The Religious Instinct in a Godless World

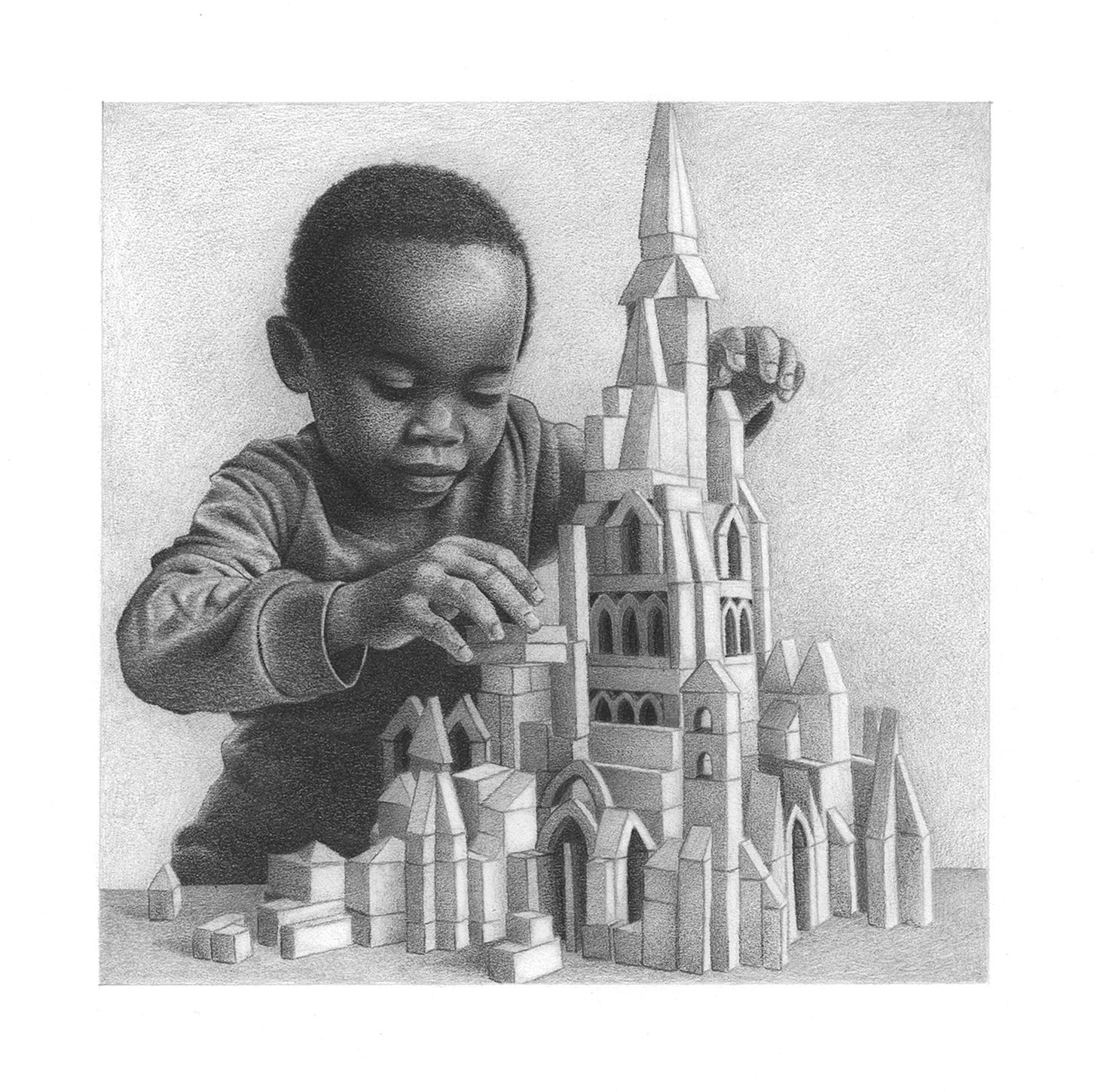

The religious urge is born into nearly every child. And when we do not inherit a belief system, we build our own temples.

This visual essay first appeared in Quillette on May 9, 2024.

It’s an offshoot of my ongoing series called Ideas Worth Drawing For, in which I make hand-drawn images to honor the excellence of essayists I admire. I regularly contribute visual essays to Quillette that spotlight pieces from the magazine’s archive.

There is nothing wrong with constructing our own human meaning, without invoking a god. But the risks involved are captured by a pithy insight attributed to G.K. Chesterton: “When men stop believing in God they don't believe in nothing; they believe in anything.” As people have argued since at least 1790, when Edmund Burke published his Reflections on the Revolution in France, sapping society of traditional religious belief can prepare the way for new ideologies controlled by murderous totalitarians like Robespierre—and later, Stalin and Mao.

In “Our Search for Meaning and the Dangers of Possession,” Jungian analyst Lisa Marchiano details how a misplaced religious urge can derail both individuals and societies. She opens with variations on Chesterton’s theme:

“There is no such thing as not worshipping,” wrote novelist David Foster Wallace. “Everybody worships. The only choice we get is what to worship.” C.G. Jung would have wholeheartedly agreed. He posited that psychic life is motivated by a religious instinct as fundamental as any other, and that this instinct causes us to seek meaning. “The decisive question for man is: Is he related to something infinite or not?” Jung wrote in his autobiography. “That is the telling question of his life.”

There is empirical evidence that backs up Jung’s idea of a religious instinct. Researchers have found that the less religious people are, the more likely they are to believe in UFOs. “The Western world is, in theory, becoming increasingly secular—but the religious mind remains active,” writes psychology professor Clay Routledge, in The New York Times. He notes that belief in aliens and UFOs appears to be associated with a need to find meaning.

As the famous UFO poster from The X-Files put it, “I want to believe.”

Maria Popova has described the atheist’s need for meaning as equal parts poetic and tragic:

How do we manufacture this feeling of meaning given we are the product of completely austere impersonal forces and we are transient and we will die and return our borrowed stardust to this cold universe that made it?

Popova is riffing off astronomer Carl Sagan’s famous pronouncement that, “The cosmos is within us. We are made of star-stuff. We are a way for the cosmos to know itself.” The original Sagan sentiment is all starry-eyed wonder; Popova’s variation emits the agony of a sentient being balking at mortality. For some of us, having an expiration date imbues the search for meaning with both urgency and desperation. How we choose to cope defines our lives.

Marchiano cautions that worshipping the wrong thing can have dire consequences. She quotes David Foster Wallace:

The compelling reason for maybe choosing some sort of god or spiritual-type thing to worship—be it JC or Allah, be it YHWH or the Wiccan Mother Goddess, or the Four Noble Truths, or some inviolable set of ethical principles—is that pretty much anything else you worship will eat you alive.

Traditional religions do have features that make them less likely to become devouring. They draw on ancient traditions that are often philosophically rich, and they are knitted into the social structure of our society.

Famous atheist Ayaan Hirsi Ali heeded this warning when she declared in November 2023 that she is now a Christian—an apostate from apostasy. The first reason she gave for converting to Christianity is her new-found conviction that liberal democratic civilisation depends on the legacy of the Judeo-Christian tradition:

That legacy consists of an elaborate set of ideas and institutions designed to safeguard human life, freedom, and dignity—from the nation-state and the rule of law to the institutions of science, health, and learning. As Tom Holland has shown in his marvelous book Dominion, all sorts of apparently secular freedoms—of the market, of conscience, and of the press—find their roots in Christianity.

And so I have come to realize that [Bertrand] Russell and my atheist friends failed to see the wood for the trees. The wood is the civilization built on the Judeo-Christian tradition; it is the story of the West, warts and all. Russell’s critique of those contradictions in Christian doctrine is serious, but it is also too narrow in scope.

And the second reason Hirsi Ali gave is that she ultimately found life without any spiritual solace unendurable:

Atheism failed to answer a simple question: What is the meaning and purpose of life?

Russell and other activist atheists believed that with the rejection of God, we would enter an age of reason and intelligent humanism. But the “God hole”—the void left by the retreat of the church—has merely been filled by a jumble of irrational, quasi-religious dogma.

Hirsi Ali concludes that “the erosion of our civilization will continue” without “the power of a unifying story.” And in this regard, she pronounces that, “Christianity has it all.” Notably absent from her road to Damascus moment is any profession of belief in the divinity of Jesus Christ1—her religious urge is bound up with her distress at the dire consequences of worshipping the wrong thing.

Her friend Richard Dawkins has responded that atheists have many avenues for finding meaning and purpose. First among them, for the evolutionary biologist, is science:

Then there’s human love, there’s the beauty of a child, a tropical swim under the stars, a ravishing sunset, a Schubert quartet. There’s the art and literature of all the world. The warmth of an intimate embrace.

But even if all such things leave you cold—and of course they don’t—even if you feel a ravenous need for more, what on Earth does that have to do with the truth claims of Christianity or any other religion? Even if life were intolerably bleak and empty—it isn’t, but even if it were—how could you, how could anyone, twist a need for solace into a belief in scriptural truth claims about the universe, simply because they make you feel good? Intelligent people don’t believe something because it comforts them. They believe it because, and only because, they have seen evidence that supports it.

No, Ayaan, you are not a Christian, you are just a decent human being who mistakenly thinks you need a religion in order to remain so.

Marchiano challenges the strength of what Dawkins calls the “poetry of reality” with a series of case studies of individuals under the grip of “psychological possession,” a state in which “the conscious personality comes to identify with a powerful archetypal idea or image, becoming inflated and dangerously out [of] balance.” Those individuals either disregarded the poetry of reality or found it insufficient to satisfy their religious urges.

Marchiano’s first case study concerns Timothy Treadwell, whose life and death among Alaskan grizzly bears is documented in Werner Herzog’s 2005 film Grizzly Man. Treadwell was eaten alive by the bears in 2003. Marchiano writes:

Enthusiasm comes from the Greek meaning “possessed by God,” and Treadwell’s rapture as he describes grizzlies has a religious fervor. …

Treadwell developed a distorted sense of mission, believing that his presence in Katmai was necessary to protect the bears from poachers. Protecting bears was his “calling in life,” and he became convinced that he had been singled out to do this work. “I’m the only protection for these animals,” he states emphatically in the film. In fact, there is no evidence that the bears in Katmai were under any threat from poaching. Nevertheless, the sense of mission Treadwell felt in relation to the bears gave him a sense of a special destiny.

Bears carry an undeniably numinous energy and have forever been associated with the divine in various traditions. Treadwell had indeed made contact with the infinite. However, he lacked any structure to ground these experiences.

Like Treadwell, the ground-breaking primatologist Jane Goodall lived among the mighty creatures she studied. Defying the scientific community’s norms, Goodall gave the chimpanzees names instead of numbers, and described them in human-like terms, often attributing their behaviours to emotional states and ascribing to them a theory of mind. This was considered insufficiently objective. Her habit of socialising and making physical contact with the apes is also considered improper today.

But unlike Treadwell, Goodall did not become “possessed.” Far from developing delusions of intimacy with the chimpanzees in Tanzania’s Gombe National Park, her familiarity taught her how readily they could become violent.

Goodall discovered that chimps are not vegetarian, as had been assumed, but hunt other animals for their meat. She observed a war break out between different chimp factions that dragged on for four years. After a particularly violent chimp assaulted her and almost broke her neck in 1989 (towards the end of her thirty years among the animals), Goodall began travelling through their territory with two bodyguards.

Whereas Treadwell’s psychological possession blinded him to the danger posed by grizzly bears, Goodall retained a lifelong fondness for chimpanzees while fully comprehending their capacity for cruelty.

Her greatest discovery was that chimps could fashion tools—an ability previously believed to be a unique, defining feature of humanity. Goodall showed that chimpanzees are more like humans than people had previously realised. Treadwell believed that grizzlies shared in his humanity (or that he shared in their bear-ness), but lacking Goodall’s ability to love animals as they are rather than as he wished them to be, his obsessive and unrequited love led to a foolish death.

So, was there something that inoculated Jane Goodall against psychological possession? If Marchiano is correct that traditional religious belief can be like a vaccine against “becoming inflated and dangerously out [of] balance,” then it is notable that Goodall professes belief in a higher power. In a 2021 interview, she claimed that “religion entered into me” at the age of 16, and:

What I love today is how science and religion are coming together and more minds are seeing purpose behind the universe and intelligence. …

We don’t live in only a materialistic world. Francis Collins drove home that in every single cell in your body there’s a code of several billion instructions. Could that be chance? No. There’s no actual reason why things should be the way they are, and chance mutations couldn’t possibly lead to the complexity of life on earth. This blurring between science and religion is happening more and more. Scientists are more willing to talk about it.

Dawkins would stridently disagree that the complexity of life on earth could not arise from what Popova called “austere impersonal forces.” Indeed, Goodall argues with Charles Darwin himself, who wrote in On the Origin of Species:

If it could be demonstrated that any complex organ existed, which could not possibly have been formed by numerous, successive, slight modifications, my theory would absolutely break down. But I can find no such case.

How curious that the scientist who discovered the kinship between humans and chimpanzees disagrees with the bedrock idea upon which the entire field of evolutionary biology is built: that the complexity of life on Earth results from an eons-long succession of tiny, incremental changes. Goodall uncovered a biological truth while denying a fundamental biological mechanism.

Darwin’s theories have long been at odds with religious belief. Could it be that by rejecting a fundamental aspect of evolution in order to safeguard her traditional religious belief, Goodall protected herself from psychological possession, thereby enabling her contribution to science?

Marchiano might find that argument compelling. She writes:

How do we worship without being eaten alive? A genuinely religious attitude in the psychological sense is an antidote to inflation. The word religion may come from the Latin religare, which means to bind fast, or place an obligation on. In contrast to puffed-up inflation, a religious attitude binds us to something larger, and puts upon us a sacred obligation to the infinite.

An awareness of our dependence upon that which is larger breeds the humility without which wisdom is not possible. It reminds us that our ego is just a small part of us, and is dependent upon—and easily influenced by—irrational, unconscious forces that are beyond our full understanding.

If it is true that few people can safely satisfy their religious urge by simply appreciating the “poetry of reality,” then the pursuit of meaning and the pursuit of truth will sometimes be at odds. Or at least, humanity may come at truth obliquely, or embrace it only partially. Even as we appreciate how religion may safeguard against psychological possession, we should recognise the trade-off: we may have to sacrifice objective truth to the need for psychological or—for people like Hirsi Ali—social stability.

And yet, psychological stability is clearly necessary if we want to pursue truth. It is the difference between a Timothy Treadwell and a Jane Goodall. Some—perhaps many—people may only be able to discover certain truths (the violent behaviour of chimpanzees) by denying others (evolution by natural selection). Atheists will need to swallow that paradoxical and bitter pill. And yet, the religiously minded should not feel too pleased, either. Whatever protection their faith affords them has its limitations.

As Marchiano wisely notes, traditional religions can also become devouring. Conservative intellectual Jonah Goldberg agrees with both her argument and her caveat in his recent essay, “The Messianic Temptation”:

My theory of the case held that believing Christians and other traditional believers are partially immune to such heresies precisely because they don’t have holes in their souls to be filled up by secular idols. The space for God is filled by God. I still believe that.

What I failed to fully account for is that the religious can fall for false idols and false prophets, too. After all, that’s the moral of the golden calf in the first place.

Goldberg describes how he once enjoyed poking fun at some American leftists for discussing Barack Obama in messianic terms—only to discover that many on the American right now talk about Trump delivering salvation. Goldberg recognizes that these are merely new incarnations of an old phenomenon:

At the beginning of the 20th century, champions of eugenics, nationalism, socialism, etc., claimed that Jesus was, variously, the first eugenicist, the first nationalist, the first socialist. Now Jesus is MAGA.

It’s all very depressing. And annoying. But it isn’t really new.

A New York Times correspondent covering the 1912 Progressive Party convention, described it as a “convention of fanatics.” Political speeches were interrupted by the singing of hymns and cries of “Amen!” “It was not a convention at all,” the Times reported. “It was an assemblage of religious enthusiasts. It was such a convention as Peter the Hermit held. It was a Methodist camp meeting done over into political terms.” The delegates sang “We Will Follow Jesus,” but with the name “Roosevelt” replacing Jesus. Roosevelt told the rapturous audience, “Our cause is based on the eternal principles of righteousness. … We stand at Armageddon, and we battle for the Lord.”

Sometimes people think they are serving their god, when they are really making their god serve a politician—a mere mortal in a famously corrupting line of work. Though they didn’t build their own temples from scratch, these people have rearranged the building blocks to incorporate a cause du jour. In such cases, traditional religious belief was an insufficient prophylactic against worshipping the wrong thing.

Nevertheless, Marchiano argues convincingly that traditional religion is one way that people can worship without being eaten alive, because it might inspire humility:

An awareness of our dependence upon that which is larger breeds the humility without which wisdom is not possible. It reminds us that our ego is just a small part of us, and is dependent upon—and easily influenced by—irrational, unconscious forces that are beyond our full understanding.

But Dawkins is right that a sense of wonder is a healthy outlet for atheists with a religious instinct. Scientists like him, as well as laypeople enthralled by what science teaches us, can find humility by studying the natural world. After all, Darwin’s theories were not just an affront to some religious doctrines but also to human pride. People didn’t much care for the idea that humanity was the result of eons of evolutionary nudges rather than divine decree. Believing that we are God’s special creation strokes our ego; believing that we fill an evolutionary niche, neither more nor less successfully than a house fly fills its position in the web of life, does not evoke pride.

Different types of people will be attracted to the theist and atheist options for combatting hubris and the lure of psychological possession. Likewise, there will always be some people who succumb to either the theist or atheist way of being eaten alive. Humility does seem to be the antidote to this, but unfortunately there is no universally guaranteed method for cultivating it.

Since the original publication date, Dawkins and Hirsi Ali had a public and heartfelt conversation about her conversion experience, in which she clarifies that she chooses to believe in the divinity of Christ.

Fascinating topic. Some might argue that science and art express the divine. Or that reality and spirituality are two sides of the same coin producing our much needed humility.

Great post, Megan. It's a nice pairing with your "Curiosity is Sacred" post. I once found myself making the case that humility and curiosity work best when working together. Humility without curiosity could easily lead to a kind of passivity to world. Curiosity without humility can easily lead to a quest for dogmatic certainties.