Where Do Works of Art Belong?

An Artist's Response to James Kierstead’s “The Elgin Marbles: Playing for Keeps"

This visual essay first appeared in Quillette on March 27, 2024.

It’s an offshoot of my ongoing series called Ideas Worth Drawing For, in which I make hand-drawn images to honor the excellence of essayists I admire. I regularly contribute visual essays to Quillette that spotlight pieces from the magazine’s archive.

If I told you [to] cut the Mona Lisa in half… do you think your viewers would appreciate the beauty of the painting?

Greek Prime Minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis offended his British counterpart when he described the situation with the Elgin marbles using that analogy, as if taken from the Judgement of Solomon in the Hebrew Bible.

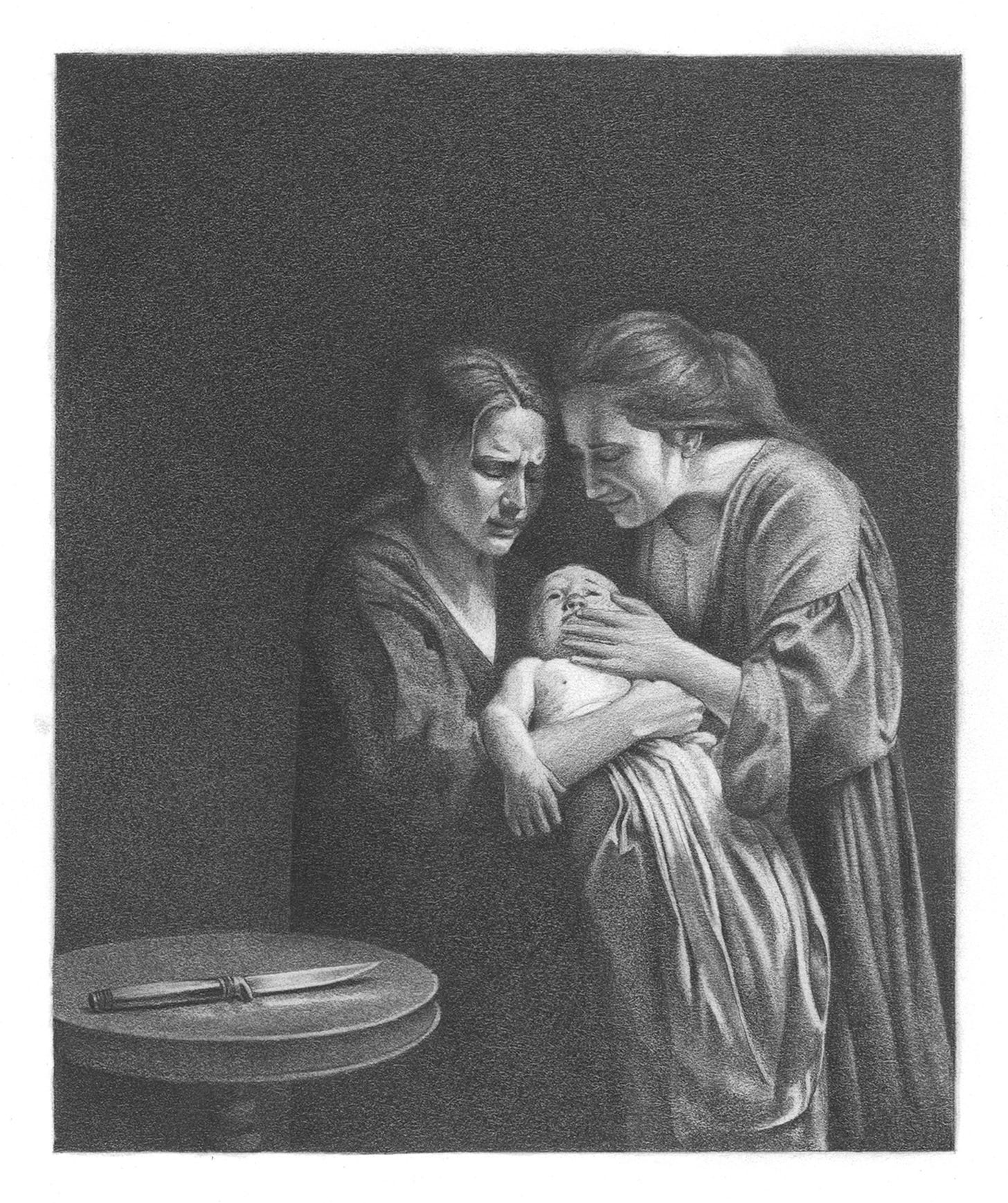

In the Bible story, two women both claim to be the mother of a newborn baby, and they ask King Solomon to decide who has the best claim to the child. Neither woman has witnesses or evidence to support her claim. So, King Solomon asks for a sword and pronounces, “Divide the living child in two, and give half to the one, and half to the other.” One woman begs him not to slay the baby, but to give it to her rival instead. The other woman declares, “It shall be neither mine nor thine, but divide it.” This ploy reveals the true mother. Rather than cut the baby in half, the wise king gave it to the woman who begged that its life be spared.1

So, who is the true mother of the Elgin marbles? Perhaps we need the wisdom of Solomon to decide.

Over 200 years ago, Thomas Bruce, the Seventh Earl of Elgin, removed over half of the surviving Parthenon sculptures from Athens. They have been on display in the British Museum for centuries. For almost as many years, Greece has been petitioning for their return. Whether the Earl of Elgin had permission to take the artefacts—and whether anyone actually had the right to give him that permission—is central to the argument between Britain and Greece.

In “The Elgin Marbles: Playing for Keeps,” classicist James Kierstead analyses “one of the longest-running and most contentious debates about the place of historical artefacts in a postcolonial world.” The movement to repatriate artwork has been gaining momentum. The American Museum of Natural History in Manhattan has just shut down two major exhibition halls because of new US regulations that forbid displaying or researching Native American artifacts without explicit permission from native tribes. Kierstead’s piece helps us make sense of these debates.

Though people often try to lay claim to the past, no one alive today is part of the culture that built the Parthenon almost 2,500 years ago. Since that time, many cultures have repurposed the temple. In the fifth century, Christians converted the Parthenon into a church, and it remained as such for almost a thousand years, during which time it became a hugely important pilgrimage site. Then, when the Ottoman Turks invaded in the fifteenth century, they turned it into a mosque, which they later used to store gunpowder during their war with the Venetians. A Venetian cannonball blew up the Parthenon powder keg in 1687.

Over the course of millennia, the Parthenon has been modified, defaced, looted, burned down, and blown up. The Earl of Elgin was a latecomer to this historical trajectory, and his fear for the safety of the marbles may have contributed to his decision to remove more than half of them. After all, a local had told him that some of the statues had already been burned for lime to make mortar for new buildings.

Even if Elgin thought he was taking the marbles for safekeeping, in doing so, he too endangered them. As Kierstead notes, “In 1802, one of the first ships transporting the marbles sank off the island of Kythira and its cargo had to be recovered by sponge-divers.” He adds:

Some of the sculptures Elgin left on the Parthenon did subsequently disappear or were damaged by Athens’ polluted air; but the marbles he brought to London also suffered damage, both from London’s air pollution and from a series of controversial attempts to clean them. And while it’s true that a cash-strapped Greek state often struggles to take proper care of its huge and varied inheritance of artefacts and remains, no one now seriously doubts that Elgin’s long-contested marbles would be taken very good care of indeed were they transferred to Athens.

Today, the Elgin marbles would be safe in either Britain or Greece. So, the issue now is who is most entitled to them.

Elgin claimed that he removed the marbles with the blessing of the Ottoman Empire, which ruled over Greece at the time. The veracity of his claim has been disputed, but however we parse the laws of a vanquished empire, even a fairly conducted legal and historical investigation into contemporary property rights is unlikely to resolve this because it is a matter of cultural identity.

Arguably, even if Elgin had permission from the Ottomans, that is beside the point. Why should a foreign occupier—that had the nerve to store gunpowder in the Parthenon, thus making it an obvious target for cannonballs—get to dole out what was left of the sculptures, having sacrificed some of them to wage war?

Arbitrating cultural identity is a wicked problem.

The Elgin marbles are obviously part of Greece’s cultural heritage. But contemporary Greek citizens are not the sole inheritors of ancient Athens. All of Western civilization famously emerged out of the bedrock of classical antiquity, in an era when ancient Greece was cross-fertilized by the ancient Near East (what we now call the Middle East), a flourishing of art and traditions that culminated when the Romans studied, imitated, and spread ancient Greek culture throughout their vast empire. Great Britain was once part of that empire and is crisscrossed with the ruins of ancient Roman roads and forts. The Elgin marbles, then, are part of Britain’s history, too.

To return to the King Solomon analogy: The Elgin marbles are like a child whose mother died long ago, who has been abused for many years by a foster care system in which a series of unscrupulous guardians have inflicted pain upon her. Now there are two prospective mothers vying to adopt the child, each claiming that she is a distant relative.

Kierstead writes:

The most important [philosophical argument for keeping the marbles in London] is the idea of the “encyclopaedic museum”—a repository of objects from different cultures and times, which tells a story that cuts across today’s national boundaries. This model is often contrasted with a more ethnocentric approach, in which all historical artefacts must be returned to the countries they came from—an approach that British critics say underlies Greece’s claims to the Elgin marbles.

Encyclopaedic museums should present humanity’s heritage as a gestalt—the complete cultural ecosystem that emerges out of our mind-boggling diversity and complexity. In what other context does the slogan “diversity is our strength” more readily apply than when we are engaged in the project of telling the overarching human story?

If encyclopaedic museums did not collect artefacts from all over the world, the only people who could see the most important of the objects that tell that story would be those with enough wealth and leisure time to travel extensively. As Kierstead points out:

the British Museum still offers cost-free entry to the general public, unlike the Acropolis Museum [where Greece would like to house the Elgin marbles], and currently welcomes three times as many visitors each year as its rival.

And the general public in London today is highly international, with residents and tourists as diverse as the British Museum’s collection. London is also home to a substantial Greek diaspora. In that city’s encyclopaedic museum, an immense range of people can experience the whole world’s story, including the part of that story told by the Elgin marbles.

Kierstead wonders how a more ethnocentric approach could be reasonably implemented:

This project would also throw up a host of problems, including in Greece. Do the treasures of the non-Greek Minoans belong in Athens or Crete, for example, and should the great altar of Pergamum, now in Berlin, be “given back” to Greece, or to Turkey, where the ruins of Pergamum are located?

History is messy. This poses logistical problems for the ethnocentric approach. But not so for the encyclopaedic museum, where presenting that mess can help show why the human story is so fascinating.

In this version of the Judgement of Solomon, the two alleged mothers are not just Britain and Greece, but two competing philosophies: the encyclopaedic versus the ethnocentric museum.

Kierstead emphasizes that property rights are a chief concern here and argues that the ethnocentric approach fails to differentiate between legitimate purchase and robbery:

any rapid slide towards returning cultural treasures to the geographical areas in which they were originally found might undermine an important difference between simple theft and the legitimate acquisition of antiquities and other artefacts.

There is an overwhelming case for the return of some artefacts, such as the Benin bronzes (essentially taken by conquest by British colonial forces). Another such case is that of the drawings belonging to Holocaust victim Arthur Feldmann, which the British Museum acquired from the Nazis and recently returned to his relatives after Parliament created an exception to the 1963 Act for artefacts obtained between 1933 and 1945.

But despite such cases, the great bulk of the objects in the world’s major museums (including the British Museum) have been acquired in legitimate ways.

But Kierstead’s defence of the encyclopaedic museum is even stronger than he may realize. Repatriating even the Benin bronzes poses knotty problems.

The writer David Frum travelled to Benin, in what is now southern Nigeria, in 2022. In “Who Benefits When Western Museums Return Looted Art?,” Frum describes the three-way local power struggle between the successful and beloved mayor of Benin; the oba (king) who was restored to his throne and who has little power, but is beloved by the people; and the famously corrupt Nigerian government. None of these three parties can guarantee that the Benin bronzes would not be looted were they returned to Nigeria.

As a result, Frum finds himself facing the same philosophical dilemma as Kierstead:

There are more fundamental questions to be pondered here, questions about whether history can be—or should be—unwound. Projecting the identities of the present upon the art of the past almost inevitably yields illusions, or worse.

Similarly, it is difficult to parse who is most entitled to claim that the Parthenon was foundational to their culture: contemporary Greeks or the West more broadly? And what about anyone and everyone who cherishes that historical era?

Like Kierstead, Frum wonders how the great altar of Pergamum could be repatriated when that ancient Greek ruin is currently located on Turkish national soil. Given the logistical nightmares such dilemmas present, as well as the perils of dealing with the corrupt Nigerian government, Frum argues:

A standard that art should belong to the present-day government of the place where that art was created centuries ago is not, to me, sustainable.

Frum concurs with Kierstead’s argument that encyclopaedic museums are a treasure because they serve the whole world:

Museums at centers of international commerce and travel connect rare artefacts to mass audiences. Before the coronavirus pandemic, the British Museum drew nearly 4 million visitors a year from outside the United Kingdom. Three-quarters of the Louvre’s nearly 10 million annual pre-COVID visitors came from countries other than France. The large and growing African diaspora in North America, too, should be able to see its heritage in museums in New York, Chicago, Washington, and Toronto.

We already ask encyclopaedic museums to fulfill a tremendous obligation. Telling the overarching story of humanity with nuance and care is a daunting task. As Frum concludes, we cannot also expect them to be our consciences:

Too many people look to art objects to do things that art cannot do: redress grievances, salve shame, absolve guilt.

Neither the encyclopaedic nor ethnocentric museum can resolve the pain our messy history has bequeathed to us. Whoever is the true mother of the Elgin marbles or the Benin bronzes, she will somehow hurt and disappoint her child—as all mothers, being merely human, are bound to do.

Mitsotakis was wrong to suggest that we would not find the Mona Lisa beautiful if the painting were torn in half. We cherish art fragments, like the Egyptian sphinx that lacks her nose, and Édouard Manet’s chopped-up painting “The Execution of Maximilian,” which his friend Edgar Degas tried to piece back together like a jigsaw puzzle (many fragments are still missing). And of course, millions of people are enthralled by the Parthenon in Athens, even if they have never seen the Elgin marbles in London—and vice versa.

I do not advocate cutting up famous paintings. But slashing the Mona Lisa is not an apt analogy for what happened to the Elgin marbles; neither is the Judgement of Solomon. Halving a baby is grotesque, whereas the Parthenon in its current state is sublime. Its beauty and historical significance endure in Athens, just as the Elgin marbles retain their grandeur in London. Perhaps it would be wonderful to reunite them, but it is wrong to suggest that they have lost their lustre.

Moreover, given that Elgin may have saved some marbles from total destruction, his actions were not obviously wrong. He was not operating in a world in which the Parthenon was a protected historical site.

Art history is replete with injustices. Frum offers a wise analysis of how we should deal with that brutal truth. He reminds us that the human past was a grim place for almost everybody, and few of those with the resources to command art in the first place were blameless—an indictment that certainly includes the rulers of Benin:

Ancient Benin produced cloth, pepper, and ivory—but not its own metal. The obas of Benin obtained the material for their glorious artworks by trading people they’d enslaved for brass sold by Portuguese merchants… Like the Roman Pantheon and Thomas Jefferson’s mansion at Monticello, the art of Benin flaunts the wealth gained by slavers. That history does not detract from the objects’ beauty. But it cannot be detached from the objects’ meaning.

…

The Western museum is a great accomplishment of human civilization. Museums may trace their origins to the crimes of kings and the arrogance of colonizers. In the here and now, they allow tens of millions of people to enjoy what were once the personal pleasures of a wealthy, powerful, titled few.

Kierstead’s choice of the term “encyclopaedic” is more fitting than Frum’s “Western,” because institutions like today’s British Museum, Louvre, and Met serve a highly international audience. But their ability to continue to reflect that internationalism in their collections has been called into question, as Kierstead points out:

One reason why it has been so difficult to arrive at a resolution in the case of the Elgin marbles is that they are now so high-profile that a decision to hand them to Greece would constitute a decisive blow against the encyclopaedic museum and in favour of the “repatriation” of the world’s cultural artefacts. If this happened, the writing would be on the wall for all the great global museums, from the British Museum to the Louvre (which also holds a few sculptures from the Parthenon). They wouldn’t stand empty anytime soon, but their prospects would not be promising.

The Elgin marbles are a bellwether of where the debate over “decolonizing” museums is headed. If they leave, other artefacts will surely follow—not only from the British Museum, but from the Louvre, the Met, and elsewhere.

Though the Earl of Elgin cut the Parthenon sculptures in half, the Elgin marbles helped make an encyclopaedic museum whole. The choice to undo that may cut another baby in two: a worldview in which every individual inherits the entire human story. If we forsake that idea, then our ugly history will continue to divide us.

Honouring an ancient art historical tradition, I drew a scene from the Judgement of Solomon (1 Kings 3:16–28). A fresco from Pompeii that probably portrays the allegory is generally considered the first known painting of a Biblical story. It was removed and relocated to the Museo Nazionale in Naples. Many artists have depicted the Judgement of Solomon, including Raphaël, Peter Paul Rubens, and William Blake.

It is complex. With the fall of Constantinople in 1204, the victorious Venetians pillaged and plundered the defeated city and the four horses were dismantled and shipped to their new resting place atop St. Mark's Basilica as a symbol of triumph. Are they going back to Turkey? What about the Temple of Dendur at the Metropolitan Museum? An ancient Egyptian temple built in the first century B.C. a gift from Egypt to the United States. Did the government have the right to give away a piece of the country's heritage? Did London have the right to sell London Bridge to the US. Then there's The Cloisters in New York, not to mention the huge number of historical objects stolen by Hearst. There's even talk about the Koh-i-noor diamond being repatriated but four different countries claim to be its rightful owner. And if repatriated who benefits ?

Amazing. Raises so many points to think about.

Thanks for this!