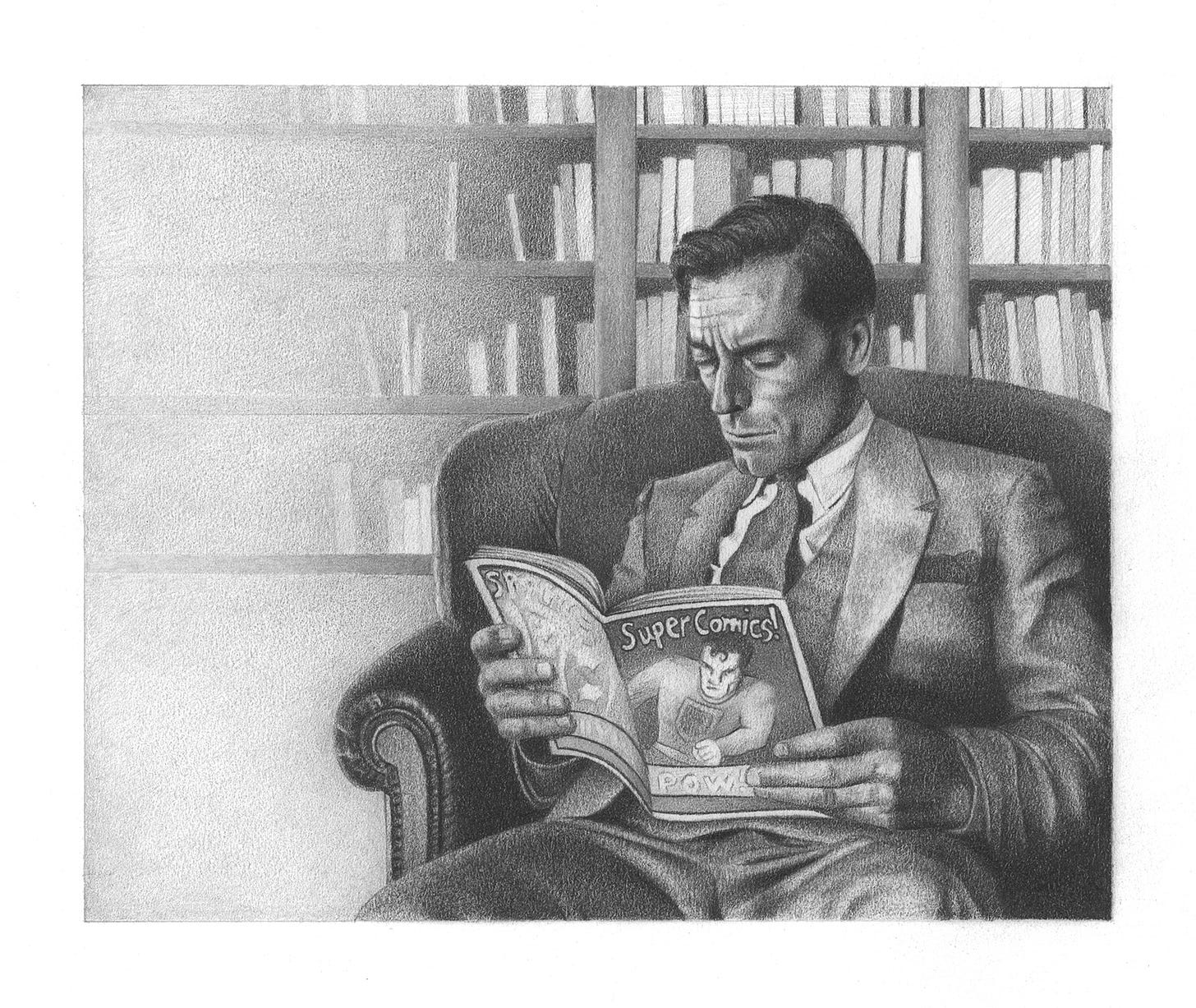

An idea worth drawing for.

This visual essay is a tribute to Stephen Fry. It’s part of an ongoing series called Ideas Worth Drawing For, in which I make hand-drawn images to honor the excellence of essayists I admire.

Comic books are a key influence on my visual essays. They are a perfect marriage of drawing and writing. You could never enjoy comics as audiobooks, and I hope you feel that way when you read Fashionably Late Takes.

Some people are touchy about terminology and prefer the term graphic novel. On one level, this is like the distinction between a novel and a short story or chapter — longer story arcs are bound in thick volumes that we call graphic novels, while shorter issues are comic books. But the term graphic novel is also used to distinguish between highbrow and lowbrow.

No one calls Art Spiegelman's Maus a comic book. This is not just because they’re referring to the full compilation of chapters that were initially serialized in the Raw comics anthology that Spiegelman edited in the ‘80s. It is because Maus was groundbreaking for proving that comics can be serious and grownup. Spiegelman wrote a memoir about how his relationship with his father was shaped by the elder Spiegelman's imprisonment in a Nazi concentration camp. Maus is firmly part of the pantheon of great literature about the Holocaust.

Another great comic book author, Neil Gaiman, explained the pretentious attitude towards comics with this anecdote:1

Once, while at a party in London, the editor of the literary reviews page of a major newspaper struck up a conversation with me, and we chatted pleasantly until he asked what I did for a living. "I write comics," I said; and I watched the editor's interest instantly drain away, as if he suddenly realized he was speaking to someone beneath his nose.

Just to be polite, he followed up by inquiring, "Oh, yes? Which comics have you written?" So I mentioned a few titles, which he nodded at perfunctorily; and I concluded, "I also did this thing called Sandman." At that point he became excited and said, "Hang on, I know who you are. You're Neil Gaiman!" I admitted that I was. "My God, man, you don't write comics," he said. "You write graphic novels!"

He meant it as a compliment, I suppose. But all of a sudden I felt like someone who'd been informed that she wasn't actually a hooker; that in fact she was a lady of the evening.

For my part, I have stubbornly avoided the term graphic novel in defiance of the insinuation (or explicit scorn) that comic books are too lowbrow. As an art medium, comics explore how literature and drawing can enhance each other. So what if children discovered this joy first?

Though I tend to bristle when someone seems to denigrate this art form as childish, the writer and comedian Stephen Fry broached the subject with finesse in his essay “In Touch With The Inner Adult.” Perhaps Fry bypassed my irascibility by opening his essay gingerly:

Great care needed here. One of those instances where a fellow has to make it perfectly clear that Observation Is Not Necessarily Criticism.

A person – writer, comedian, broadcaster say, sees — or thinks they see — a trend, a mode, a manner, a style, and they remark upon it. But the remarking can be read as mockery or disapproval, and those observed take umbrage.

…

People are prickly these days… Along with snowflakery and triggering comes a strong hypersensitivity to criticism or, most painfully, scorn. Even if criticism or scorn were never there, just a friendly note.

After appeasing us sensitive souls with this throat clearing, Fry teases out how childish things seeped into adulthood:

Just noticing that we seem to be clinging on to childhood and its appurtenances and resisting the blandishments of adulthood for the first time, surely, in our history.

The most striking part of Fry’s observation is how this development is unprecedented. A transformation that upends the status quo is intriguing, and it demands introspection. Fry mentions comic books a few times throughout his essay as an example of how times have changed (original emphasis):

Grownups though. Grownups had different music, different food, different clothes, different books, different films, a different language, different everything…

The time would come when we would pass through the veil that separated childhood from adulthood… And we more or less did. We morphed from schoolkids into students. From students into young people. We got jobs. We booked holidays and organised mortgages for ourselves. We put away childish things. We…

But wait — somewhere, somehow, we started to look not forward to more maturity but back to … to what? It was partly a bonding kind of nostalgia… People began to confess that they had kept their Marvel or DC comics from long ago. And were reading them again.

And though Fry takes care not to scorn the trend, his observation made me wonder, for the first time, if there might be a trade-off to devoting a very large bookshelf to my comic book collection. After all, my apartment is tiny. Despite my best efforts to cloak the walls with bookshelves, I cannot own every good book. Should I fill those shelves instead with more volumes of history, or dense philosophical treatises? What does it say about me that Batman enjoys an entire shelf, but I do not own Homer’s Illiad or Odyssey?2

Then again, Homer’s epic poems emerged out of an oral tradition. The ancient Greeks listened to their poets. Unlike comic books, you could enjoy the Odyssey immensely as an audiobook.

With a tap, I just bought the audiobook, so I’m no longer ashamed of the Homer-sized hole in my bookshelf — and it’s narrated by Ian McKellen! You may know him as Gandalf from Lord of the Rings or Magneto from X-Men.

But before I can begin the Odyssey, I must finish every Dune novel. (I’m on my seventeenth audiobook in that expansive sci-fi series, which has taken about 330 hours, or almost 14 days, and counting.) Listening to Homer’s epic poem is surely the more grownup choice. But can I put away childish things? I have not solved my problem by expanding my bookshelves with soundwaves.

And that problem is what the poet Andrew Marvell expressed:

Had we but world enough and time

I learned that snippet of poetry from Douglas Murray's “Things Worth Remembering" series.3 His year-long column featured poetry that he had memorized. Few among us know about fifty poems by heart. Could I match his intimidating intellect if instead of using up a fortnight of my life on Dune, I made an effort to store T. S. Eliot or W. H. Auden in my memory? Am I using my finite existence wisely?

Fry muses about whether we can have it all by oscillating “between our profound grownup savoury, serious selves and our shallow sugary, fun-loving silly selves.”

George Orwell wrote in Nineteen Eighty-Four, ‘If you want a picture of the future, imagine a boot stamping on a human face – forever.’

Maybe a more accurate (and equally terrifying) prophecy would be, ‘If you want a picture of the future, imagine Veruca Salt stamping her foot and crying “I want it now!”’– for ever.’

But we have neither world enough nor time to have it all. Within our short lives, we must figure out what is edifying and what is indulgent. I could write a treatise about how Batman stories explore the theme of redemption every bit as well as Les Misérables, but I may just be making elaborate excuses for clinging to childish things.

And maybe the push to distinguish highbrow from lowbrow with the term graphic novel is an appropriate insistence on the necessity of growing up. To aspire to be nothing like Veruca Salt.

Of course we should revel in the magic of merging words with drawings, but with sophistication. Or at least sometimes. We should put away childish things in moderation — which is a very grownup answer to the problem.

But there is greater answer: have children. Put the large bookshelf full of comics in their bedroom. Parenthood means you do not put away childish things; instead, you pass them on.

Bender, Hy. The Sandman Companion (New York: Vertigo, DC Comics, 1999), 4.

In my defense, I did read the Odyssey for a college course, though that was over fifteen years ago now, and I don’t know what happened to my copy of the book.

On Douglas Murray's "Things Worth Remembering"

Two years before his death, the poet W. H. Auden explained that the arts are “our chief means of breaking bread with the dead. After all, Homer is dead, his society is gone, but we can read The Iliad and find in it significance and meaning. And I personally think without communication with the dead a fully human life is not possible.”

Wonderful! Your essay immediately brought to mind the section entitled "Children" in Tolkien's classic essay "On Fairy-Stories."

Only thing I disagree with here is categorizing Dune as being at all 'childish things'. Epic Cycle it is not, but one for the ages it very much is.

REALLY dig what you do here. It's giving me ideas...