When Art Became a Joke

It's not funny if I have to explain it.

“Those who bought it, what kind of people are they?” he asked. “Do they not know what a banana is?”

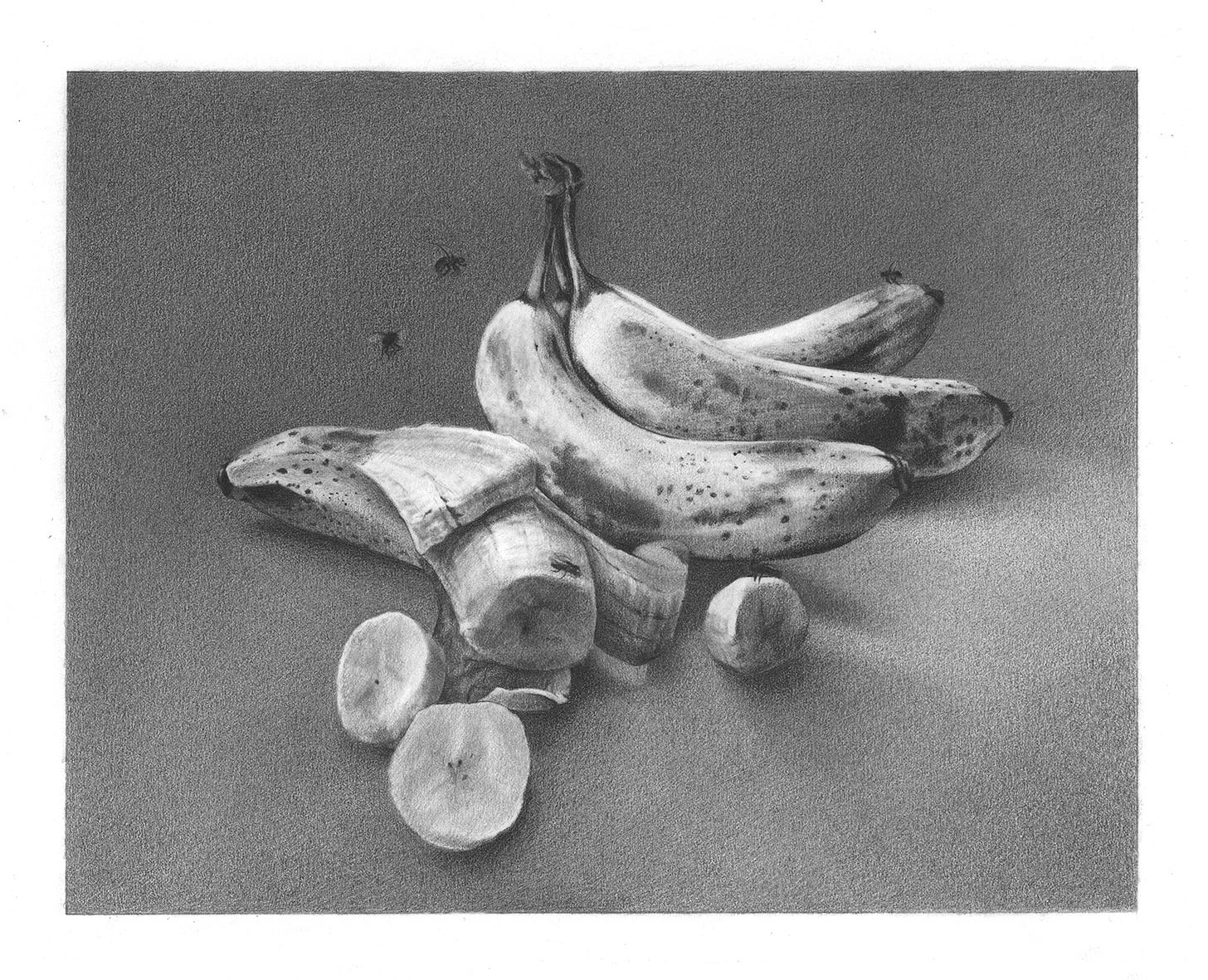

After Maurizio Cattelan’s artwork titled “Comedian” — better known as the infamous duct-taped banana — sold for $6.2 million at Sotheby’s last November, the New York Times tracked down the old man who sold the fateful banana at a sidewalk fruit stand outside of the auction house. Nearly blinded by cataracts, the Bangladeshi immigrant is no longer able to enjoy visual art. The story seems crafted by God himself to guilt trip the progressive art world for the meretricious spectacle of its conceptual art:

At the fruit stand where he works on Manhattan’s Upper East Side, Shah Alam sells dozens of bananas a day at 35 cents a piece, or four for a dollar. He does a brisk business in cheap fruit outside Sotheby’s auction house; inside, art can sell for millions.

But last Wednesday, Mr. Alam sold a banana that a short time later would be auctioned as part of a work of absurdist art, won by a cryptocurrency entrepreneur for $5.2 million plus more than $1 million in auction-house fees.

A few days after the sale, as Mr. Alam stood in the rain on York Avenue and East 72nd Street, snapping bananas free of their bunches, he learned from a reporter what had become of the fruit: It had been duct-taped to a wall as part of a work by the Italian artist Maurizio Cattelan, and sold to Justin Sun, the Chinese founder of a cryptocurrency platform.

And when he was told the sale price, he began to cry.

“I am a poor man,” Mr. Alam, 74, said, his voice breaking. “I have never had this kind of money; I have never seen this kind of money.”

Elsewhere in the Times, back in 2019 when “Comedian” debuted at Art Basel Miami Beach, critic at large Jason Farago offered “A (Grudging) Defense of the $120,000 Banana.” He takes pains to soothe the predictable sting felt by the common man (or at least, Times readers of art criticism who are concerned about the common man) upon learning the eye-watering price that a browning banana fetches once an artist like Cattelan tapes it to a gallery:

Well, is it art? Is Mr. Cattelan taking us for a ride? Did you have to be there? Isn’t this banana just a banana, and not a wry commentary on male sexuality, genetic monocultures, or Central American geopolitics? (I am sparing you a lecture on the Guatemalan coup d’état of 1954, and the origin of the phrase “banana republic”….)

Let me reassure you, you are not a hopeless philistine if you find this all a bit foolish. Foolishness, and the deflating sensation that a culture that once encouraged sublime beauty now only permits dopey jokes, is Mr. Cattelan’s stock in trade.

But Farago’s words offer little comfort to the old man who sold the banana. We learn in the Times that “To Mr. Alam, the joke of ‘Comedian’ feels at his expense. As a blur of people rushed by his corner a few days after the sale, shock and distress washed over him as he considered who profited — and who did not.” The artist, for his part, told the reporter that “The reaction of the banana vendor moves me deeply, underscoring how art can resonate in unexpected and profound ways… However, art, by its nature, does not solve problems — if it did, it would be politics.” Despite his reputation as a provocateur, Cattelan is not cruel enough to give Mr. Alam the more pointed and pretentious response: “Of course I know what a banana is, the problem is that you don’t understand art.”

And though Cattelan stands to gain from any attention, Farago is exasperated to rehash the debate that Marcel Duchamp began over a century ago when he became the father of contemporary art by perching a urinal on a gallery pedestal — an act that, in the fullness of time, unleashed conceptual art like Cattelan’s upon the world:

I don’t have much good to say about the random guy who munched Mr. Cattelan’s banana, though it continues a long tradition of literalists who like bringing conceptual art from the realm of ideas back down to Earth. Numerous artists have relieved themselves in “Fountain,” Marcel Duchamp’s upturned urinal; John Lennon, in 1966, notoriously picked up an apple in Yoko Ono’s first London exhibition and took a bite. And thus they met.

For when it comes to the banana’s ontological status as art or produce, I thought we had settled this already. If you buy a light work by Dan Flavin and the fluorescent bulb starts flickering, you can replace it with a new one. If you buy a Sol LeWitt wall drawing and you move house, you can erase the old one and draw a new one. A banana, even more than a light fixture, was always going to require replacement; Mr. Cattelan had already drawn up instructions for the lucky collectors to replace the fruit every week to 10 days (“Everybody changes flowers regularly,” his dealer Emmanuel Perrotin observed.)

Throughout the review, Farago’s tone is reminiscent of Arthur Danto, a philosopher of aesthetics who preferred his art within the realm of ideas. Danto was influential in updating the definition of “art” to incorporate the most avant-garde twentieth century creations. Toward the end of his life, around the turn of the twenty-first century, Danto hesitantly began to defend beauty in an art world that had long since grown embarrassed by it — all while clinging to his love of Duchamp, no matter how much damage that original art prankster did to the art world’s valuation of beauty. The philosopher tried to gently reintroduce beauty into the art world like returning an endangered species to its original habitat.

“Foolishness, and the deflating sensation that a culture that once encouraged sublime beauty now only permits dopey jokes, is Mr. Cattelan’s stock in trade.”

Danto was also a bit tired of discussing Duchamp’s “Fountain” by the time he published The Abuse of Beauty in 2003, at nearly 80 years old. But the topic is inescapable, because that urinal marked the moment when the art world began devaluing beauty. Danto sees “Duchamp as the artist who above all has sought to produce an art without aesthetics, and to replace the sensuous with the intellectual,” and writes that Duchamp’s break with beauty was so radical that it was incomprehensible to his own supporters:

Consider, for illustrative purposes, the notorious example of Marcel Duchamp’s perhaps too obsessively discussed “Fountain,” which, as by now everybody knows, largely consisted of an ordinary industrially produced urinal. Duchamp’s supporters insisted that the urinal he anonymously submitted to the Society of Independent Artists in 1917 was meant to reveal how lovely this form really was – that abstracting from its function, the urinal looked enough like the exemplarily beautiful sculpture of Brancusi to suggest that Duchamp might have been interested in underscoring the affinities. It was Duchamp’s patron, Walter Arensberg, who thought — or pretended to think — that disclosing the beauty was the point of “Fountain” — and Arensberg was a main patron of Brancusi as well.

Now Duchamp’s urinal may indeed have been beautiful in point of form and surface and whiteness. But in my view, the beauty, if indeed there, was incidental to the work, which had other intentions altogether. Duchamp, particularly in his readymades of 1915-1917, intended to exemplify the most radical dissociation of aesthetics from art. “A point which I very much want to establish is that the choice of these ‘readymades’ was never dictated by aesthetic delectation,” he declared retrospectively in 1961. “The choice was based on a reaction of visual indifference with at the same time a total absence of good or bad taste . . . in fact a complete anesthesia.” Still, Duchamp’s supporters were aesthetically sensitive persons, and though they may have gotten his intentions wrong, they were not really mistaken about the fact, incidental or not, that the urinal really could be seen as beautiful. And Duchamp himself had said that modern plumbing was America’s great contribution to civilization.

But why dissociate aesthetics from art? While many of Duchamp’s peers were disillusioned with humanity — the Dada movement that Duchamp closely associated with reacted to the horrors of World War I, and then after WWII, the philosopher Theodore Adorno declared that “Writing poetry after Auschwitz is barbaric”— Duchamp himself was not preoccupied with social and political issues. Yet by instigating the devaluation of beauty, Duchamp aided and abetted every subsequent art trend benefitting from aesthetic indifference.

But even before the trauma of two world wars, a new technology had already upended the purpose of visual art. Duchamp challenged beauty at a moment in history when photography had just come into its own as a medium. Through the efforts of photographers like Alfred Stieglitz (who married his muse, the painter Georgia O’Keeffe, and photographed her extensively), this new means of making images gained recognition as a legitimate art form. In the decades leading up to Duchamp’s first readymade provocation, photographers like Stieglitz had been putting up gallery shows that mingled photography and painting together to legitimize the new medium by placing it alongside tradition.

Paintings recorded history until photography began to document reality more faithfully. Shorn of this task, by the early 1900s artists were dissecting the very nature of painting to analyze its component parts and discover its modern purpose. The Cubists would view a scene from many perspectives all at once, merging myriad vantage points in space and time — whereas photographic film could not be repeatedly exposed enough to create so many overlapping viewpoints. Wassily Kandinsky, the father of abstraction, turned color into his religion; other early abstract painters like Piet Mondrian declared that “Art should be above reality, otherwise it would have no value for man,” then distilled the formal elements of a painting into only primary colors and simple, geometric shapes. And conceptual art, beginning with Duchamp, extracted the ideas out of painting.

This led to the central question of Danto’s career as a philosopher of aesthetics:

The issue of defining art became urgent in the twentieth century when art works began to appear which looked like ordinary objects, as in the notorious case of Marcel Duchamp’s readymades. As with the Brillo boxes of Andy Warhol and James Harvey, aesthetics could not explain why one was a work of fine art and the other not, since for all practical purposes they were aesthetically indiscernible: if one was beautiful, the other one had to be beautiful, since they looked just alike. So aesthetics simply disappeared from what Continental philosophers call the “problematic” of defining art.

In The Abuse of Beauty, Danto pairs Duchamp’s irreverence with Adorno’s pessimism: “It is self-evident that nothing concerning art is self-evident any more, not its inner life, not its relation to the world, not even its right to exist.” And despite that these two giants of twentieth century artistic thought were very different kinds of men — Adorno was grim, while Duchamp was impish — they do go well together. Both viewed beauty with suspicion.

The philosopher tried to gently reintroduce beauty into the art world like returning an endangered species to its original habitat.

Crucially, Duchamp did not simply isolate ideas in visual art as a philosophical statement about the preeminence of concepts. He was pursuing just one idea: a total visual indifference that he called anti-art. He told a symposium at the Museum of Modern Art in 1961 that “I don’t want to destroy art for anybody else but myself” — but he overshot his goal. Adorno would have sounded less convincing in 1969 when he asserted that art no longer has a self-evident right to exist, if not for Duchamp’s activities decades earlier.

This is the artistic and philosophical heritage of Cattelan’s duct-taped banana. It is a history of irreverent gestures — plopping down a urinal, duct-taping a banana — that are taken so seriously by art critics that they contort the very meaning of art around their absurdity. Here is how Farago interprets “Comedian”:

Mr. Cattelan directs these barbs at art from inside the art world, rather than lobbing insults from some cynical distance. His entire career has been a testament to an impossible desire to create art sincerely, stunted here by money, there by his own doubts. …

Actually, real artists are not out to hoodwink you. What makes Mr. Cattelan a compelling artist… is precisely Mr. Cattelan’s willingness to implicate himself within the economic, social and discursive systems that structure how we see and what we value. It makes sense that an artist would find those systems dispiriting, and the duct-taped banana… might testify to his and all of our confinement within commerce and history. In that sense, the title “Comedian” is ironic — for Mr. Cattelan, like all the best clowns, is a tragedian who makes our certainties as slippery as a banana peel.

This generous interpretation raises more questions than it answers. Does commerce actually confine Cattelan, or has the art market emboldened his antics? Why is Cattelan’s alleged desire to create sincere art hampered by money and doubt — has he suffered more than Francisco Goya, who endured relentless illness and war, while fear of madness taunted his troubled mind? For decades around the turn of the nineteenth century, Goya was a court painter to the King of Spain, and while he was painting royal portraits, he also made etchings and paintings about “the innumerable foibles and follies to be found in any civilized society, and from the common prejudices and deceitful practices which custom, ignorance, or self-interest have made usual.” But back when Goya took on the role of tragedian, beauty was inseparable from art, and his ability to create beautiful images seduced viewers into engaging with Goya’s social critiques far longer than anyone scrolling through Instagram lingers on selfies with Cattelan’s duct-taped banana.

Till his death, Danto maintained “that beauty was no part of the concept of art, that beauty could be present or not, and something still be art.” At the same time, he eventually realized that “beauty is the only one of the aesthetic qualities that is also a value, like truth and goodness. It is not simply among the values we live by, but one of the values that defines what a fully human life means.” He tried to reconcile these beliefs by writing that “Beauty is an option for art and not a necessary condition. But it is not an option for life. It is a necessary condition for life as we would want to live it.”

But even if Danto is correct that beauty is only optional for art, we should think hard about whether humanity has benefited from what Duchamp and Cattelan have brought into the world. For to claim that artists can choose indifference to beauty is not to say that they should.

This is a fascinating and beautifully written essay.

The tragedy of Duchamp and others is that they were the ones who relegated art to such a sorry state, not art itself. Art, freed from the constraints of beauty, is purely didactic. And didacticism is better achieved through other media. This turn is likely responsible for the gross politicization of art in the past century, and its resulting dismissal by many. I think many people criticize Duchamp without properly understanding him, though there is a degree to which even the casual observer rightly observes that his readymades are mocking the audience. Observing such art feels like being scolded.

Plato thought that beauty and the Good were intimately connected. If we remove beauty from art, we may be foregoing the good inherent in art as well. Art which is nihilistic can hardly be said to cultivate virtue.

Thanks for this.