To Err Is Human

A lesson from the Cold War about risky science.

“Black Saturday” was the most precarious day of the Cold War, and it emerged out of a series of mishaps. Where malice could theoretically be contained by Mutually Assured Destruction, malfunctions went rogue. Airplanes and a submarine nearly fired nuclear missiles. If they had, then Black Saturday would have become the first day of WWIII. This history teaches us how happenstance and errors can compromise safeguards when using scientific discoveries, like nuclear fission, that require utmost care.

If nuclear physics birthed the quintessential example of a scientific-breakthrough-turned-existential-threat in the 20th century, then our 21st century equivalent is born by research on deadly pathogens.1 There is an extensive record of lab leaks where viruses and bacteria weaseled away from the researchers studying them to sicken or kill either the lab workers themselves, their family members, or people living nearby. Much of this is recent history, and many breaches happened in modern high-security biosafety labs that study the most dangerous pathogens.2

Biosafety is contentious because the risks inherent in some research are zero-sum. Either it is too risky to seek out new viruses among animals in the wild because the virus hunters could become patient zero of a novel outbreak, or it is too risky to leave those viruses unknown because we would be unprepared for their inevitable emergence. Either it is too risky to intentionally engineer viruses in the lab to become deadlier or more infectious, or it is too risky to remain ignorant of how those viruses might gain those functions in nature.

Since the COVID-19 pandemic began, the number of laboratories studying dangerous pathogens has increased dramatically in a global construction boom. By and large, the scientific community reacted to the new virus by building more labs to study potential plagues. As a result, this zero-sum debate is more pressing now than ever, because every new lab worker provides new opportunities for mishaps like accidental needle pricks, bites from infected lab rats, or broken air filtration systems.

Let’s revisit Black Saturday to learn, by analogy, about the grave risks posed by mishaps.

Black Saturday – When WWIII Almost Began Twice in One Day

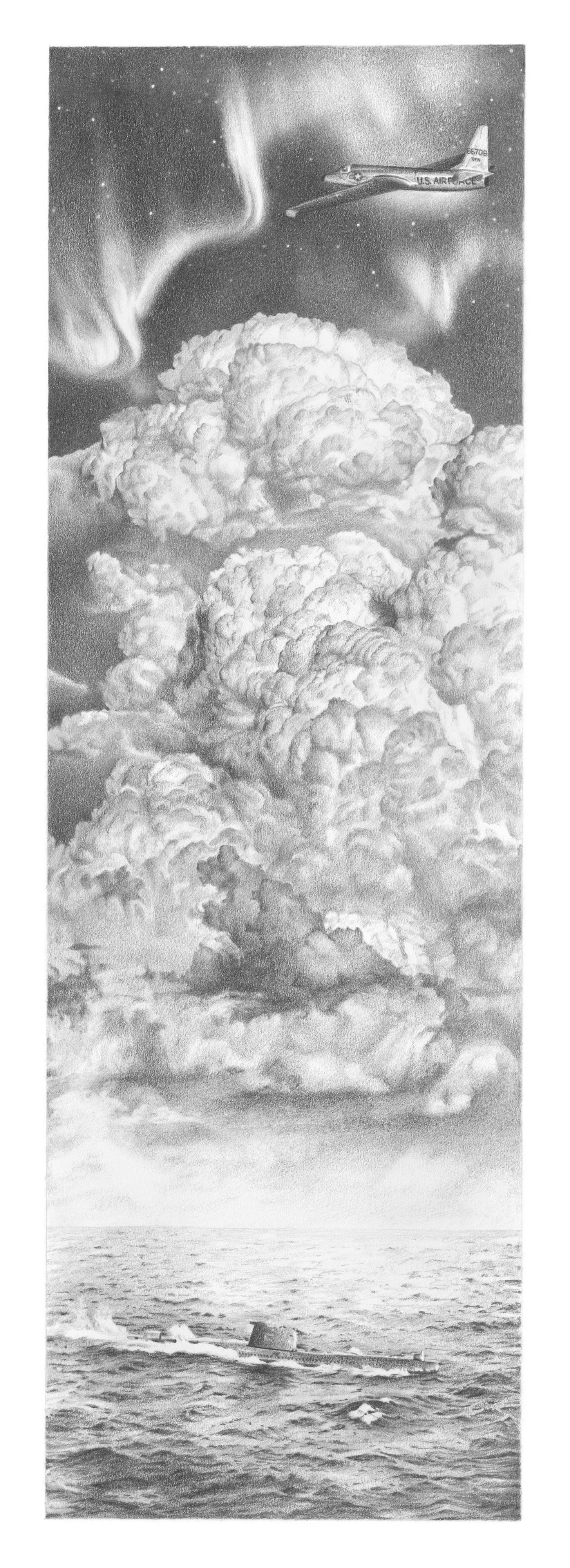

At midnight in Alaska, on Saturday, October 27, 1962, an American U-2 spy plane took flight. This lightweight craft soared high enough to reach the “coffin corner" where thin air could barely support the delicate plane, and it was ever at risk of breaking apart if it went slightly too fast. To achieve loftier heights than heavier craft, the U-2 lacked modern equipment, like a navigation system, that would weigh it down. So Captain Charles “Chuck" Maultsby navigated the romantic way, with a sextant and star charts, with which he tried to triangulate his position by the bright starlight of Arcturus, Vega, and Polaris (the North Star). Orion the Hunter should have crouched behind him.

Captain Maultsby was a pilot for Project Star Dust. His mission was to sample clouds above the North Pole with special filter paper and a Geiger counter, searching for evidence of nuclear weapons testing that would expel radioactive particles far outside Soviet airspace. But on that night, the dancing lights of an aurora borealis blotted out the stars. Celestial navigation failed him. His spy plane wandered over Russia, where Soviet interceptor jets hunted him down while the enemy tried to lure him closer by impersonating American radio operators – it was only by picking up music from a civilian radio station and flying away from the sound of Russian balalaikas that Captain Maultsby was able to right his course.

Alaskan Air Command ordered a pair of F-102 supersonic interceptor aircraft to find and protect Captain Maultsby's spy plane. But consider the options available to the F-102s if they encountered Soviet jets. This emergency played out against the backdrop of the Cuban Missile Crisis. Because the Pentagon was in a state of high alert, earlier that week it had ordered technicians to remove all conventional weapons from the F-102s and replace them with nuclear-tipped Falcon air-to-air missiles. If the Americans planes confronted the Soviet jets, then they could only defend themselves with nuclear weapons.

All told, Captain Maultsby stretched his waning fuel supplies for a record-breaking 10hr 25min flight by shutting down his engines and gliding back toward Alaska. Eventually the F-102s found and escorted him home. But had the Soviets met them in the air, there could have been nuclear war, and we would remember October 27, 1962, as the beginning of WWIII. When Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev withdrew from Cuba the next day, he privately complained to President Kennedy, “One of your planes violates our frontier during this anxious time we are both experiencing when everything has been put into combat readiness. Is it not a fact that an intruding American plane could be easily taken for a nuclear bomber, which might push us to a fateful step?” Humanity is fortunate that Captain Maultsby was an impressive and experienced pilot with enough wit to evade Soviet trickery and enough bravery to cut his engines at 70,000 feet.3

Meanwhile, in the subtropical Sargasso Sea near Cuba, on Saturday, October 27, 1962, the temperature inside Soviet Submarine B-59 was 113 degrees Fahrenheit in the coolest compartments. The Foxtrot class submarine was designed and insulated for Arctic waters; worse, saltwater had contaminated its diesel cooling system. Where the sub was warmed over by its engines, temperatures reached 140 degrees.

Multiple mechanical systems were failing,4 and only emergency lights functioned. The men were rationed a single cup of fresh water per day from limited reserves. Oxygen was running out, and as the air turned into a deadly cocktail of carbon dioxide, hydrogen, and methane, the crew showed signs of hypoxia: lethargy, confusion, nausea, headache, trouble breathing. In the dark and lonely submarine, many crewmembers fainted5 while everyone still conscious suffered from nasty skin rashes brought on by heat and filth. Captain Valentin Savitsky had lost contact with Moscow.6

While the B-59 crew suffered maddening conditions, an American destroyer tried to make the sub surface by dropping “practice” depth charges to signal it. These low-power explosives were not intended to damage the sub – but they were loud. “They exploded right next to the hull. It felt like you were sitting in a metal barrel, which somebody is constantly blasting with a sledgehammer,” recounted the B-59’s communications specialist Vadim Orlov, before claiming that this provocation caused his exhausted captain to ready a nuclear torpedo7 and shout:

Maybe the war has already started up there, while we are doing summersaults here! We’re going to blast them now! We will die, but we will sink them all – we will not disgrace our Navy!

Orlov credited second-in-command Vasili Arkhipov with calming their captain and preventing the strike. Rather than firing a nuclear torpedo, the B-59 surfaced and tensions with the Americans diffused. Humanity is fortunate that in the Soviet crew’s undersea inferno, a single cool head prevailed.

It takes little imagination to contemplate how Black Saturday could have unraveled rather than diffused.

Had the great power struggle between the U.S. and the U.S.S.R. not been at its climax, then this series of mishaps would have had far less potential to trigger WWIII. Malice indisputably caused the underlying instability festering that day. However, malice alone was insufficient to bring about Black Saturday, because neither the U.S. nor the U.S.S.R. wanted their cold war to heat up. Consider again Khrushchev’s complaint to Kennedy that the spy plane's mishap could have caused the “fateful step.” It would be foolish to underestimate the power of happenstance and error to shape tragedy.

Though banal, this lesson has always challenged humanity. We convince ourselves that we are more competent than our past validates. Like Ozymandias,8 even the best of us holds but tenuous control over our unwieldy fates.

The Easiest Lesson To Forget

Some scientists conducting research on deadly pathogens are poor students of this history lesson. Because they underestimate the power of happenstance and error to shape tragedy, when their prerogative to tinker with the most fearsome viruses and bacteria is challenged, they insist that the risks are worth it. However, their justifications are largely theoretical.

For example, in an infamous 2011 experiment, virologists intentionally enhanced the H5N1 strain of bird flu – which kills over half the people it infects – to become an airborne contagion among mammals.9 Maybe this research could have helped us better understand how to cope with H5N1 naturally evolving into an even more threatening form. But by 2022, when a new strain of H5N1 did become transmissible among mammals in nature, our only recourse was slaughtering 50,000 exposed minks and mourning the 700 dead sea lions that washed up across the shores of Peru.10

The risky research provided no new solutions despite a decade-long head start. Meanwhile, between 2012 and 2014, the same virologists who enhanced H5N1 in their University of Wisconsin lab reported at least ten different lab accidents in just two years. After one high-profile needle prick exposed a researcher to H5N1, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) reprimanded the lab for bungling biosafety procedures rather than adequately protecting the public when the scientist was exposed.11

Ron Fouchier is one of the leading virologists who enhanced this deadly avian flu, and he defends his research in grandiose terms. In a 2023 interview he declared, “If you stop this research, you surrender to the next pandemic.” This frames his passion project as an essential bulwark against existential threat. But his experiments have yet to offer tangible means of preventing or mitigating an H5N1 pandemic; instead, he has only given that virus new opportunities to spread among us. Fouchier underestimates the power of happenstance and error to shape tragedy.

Humbler scientists were so alarmed by Fouchier and his colleagues’ tinkering with H5N1 that the scientific community became embroiled in a debate about biosafety. Ever since, experts have been arguing over the merits of experiments like Fouchier’s. This controversy spread into the public sphere once laypeople started to wonder if the COVID-19 pandemic began in a Wuhan lab. But that question should not distract from the underlying problem: Even if we never definitively learn how COVID-19 emerged, we already know that laboratory accidents with potential pandemic pathogens pose a threat to human life that is outsized relative to theoretical benefits.

In 2022, the esteemed virologist Jesse Bloom made “A Plea for Making Virus Research Safer" in the New York Times:

I am a virologist who studies how mutations enable viruses to escape antibodies, resist drugs and bind to cells. I know virology has done much to advance public health. But a few aspects of modern virology can be a double-edged sword, and we need to promote beneficial, lifesaving research without creating new risks in the lab.

Bloom has this to say about the H5N1 experiments performed by Fouchier and his colleagues:

The National Institutes of Health funded two research groups to increase the transmissibility of an earlier strain of avian influenza that had killed hundreds of people but could not efficiently spread from person to person. Both groups created viral mutants that could transmit in ferrets. The Obama administration was so alarmed that it halted gain-of-function work on potential pandemic influenza viruses in 2014, but the N.I.H. allowed it to restart by 2019.

In my view, there is no justification for intentionally making potential pandemic viruses more transmissible. The consequences of an accident could be too horrific, and such engineered viruses are not needed for vaccines anyway.

After enumerating other types of research that are not worth the risk, like synthetically reconstructing extinct pandemic pathogens to study what made them so deadly, Bloom concludes:

Overall, most virology research is safe and often beneficial. But experiments that pose pandemic risks should be stopped, and other areas require continued careful assessment. Several groups are developing frameworks for oversight and regulation.

But who should ultimately decide?

Some virologists think we should have the final say, since we’re the ones with technical expertise. I only partially agree. I’m a scientist. My dad is a scientist. My wife is a scientist. Most of my friends are scientists. I obviously think scientists are great. But we’re susceptible to the same professional and personal biases as anyone else and can lack a holistic view.

The French statesman Georges Clemenceau said, “War is too important to be left to the generals.” When it comes to regulating high-risk research on potential pandemic viruses, we similarly need a transparent and independent approach that involves virologists and the broader public that both funds and is affected by their work.

In ancient Rome, there were slaves tasked with repeating “memento mori” in the ears of generals celebrating victory. In contrast to the cheering crowd, the slave's whispered wisdom was meant to keep the general humble.

Like a general who feels invincible after conquering a mighty foe, a virologist might find it hard to believe that he could lose control over the virus he so deftly manipulates — especially when their wild experiments earn them prestige, funding, and fame within their field.

Who will remind the scientists who soup up pathogens that the easiest history lesson to forget is beware hubris?

Mutually Assured Disease

We should also remind these reckless scientists of Mark Twain’s quip that, “History doesn’t repeat itself, but it often rhymes.” Just as a series of mishaps nearly triggered nuclear war on Black Saturday, lab accidents could cause a pandemic more devastating than COVID-19. At least that plague largely spared children.

Here’s another way that the history of biolabs rhymes with the history of atom bombs:

Smallpox is the only disease humanity has ever eradicated… for the most part. It still exists in cold storage, like a zoo animal whose species went extinct in the wild. It lives on in the U.S. Center for Disease Control (CDC) lab in Atlanta, Georgia, and in the Russian Vector Institute for Virology in Novosibirsk, Siberia. The logic for keeping smallpox is reminiscent of Mutually Assured Destruction: if they have it, then we need it too, just in case a bad actor harnesses smallpox for a bioweapon. We might need our own samples to develop new vaccines and anti-viral drugs.

Dr. Kanatjan Alibekov defected from the ruins of the Soviet Union in 1992 and made a break for New York City. He was the former second-in-command of the Soviet biological weapons program. After Bill Patrick from the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) debriefed Alibekov, he said, ''It scared the hell out of me when I first talked to this fellow.”

Alibekov, who gained U.S. citizenship and shortened his name to Ken Alibek, cautioned his new country that Russian bioweapons research was surely continuing despite official claims that the program had been shuttered. Perhaps more worrisome, in an interview with the New York Times in 1998, Alibek warned that “terrorist groups and rogue states” could have bioweapons because some of his former Soviet colleagues may be working “for the highest bidder.” So the U.S. stores smallpox in Atlanta because Putin, terrorists, or rogue states might use smallpox samples to create a bioweapon.

Harnessing disease for mass destruction is dangerous for the attacker, too. Few people nowadays have any immunity to smallpox, so a plague that starts anywhere can quickly spread everywhere, burning through an immunologically naïve population. The logic of nuclear deterrence involves the threat of retaliatory strikes, but weaponized smallpox might be more like murder suicide.

In July 2014, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) discovered six vials of smallpox virus in unsecured cardboard boxes stashed in the back left corner of its laboratory’s cold storage room in Bethesda, Maryland. One of the most menacing viruses to ever exist had sat there for decades unbeknownst to any current laboratory staff amidst 321 other orphaned vials.12 The FDA estimated that the vials were prepared sometime between 1946-1964, but it cannot determine who created them or why they were stored in that room.13

No one was infected in this incident. But, there will always be new opportunities for happenstance and error to shape tragedy.

Artificial intelligence is a more popular contender for this title. I'd wager that its risks are more theoretical compared to the immediate concerns posed by research on deadly pathogens. But even if you disagree — why not both?

Investigative reporter Alison Young made a comprehensive report of this problem in her 2023 book Pandora's Gamble: Lab Leaks, Pandemics, and a World at Risk.

My re-telling of this event is drawn from One Minute to Midnight: Kennedy, Khrushchev, and Castro on the Brink of Nuclear War, by Michael Dobbs. You can read an excerpt from his book here to learn more details about this frightful night.

More details are available in the account of Vice-Admiral Vasili Arkhipov, who was second-in-command of Submarine B-59.

“They were falling like dominoes.” — from the recollections of Submarine B-59’s communications specialist Vadim Orlov.

The Americans were unaware that the Soviet sub was armed with a nuke.

Percy Bysshe Shelley's short poem about hubris is worth quoting in full:

I met a traveller from an antique land,

Who said—“Two vast and trunkless legs of stone

Stand in the desert. . . . Near them, on the sand,

Half sunk a shattered visage lies, whose frown,

And wrinkled lip, and sneer of cold command,

Tell that its sculptor well those passions read

Which yet survive, stamped on these lifeless things,

The hand that mocked them, and the heart that fed;

And on the pedestal, these words appear:

My name is Ozymandias, King of Kings;

Look on my Works, ye Mighty, and despair!

Nothing beside remains. Round the decay

Of that colossal Wreck, boundless and bare

The lone and level sands stretch far away.”

They used ferrets because they are one of the best animal proxies for humans, so this enhanced flu virus was specifically designed to target human-adjacent lungs.

I discussed this troubling research in more depth (and told “A Brief History of Lab Leaks") in my previous essay about the lab leak theory of COVID-19 origins:

At the time of writing, the Wisconsin legislature is debating a new bill that would regulate this kind of research in their state. Scientists from the advocacy group Biosafety Now testified in support of the bill.

Nine other vials could not be identified by their aged labels.

Nuclear weapons have also been stored improperly, such as the embarrassing “Minot incident” in 2007 when six nukes were misplaced for 36hr. The AirForce Times called this "one of the Air Force’s biggest black eyes, and led to the unprecedented, simultaneous firing of the then-secretary and chief of staff.”