What If I'm Wrong?

Part 2

An earlier version of this essay first appeared in Areo Magazine on July 19, 2019. Here it is adapted as a visual essay.

Please read the first installment in this two-part visual essay here.

In Part 1, I claimed that curiosity is sacred because it can uniquely soothe the discomfort of experiencing doubt. If we genuinely want to understand the world as it really is, then we must doubt even the ideas we hold dear. Otherwise, wishful thinking distorts the truth.

So in the spirit of this conviction, I wonder: What if I'm wrong?

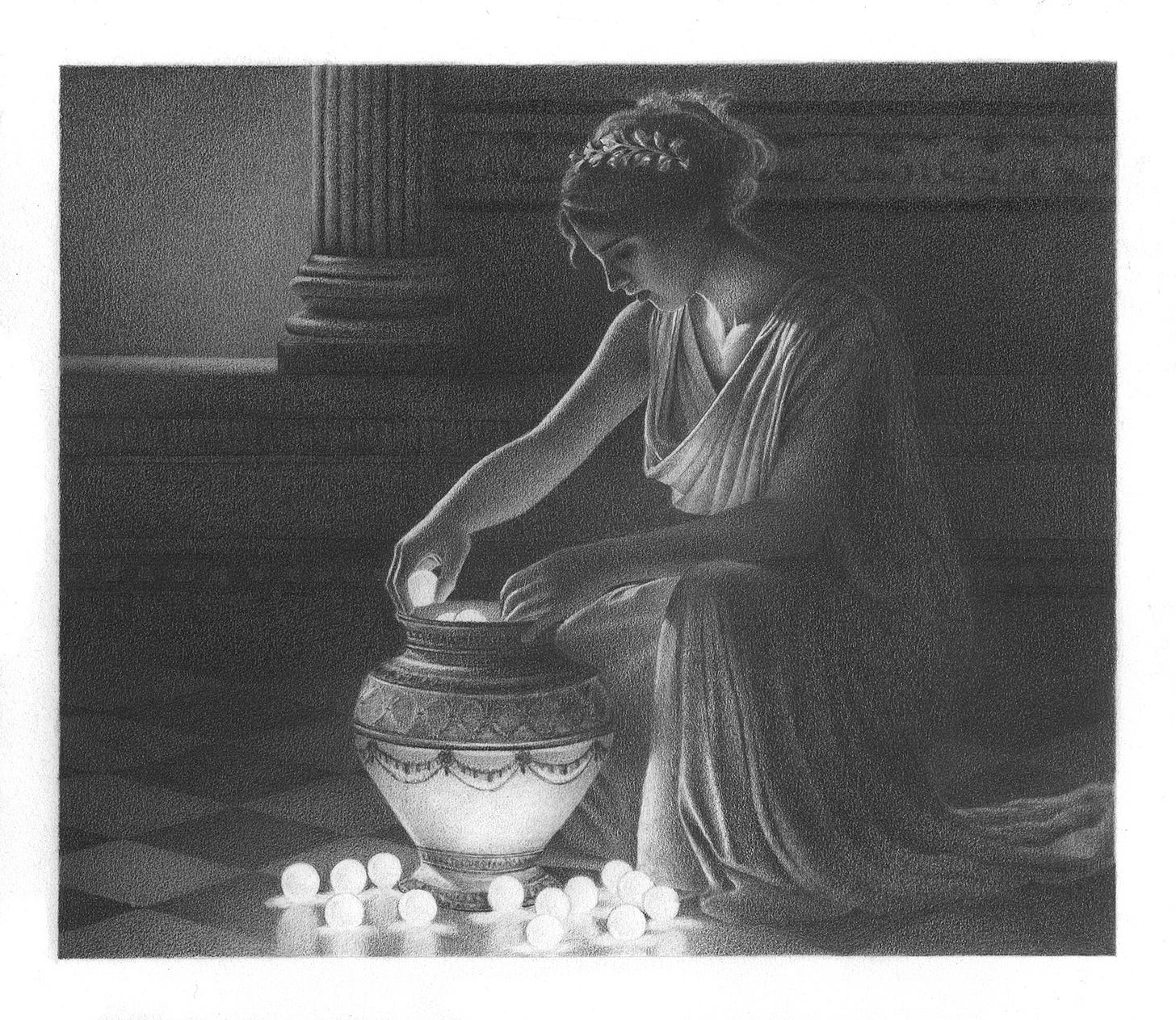

The most extreme way that curiosity might betray us resembles the Pandora myth. In that story, Zeus punished Prometheus for giving humanity the gift of fire to enable progress. Then he punished humanity for accepting enlightenment by giving Pandora a jar full of horror and evil and imbuing her with curiosity so that she was bound to open it.

A philosopher of existential risk has updated the Pandora myth for the 21st century. Nick Bostrom, the Founding Director of the Future of Humanity Institute at Oxford University, posits The Vulnerable World Hypothesis: “roughly, one in which there is some level of technological development at which civilization almost certainly gets devastated by default.” Bostrom explains his hypothesis using the metaphor of “the urn of possible inventions,” and the implications are far more tragic than Pandora's jar:1

One way of looking at human creativity is as a process of pulling balls out of a giant urn. The balls represent possible ideas, discoveries, technological inventions. Over the course of history, we have extracted a great many balls — mostly white (beneficial) but also various shades of gray (moderately harmful ones and mixed blessings). The cumulative effect on the human condition has so far been overwhelmingly positive, and may be much better still in the future. The global population has grown about three orders of magnitude over the last ten thousand years, and in the last two centuries per capita income, standards of living, and life expectancy have also risen.

What we haven’t extracted, so far, is a black ball: a technology that invariably or by default destroys the civilization that invents it. The reason is not that we have been particularly careful or wise in our technology policy. We have just been lucky.

…

What if there is a black ball in the urn? If scientific and technological research continues, we will eventually reach it and pull it out. Our civilization has a considerable ability to pick up balls, but no ability to put them back into the urn. We can invent but we cannot un-invent. Our strategy is to hope that there is no black ball.

If Pandora were to pull a black ball out of the urn of possible inventions, then humanity would not merely suffer — we would end.

A key example of a gray ball was learning how to split the atom. While nuclear power plants offer abundant energy with a small carbon footprint, nuclear bombs are the most fearsome weapons ever invented. Bostrom pairs his metaphor about the urn of possible inventions with a thought experiment: what if it was quite easy to make a nuclear bomb? If nukes had been simple to build, then the kind of men prone to become mass shooters or terrorists would be able to assault all of humanity nearly instantaneously. In that counterfactual, nuclear power would be a black ball.

Inventions like nuclear fission begin with a curious person wondering how the world works. Physicists become physicists because they want to comprehend the fundamental laws of nature. They yearn to understand the mystery of existence. This is such a romantic pursuit that it seems incongruous that it could begin a chain reaction ending in Armageddon. Is curiosity a Trojan horse?

My argument that curiosity is sacred builds on physicist Richard Feynman’s speech “The Value of Science,” which he gave after grappling with the psychological fallout of helping to invent the atom bomb. After the Manhattan Project, Feynman slumped into depression. If he walked past a construction site, he thought it foolish. Why build anything new in a doomed world? He wondered:

What is the value of the science I had dedicated myself to — the thing I loved — when I saw what terrible things it could do? It was a question I had to answer.

Feynman concluded that we derive value from science by learning how doubt is not to be feared but welcomed and discussed. He believed that science could instill a satisfactory philosophy of ignorance that made freedom of thought possible. Science, and the curiosity that drives it, has value because it is the most reliable way to learn the truth.

But Nick Bostrom challenges the fundamental assumption:

…that truth is good, more truth is better, finding out and disseminating truth and explaining truth is always and everywhere a good and should be encouraged as much as possible. And that’s actually a non-obvious assumption if you start to think about it. It might be that the net effect of being more open to free investigation over the last few hundred years has been vastly beneficial, on balance, but just how strong evidence is there that this will continue to be true into the indefinite future?

If there is a black ball in the urn of possible inventions, then discovering that truth would be a bad thing. In the fullness of time, curiosity might damn humanity.2

Worse, the only solution Bostrom can imagine for preventing us from pulling out a black ball is totalitarian surveillance. In a scenario where anyone could easily create a newly discovered doomsday device, he imagines a “high-tech panopticon” that watches everyone and puts a stop to suspicious behavior. Bostrom is hardly enthusiastic about totalitarianism, and he invokes George Orwell to forthrightly express that his only idea for staving off extinction in a vulnerable world is horrifying.

Feynman comforted himself that curiosity and science were still valuable because they could enable freedom of thought — and that is exactly what Bostrom worries about. If we stalwartly declare with Patrick Henry, “Give me liberty, or give me death!” then our fate may well be the latter. When a single deranged individual could initiate a murder-suicide affecting all of humanity, does liberty become overindulgent?

The Vulnerable World Hypothesis is a vexing conundrum that pits truth and freedom of thought against survival. I have another doubt that curiosity is sacred, which is separate from Bostrom’s theory but also compounds it.

My entire premise for sacralizing curiosity may be naïve. I argued that we can learn humility from curiosity if it ennobles us to admit what we do not know. And though I acknowledged that this process is not guaranteed, what if curiosity rarely humbles us?

Consider how the scientific community punished astronomer Carl Sagan for popularizing science in easily understood terms. His story suggests that scientists are deficient in humility, even though they are professionally curious. When science writer Michael Shermer interviewed Jared Diamond about being both a scientist and a popular author, their conversation turned toward Sagan, and Diamond explained:

You mentioned Carl Sagan as, perhaps implicitly, an example of a person who got away with it — who wrote for the public but nevertheless who was respected by scientists. Carl Sagan is actually notorious, because [he] is one of the few American scientists during my lifetime in the National Academy of Sciences who was de-elected… Members of the National Academy challenging his nomination said things like, “He has a pretty face, but what has he ever done for science?”

On the one occasion that I met him… a reporter asked him, “Have you ever taken flack for writing for the public?” I gasped, and those of us who knew what happened gasped, because we were afraid that he would say, yeah, I got de-elected from the NAS. But he said, “No, not really.”

[Scientists] scorn explaining [their findings] to the broader public, and regard explaining it to the public as prostituting yourself.

Harvard University may have denied Sagan tenure on similar grounds. Like Zeus, Sagan’s peers meted out punishments to someone who tried to teach humanity how the world works.

If anyone has embodied the virtues of making curiosity sacred, it was Carl Sagan. As he evangelized wonder, Sagan discussed the wounds science has inflicted on human pride, most famously in his speech about how every person, whether grand or obscure, has shared our pale blue dot. He urged us to shed our provincial vantage point by considering a photo taken by the Voyager 1 spacecraft from the edge of our galaxy, where Earth looks like a mote of dust suspended in a sunbeam. “Think of the rivers of blood spilled by all those generals and emperors, so that in glory and triumph they could become the momentary masters of a fraction of a dot.” For Sagan, astronomy was a humbling and character-building experience because it helped visualize the narcissism of our small differences.

Sagan demonstrated his strength of character by magnanimously declining to speak ill of his colleagues in the NAS. They were wrong to say that his contribution to science was no more than a pretty face. Their disdain for communicating clearly with laypeople was shameful. The snobbish streak in the scientific community suggests that curiosity too often coexists with arrogance. How worried should we be that an arrogant scientist is more likely to act cavalier about pulling a black ball out of the urn of possible inventions?3

There is no recipe for wisdom. Paradoxically, we should be inquisitive enough to ask how being inquisitive could unleash horror and evil into the world, like opening Pandora’s jar. The Vulnerable World Hypothesis is a uniquely troubling answer to that line of inquiry; if correct, it poses an intractable problem. Should we agree with Socrates that, “The unexamined life is not worth living,” and continue our current strategy of hoping there are no black balls in the urn? Or do we shackle ourselves to the possible shelter of totalitarianism?

Carl Sagan also worried about our vulnerable world:

There are not yet obvious signs of extraterrestrial intelligence, and this makes us wonder whether civilizations like ours rush inevitably into self-destruction. I dream about it... and sometimes they are bad dreams.

Has another civilization, on a far-away mote of dust suspended in an alien sunbeam, already pulled a black ball out of the urn of possible inventions?

Though popularized as “Pandora's box,” in the original Greek myth Pandora was given a jar.

💛💛 loved this