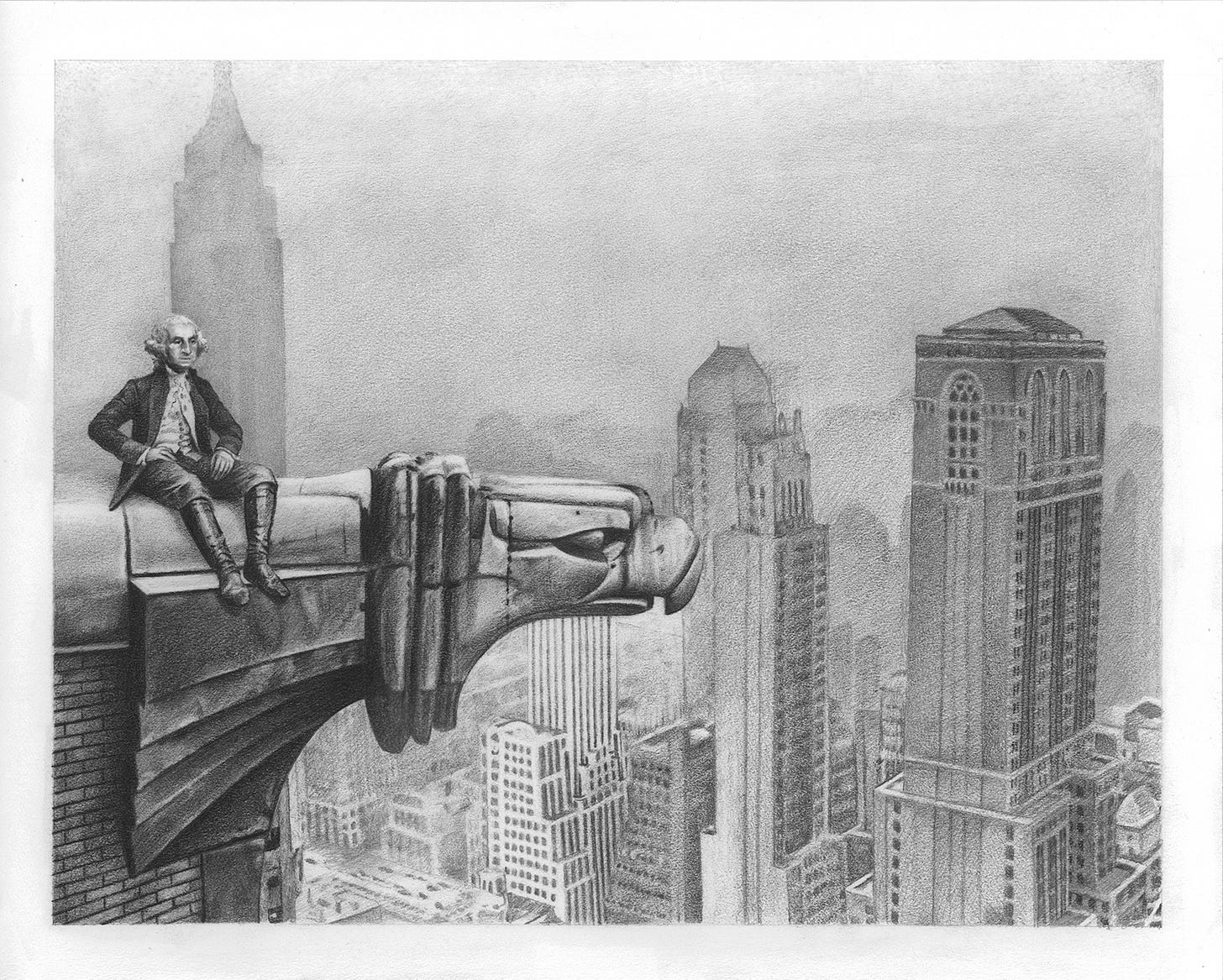

"America was supposed to be Art Deco."

When America abandoned beauty.

A couple months ago, the New York Times ran a piece titled, “The Chrysler Building, the Jewel of the Manhattan Skyline, Loses Its Luster.” Though its stainless steel eagles still glisten above Midtown Manhattan, Anna Kodé describes how inside of this skyscraper from 1930, crumbling ceilings are patched over with duct tape and water fountains spew something brown. Both people and rats have been getting stuck between floors in its richly decorated elevators since the ‘80s.

Reading about the decline of this architectural stunner, I recalled the Culture Critic declaring that “America was supposed to be Art Deco.” The pronouncement had startled me — that feeling when an epiphany grabs you by the shoulders, spins you around, and says, “Look.” In an essay about America's bulldozed architectural tradition, the Culture Critic elaborates:

It can be hard to imagine what an architecturally beautiful America would look like. Fortunately, the U.S. does have a history of design excellence to call its own: Art Deco.

In America’s earliest years, it relied heavily on classical architecture. Greek columns adorned many public buildings, while others used impressive stone and arches.

As America matured, though, it caught hold of a new design emerging in Paris. This lavish style added bold geometric decoration to everything from skyscrapers to jewelry, earning it the name arts décoratifs. The style caught on across the Atlantic, and Art Deco went on to define a good part of America’s 20th century.

Art Deco drew inspiration from the world of the classics: powerful vertical lines recall columns, and Greek figures frequently appear, like Prometheus dominating the Rockefeller Center. Yet it also incorporated elements of Modernism and historical French interior design, as well as influences from far-flung ancient Egypt, Persia, Mesoamerica and China.

In essence, it was Greek dominance remixed to the beats of the Jazz Age — the perfect expression of an ascendant American culture. Architecture for an age of optimism.

More than anything, Art Deco proved that America could take its core qualities — mass culture, technological progress, aggressive boldness, and luxury — and channel them into a genuinely beautiful style.

One of the most striking features of Art Deco skyscrapers is that so much ornamentation is at the very top. The patterned crescents and chrome eagles on the peak of the Chrysler Building are at eye-level only in the heavens, as if they were an offering to some ancient god. Photographers have the honor of bringing the details down to earth so that us mere mortals may marvel at them.

Throughout the decades, photos taken of Manhattan from atop the Chrysler Building document a stark shift in the American architectural tradition. Margaret Bourke-White — who would go on to become the first female war photojournalist, with unprecedented access to the Soviet Union and Stalin himself — was hired to photograph the construction of the Chrysler. She also made her studio in the new building, where she crept out onto its aerodynamic, steel gargoyles to take pictures of the canyons forming between the first skyscrapers in New York City. In her autobiography, she recalls:

On the sixty-first floor, the workmen started building some curious structures which overhung 42nd Street and Lexington Avenue below. When I learned these were to be gargoyles à la Notre Dame, but made of stainless steel as more suitable for the twentieth century, I decided that here would be my new studio. There was no place in the world that I would accept as a substitute.

Annie Leibovitz, famous for photos like the ones she took of John Lennon just hours before his murder, also stepped out onto a gleaming eagle in 1991. John Loengard's picture of Leibovitz carefully planting her feet on the gargoyle has perhaps become the more famous image, though. Bourke-White's biographer was there that day, and commented on Leibovitz's bravado, on the way she would let no one hold her steady, standing “free above the New York skyline with the wind whipping at her trousers.”

Between the time when Bourke-White documented the construction of the Chrysler Building and when Leibovitz followed in her footsteps 60 years later, the Art Deco skyscrapers that make New York City's skyline iconic were boxed in by plain, flat, ugly cubes. Known variably as the International Style, or Bauhaus influence, or glass box, or simply modern architecture, these are the ugly buildings that you stride past to visit the tourist traps, just before you sigh wistfully in front of some decorative monument, “They just don't make ‘em like they used to.”

This is what a century of glass boxes has reduced us to — relief at finding ourselves in Mordor rather than the Bauhaus.

Monstrosities like the Seagram Building, erected in 1958 by architect Ludwig Mies van der Rohe (often simply called Mies), were designed to vehemently reject all ornamentation. In 1976, the Times described that simple glass box as “one of New York's most copied buildings” that has “provided the inspiration for countless office towers around the world.” The Seagram Building was designed in the International Style, which London's Tate Gallery notes, “is seen as single-handedly transforming the skylines of every major city in the world with its simple cubic forms.”

Now about a century old, the glass box still thrives. A recent example is Brooklyn Tower, completed in 2022 by SHoP Architects, which at 1,066 feet high is the tallest in Brooklyn. Architectural Digest alleges that it is “neo-Art Deco,” whereas the New York Post bemoans that “It offers gloom with a view.” (Art Deco is decidedly not gloomy.) The Post quotes local discontents grumbling that the onyx-black skyscraper is “one more failure of imagination” with “evil vibes.” It has been nicknamed Sauron's Tower for its striking resemblance to that villain's lair.

But while some Brooklynites called it “a hideous blight,” the Post found at least one local man who saw the silver lining: “I’d rather it look evil than just be another boring rectangle in the skyline.” This is what a century of glass boxes has reduced us to — relief at finding ourselves in Mordor rather than the Bauhaus.

In his 1981 From Bauhaus to Our House, Tom Wolfe explains the architect's position:

The terms glass box and repetitious, first uttered as terms of opprobrium, became badges of honor. Mies had many American imitators… What did it matter if they said you were imitating Mies or Gropius or Corbu or any of the rest? It was like accusing a Christian of imitating Jesus Christ.

Thus the veritable carousel of glass boxes from New York to London to Tel Aviv to Tokyo. Wolfe notes how:

At Yale the students gradually began to notice that everything they designed, everything the faculty members designed, everything that the visiting critics (who gave critiques of student designs) designed… looked the same. Everyone designed the same . . . box . . . of glass and steel and concrete, with tiny beige bricks substituted occasionally. This became known as The Yale Box. Ironic drawings of The Yale Box began appearing on bulletin boards. “The Yale Box in the Mojave Desert" — and there would be a picture of The Yale Box out amid the sagebrush and the joshua trees northeast of Palmdale, California. “The Yale Box Visits Winnie the Pooh" — and there would be a picture of the glass-and-steel cube up in a tree, the child's treehouse of the future. “The Yale Box Searches for Captain Nemo" — and there would be a picture of The Yale Box twenty thousand leagues under the sea with a periscope on top and a propeller in back. There was something gloriously nutty about this business of The Yale Box! — but nothing changed. Even in serious moments, nobody could design anything but Yale Boxes.

Back in the ‘80s, long before the eye of Sauron menaced downtown Brooklyn, Wolfe complained that the Postmodernists were kidding themselves if they believed they had moved past all this monotony:

The term Post-Modernism caught on as the name for all developments since the general exhaustion of modernism itself . . . Post-Modernism was perhaps too comforting a term. It told you what you were leaving without committing you to any particular destination” and “tended to create the impression that modernism was over because it had been superseded by something new. In fact, the Post-Modernists . . . had never emerged from the spare little box fashioned in the 1920s by Gropius, Corbu, and the Dutchman. For the most part, they were busy doing nothing more than working changes on the same tight little concepts, now sixty years old, for the benefit of one another.

Now for a hundred years, Modernist architects have been stabbing the world's cities repeatedly with their glass shards. Meanwhile, America's last decorative architectural style, Art Deco, died young like James Dean — handsome, beloved, and snuffed out before his thirtieth birthday.

So they skinned their buildings like a fresh kill.

If America was supposed to be Art Deco, then what happened to that muscular aesthetic decked out with delicate details? It was the last ornamental architectural style before an infestation of austere cubes degraded the New York City skyline — and that of metropolises the world over. Wolfe offered the clearest interpretation of what happened when he remarked, “How much explaining did a tidal wave have to do?”

In the 20th century, architecture became cynical. The canonical story is that many prominent artists of all kinds — including architects, but also painters, composers, poets, and all the rest — claimed to be so horrified by the world wars that they decided traditional beauty was dishonest, or at the very least trite and pastiche. In the architectural permutation of this stance, pioneers of the International Style — like Walter Gropius, le Corbusier, and Ludwig Mies van der Rohe — remade architecture in the vision of their politics, which were characterized by disgust with all things bourgeois, namely ornamentation. So they skinned their buildings like a fresh kill. Mies was known for quipping that “Less is more . . . My architecture is almost nothing.”

War seemed more perverse in the 20th century, because modernity was beginning to alleviate the human condition at the same time that it was enabling slaughter at economies of scale. Inventors in the 1930s came up with comforts like the window AC unit as well as the gas chamber. Those prominent architects and artists who became disillusioned by this incongruity between technological and moral progress did not appreciate the distinction between tame and wicked problems. Tame problems are technical, scientific, testable — everyone can agree on the nature of the problem, so it can be solved like a puzzle; wicked problems are social, psychological, intractable — no one can agree on the root cause, so people just argue.

Art Deco celebrates our prowess at solving tame problems, as exemplified in the homage paid by the Chrysler Building to the newfound speed and independence born of the modern automobile.1 Meanwhile, Modernists wallowed in our impotence to resolve wicked ones. Wolfe writes that, “The rubble, the ruins of European civilization, was an essential part of the picture. The charred bone heap in the background was precisely what made an avant-gardist such as Breton or Picasso stand out so brilliantly.” No earlier generation had figured out how to fix its wicked problems either, but neither did our ancestors commit atrocities from the comfort of air conditioned rooms. A jaded reaction to modernity became the culturally ascendant attitude, when in response to the ugliness of war and genocide, Mies and his acolytes made the world even uglier.

Today these anti-beauty beliefs are imprinted on our cities as surely as Rome is marked by Catholicism. And the comparison is not merely superficial, given the Modernist architect's religious fervor for removing ornamentation. Wolfe describes them reenacting an historic scene of religious fanaticism:

With the somewhat grisly euphoria of Savonarola burning the wigs and fancy dresses of the Florentine fleshpots, deans of architecture went about instructing the janitors to throw out all plaster casts of classical details, pedagogical props that had been accumulated over a half century or more. I mean, my God, all those Esquiline vase-fountains and Temple of Vesta capitals . . . How very bourgeois.

At Yale, in the annual design competition, a jury always picked out one student as, in effect, best in show. But now the students rebelled. And why? Because it was written, in the scriptures, by Gropius himself: “The fundamental pedagogical mistake of the academy arose from its preoccupation with the idea of individual genius.” Gropius' and Mies' byword was “team” effort. Gropius' own firm in Cambridge was not called Walter Gropius & Associates, Inc., or anything close to it. It was called “The Architects Collaborative.” At Yale the students insisted on a group project, a collaborative design, to replace the obscene scramble for individual glory.

As Wolfe points out, this was all very un-American:

Here we come upon one of the ironies of American life in the twentieth century. After all this has been the American century, in the same way that the seventeenth might be regarded as the British century. This is the century in which America, the young giant, became the mightiest nation on earth, devising the means to obliterate the planet with a single device but also the means to escape to the stars and explore the rest of the universe.

…

In short, this has been America's period of full-blooded, go-to-hell, belly-rubbing wahoo-yahoo youthful rampage — and what architecture has she to show for it? An architecture whose tenets prohibit every manifestation of exuberance, power, empire, grandeur, or even high spirits and playfulness, as the height of bad taste.

The Art Deco Society of New York has published a number of essays attempting to define the style, which is in some dispute. Art Deco contains multitudes. And unlike the contemporaneous Modernists who disdained it, the short-lived movement had no need for manifestos.

In one such essay, David Garrard Lowe writes that the Chrysler Building is quintessential Art Deco, with “all of the accouterments” of the era:

The building embodies the style’s fascination with speed and movement, two signatures of the modern era. It is no accident that it is a tangible advertisement for the man who paid for it, Walter Chrysler. It is significant that the 31st floor setback is embellished with facsimiles of hood ornaments and radiator caps of the 1929 Chrysler. These Moderne gargoyles drive away all memories of past transportation — horses and buggies and chariots. The décor of the upper level suggests the spokes of automobile tires. Now, better lit than ever before, they appear to whirl in the night sky. The Nirosta steel needle pierces the clouds.

Most importantly, “the jewel of the Manhattan skyline" embodies Art Deco's “enthusiastic embrace of beauty":

The Chrysler Building’s lobby is a dazzling exemplification of the style’s unabashed romance with beauty. One enters through a colossal portal set in gleaming black granite, held aside like a parting stage curtain. In the lobby, the ceiling is a wonderful canopy with, at its center, a perspective view of the building itself. The doors of its elevators not only exemplify the style’s obsession with beauty, but also its quest to search the world for new inspiration. Here is the recent discovery of the tomb of Tutankhamen; the doors bear the image of the fans painted on a sumptuous box found in his tomb in 1922. Even the little stairway at the corner of the lobby, which leads to the second floor, exemplifies in the swirl of its metallic railing the charm of Art Deco design.

Like the jazz music that scored the rise of New York City's earliest skyscrapers — the style was often called Jazz Moderne in its own time, and only became known as Art Deco during its resurgent popularity in the ‘60s — Art Deco was a syncretism of many older traditions, reimagined during the dynamism of the early 20th century. While Modernist architects of the day were following Bauhaus orthodoxy of “starting from zero” by liberating buildings from ornamentation and historical influence, Art Deco upheld art traditions from across the world — Greek, Egyptian, Mayan, Japanese — and merged them with new, industrial materials and methods. It represents everything that architects of the International Style railed against, as Wolfe describes:

The country of the young Bauhäusler, Germany, had been crushed in the war and humiliated at Versailles; the economy had collapsed in a delirium of inflation; the Kaiser had departed; the Social Democrats had taken power in the name of socialism; mobs of young men ricocheted through the cities drinking beer and awaiting a Soviet-style revolution from the east, or some terrific brawls at the very least. Rubble, smoking ruins — starting from zero! If you were young, it was wonderful stuff. Starting from zero referred to nothing less than re-creating the world.

Whereas Art Deco motifs celebrate myriad art traditions, the Modernists lost much of their architectural heritage to the bombs and then claimed they had never liked it very much anyway. Opulent Art Deco flowered in America, which Wolfe called “the very Babylon of capitalism,” where tycoons of industry could afford to import luxuries like the monumental slabs of red Moroccan marble that form the walls of the Chrysler Building lobby. Art Deco does sometimes include murals by the Social Realists who dominated painting in the 1930s, but this was no socialist artform. Indeed, Nelson Rockefeller sacked Diego Rivera for trying to include a portrait of Vladimir Lenin in his fresco for another Art Deco icon, Rockefeller Center.

But even some who like Art Deco are put off by its embarrassment of riches. In another Art Deco Society essay, Jared Goss, a former curator of modern and contemporary art for the Metropolitan Museum of Art, claims that:

But perhaps the most important aspect of Art Deco was its unabashed commercialism: it was specifically conceived to appeal to consumers, whether rich or middle class (and it is just this which separates it from Modernism, the contemporaneous movement which was shaped instead by high-minded polemics and ideology rather than commerce).

The most important aspect? This is ahistorical. Art Deco appealed to John D. Rockefeller, Jr. as the Renaissance appealed to Lorenzo de’Medici. For all of human history, wealthy and powerful men have commissioned architects to build monuments to their god, their empire, and their own splendor; for all of human history, men of modest means have admired their creations. That all kinds of people covet exquisite ornamentation is quite ordinary.

What really separates Art Deco from the International Style — rather, what separates all of architectural history from those unadorned, flat, glass boxes — is beauty. The Chrysler Building is of a kind with luxurious palaces like Versailles. Architectural expressions of beauty have evolved over millennia, recombining tradition and accumulating new innovations. When he designed the Chrysler Building, William Van Alen took advantage of new techniques and materials to erect the world's tallest skyscraper (until Empire State overtook it a year later), just as Filippo Brunelleschi figured out how to engineer the largest ever cathedral dome in Florence until it was overtaken by St. Peter's Basilica in Rome.

Historically, every subsequent artistic style has invented a novel aesthetic by innovating on tradition, as the hip-hop artist samples a beat. These inventive interpretations of what came before are the norm. Art Deco is special in how its architects gathered together such a variety of disparate cultural traditions, and merged them with a celebration of early 20th century progress — but it followed the same historical formula of honoring the past with a twist.

Samuel Hughes, an Oxford research fellow who studies architecture and urbanism, explains that this austere turn was unprecedented in “The Beauty of Concrete”:

One of the unifying features of architectural styles before the twentieth century is the presence of ornament. We speak of architectural elements as ornamental inasmuch as they are shaped by aesthetic considerations rather than structural or functional ones. Pilasters, column capitals, sculptural reliefs, finials, brickwork patterns, and window tracery are straightforward examples. Other elements like columns, cornices, brackets, and pinnacles often do have practical functions, but their form is so heavily determined by aesthetic considerations that it generally makes sense to count them as ornament too.

Ornament is amazingly pervasive across time and space. To the best of my knowledge, every premodern architectural culture normally applied ornament to high-status structures like temples, palaces, and public buildings. Although vernacular buildings like barns and cottages were sometimes unornamented, what is striking is how far down the prestige spectrum ornament reached: our ancestors ornamented bridges, power stations, factories, warehouses, sewage works, fortresses, and office blocks. From Chichen Itza to Bradford, from Kyiv to Lalibela, from Toronto to Tiruvannamalai, ornament was everywhere.

Since the Second World War, this has changed profoundly. For the first time in history, many high-status buildings have little or no ornament. Although a trained eye will recognize more ornamental features in modern architecture than laypeople do, as a broad generalization it is obviously true that we ornament major buildings far less than most architectural cultures did historically. This has been celebrated by some and lamented by others. But it is inarguable that it has greatly changed the face of all modern settlements. To the extent that we care about how our towns and cities look, it is of enormous importance.

Hughes goes on to debunk the popular economic explanation to the question, “Why are buildings today simple and austere, while buildings of the past were ornate and elaborately ornamented?”:

Ornament, it is said, is labor-intensive: it is made up of small, fiddly things that require far more bespoke attention than other architectural elements do. Until the nineteenth century, this was not a problem, because labor was cheap. But in the twentieth century, technology transformed this situation. Technology did not make us worse at, say, hand-carving stone ornament, but it made us much better at other things, including virtually all kinds of manufacturing and many kinds of services. So the opportunity cost of hand-carving ornament rose. This effect was famously described by the economist William J Baumol in the 1960s, and in economics it is known as Baumol’s cost disease.

To put this another way: since the labor of stone carvers was now far more productive if it was redirected to other activities, stone carvers could get higher wages by switching to other occupations, and could only be retained as stone carvers by raising their wages so much that stone carving became prohibitively expensive for most buyers. So although we didn’t get worse at stone carving, that wasn’t enough: we had to get better at it if it was to survive against stiffer competition from other productive activities. And so the labor-intensive ornament-rich styles faded away, to be replaced by sparser modern styles that could easily be produced with the help of modern technology. Styles suited to the age of handicrafts were superseded by the styles suited to the age of the machine. So, at least, goes the story.

This is what economists might call a supply-side explanation: it says that desire for ornament may have remained constant, but that output fell anyway because it became costlier to supply. One of the attractive features of the supply-side explanation is that it makes the stylistic transformation of the twentieth century seem much less mysterious. We do not have to claim that — somehow, astonishingly — a young Swiss trained as a clockmaker and a small group of radical German artists managed to convince every government and every corporation on Earth to adopt a radically novel and often unpopular architectural style through sheer force of ideas. In fact, the theory goes, cultural change was downstream of fairly obvious technical and economic forces. Something more or less like modern architecture was the inevitable result of the development of modern technology.

But contrary to the hope that we didn't really disown beauty, Hughes goes on to show just how affordable ornamentation has become. It is intuitive to assume that some ornamentation must surely cost more than none at all, but the most salient factor is that:

It is just not true that twentieth-century technology made ornament more expensive: in fact, new methods of production made many kinds of ornament much cheaper than they had ever been. Absent changes in demand, technology would have changed the dominant methods and materials for producing ornament, and it would have had some effect on ornament’s design. But it would not have resulted in an overall decline. In fact, it would almost certainly have continued the nineteenth-century tendency toward the democratization of ornament, as it became affordable to a progressively wider market. Like furniture, clothes, pictures, shoes, holidays, carpets, and exotic fruit, ornament would have become abundantly available to ordinary people for the first time in history.

Hughes goes into detail about the history of architectural efficiency. He explains the evolution of carving and casting techniques. There were both premodern and modern methods for mass producing architectural ornaments, but modern technology was vastly more productive, and Art Deco was a major beneficiary of this streamlining:

A less important but still significant factor was the emergence of extremely large individual buildings. Most early twentieth-century skyscrapers actually had a complete set of ornament modeled for them bespoke, but the buildings were so enormous that substantial economies of scale were still achieved. This is one reason why terracotta was such a popular material for skyscrapers in interwar America, a component of American Art Deco that has now become a striking part of its visual identity.

Art Deco is to the International Style as jazz is to 4′33″ by John Cage, who composed four minutes and thirty-three seconds of silence so that concert goers could listen to their shuffling feet and barely suppressed coughs in lieu of a traditional symphony.

After breaking down how modern technology made ornamentation more affordable than it had ever been before — like trains suddenly making it possible to haul massive amounts of building materials for great distances — Hughes then points out that we can also just believe our lying eyes. The answer to whether or not architectural ornamentation died out due to budget cuts “should be obvious to anyone walking the streets of an old European city":

The vernacular architecture of the seventeenth or eighteenth century tends to be simple, with complex ornament restricted to the homes of the rich and to public buildings. In the nineteenth-century districts, ornament proliferates: even the tenement blocks of the poor have richly decorated stucco facades.

The revealed evidence is in fact overwhelming that the net effect between, say, 1830 and 1914 was mainly one of greater affordability. To be sure, the ornament of the middle and working classes was of stucco, terracotta, or wood, not stone, and it was cast or milled in stock patterns, not bespoke. These features occasioned much censoriousness and snobbery at the time. But we might also see them as bearing witness to the democratizing power of technology, which brought within reach of the people of Europe forms of beauty that had previously belonged only to those who ruled over them.

And then the Modernists came and took it all away again. The International Style stands against humanity's longstanding love of beauty as an aberration and an abomination. Art Deco is to the International Style as jazz is to 4′33″ by John Cage, who composed four minutes and thirty-three seconds of silence so that concert goers could listen to their shuffling feet and barely suppressed coughs in lieu of a traditional symphony. It is objectively more profound to hear Billie Holiday sing of summertime. When Modernists stripped our cityscapes of ornamentation, they claimed to be after what's real — but they confused being honest with being literal.

Ironically, only the dreaded bourgeois took them seriously:

The supply-side theory says that ornament declined because it became prohibitively expensive, which suggests that it would vanish from budget housing first and gradually fade from elite building types later. In fact, budget housing is almost the only place we find it clinging on.

The obvious explanation is that ornament survives in the mass-market housebuilder market because the people buying new-build homes at this price point are less likely to be influenced by elite fashions than are the committees that commission government buildings or corporate headquarters. The explanation, in other words, is a matter of what people demand, not of what the industry is capable of supplying: ornament survives in the housing of the less affluent because they still want it.

Wolfe made the same diagnosis:

It was not that craftsmanship was dying. Rather, the International Style was finishing off the demand for it, particularly in commercial construction. By the same token, to those who complained that International Style buildings were cramped, had flimsy walls inside as well as out, and, in general, looked cheap, the knowing response was: “These days it's too expensive to build in any other style.” But it was not too expensive, merely more expensive. The critical point was what people would or would not put up with aesthetically. It was possible to build in styles even cheaper than the International Style. For example, England began to experiment with schools and public housing constructed like airplane hangars, out of corrugated metal tethered by guy wires. Their architects also said: “These days it's too expensive to build in any other style.”

Modernist architects tamed men who might have become the next Walter Chrysler. He had proudly declared his intention to build a monument to himself, as was custom:

The day of the monarch such as Ludwig II of Bavaria, or the business autocrat such as Herbert F. Johnson of Johnson Wax, who personally selected architects for great public buildings was over. Governments and corporations now turned to the selection committee… And the mightiest of the mighty learned to take it like a man.

Hughes maintains that the standard story of “ancient crafts gradually dying out as they became economically obsolete” is a popular misconception:

I have told a different story. In the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the production of ornament was revolutionized by technological innovation, and the quantity of labor required to produce ornament declined precipitously. Ornament became much more affordable and its use spread across society. An immense and sophisticated industry developed to manufacture, distribute, and install ornament. The great new cities of the nineteenth century were adorned with it. More ornament was produced than ever before.

We can imagine an alternative history in which demand for ornament remained constant across the twentieth century. Ornament would not have remained unchanged in these conditions. Natural stone would probably have continued to decline, although a revival might be underway as robot carving improved. Initially, natural stone would have been replaced by wood, glass, plaster, terracotta, and cast stone. As the century drew on, new materials like fiberglass and precast concrete might also have become important. Stock patterns would be ubiquitous for speculative housing and generic office buildings, but a good deal of bespoke work would still be done for high-end and public buildings. New suburban housing might not look all that different from how it looks today, but city centers would be unrecognizably altered, fantastically decorative places in which the ancient will to ornament was allied to unprecedented technical power.

This was not how it turned out. In the first half of the twentieth century, Western artistic culture was transformed by a complex family of movements that we call modernism… Between the 1920s and the 1950s, modernist approaches to architecture were adopted for virtually all public buildings and many private ones. Most architectural modernists mistrusted ornament and largely excluded it from their designs. The immense and sophisticated industries that had served the architectural aspirations of the nineteenth century withered in full flower… it is a story of cultural choice, not of technological destiny. It was within our collective power to choose differently. It still is.

That we chose ugliness is so incomprehensible to some people that they believe a conspiracy theory called Tartaria about why decorative architecture like Art Deco ended: that a century ago, a cataclysmic event — the knowledge of which is suppressed by the elites — wiped out humanity's technical knowhow and ability to create beauty. Tartaria is as preposterous as it is sympathetic. Renouncing beauty just seems so bafflingly inhuman. “And why?” Wolfe asks, “They can't tell you. They look up at the barefaced buildings they have bought, those great hulking structures they hate so thoroughly, and they can't figure it out themselves. It makes their heads hurt.”:

I find the relation of the architect to the client in America today wonderfully eccentric, bordering on the perverse. In the past, those who commissioned and paid for palazzi, cathedrals, opera houses, libraries, universities, museums, ministries, pillared terraces, and winged villas didn't hesitate to turn them into visions of their own glory. Napoleon wanted to turn Paris into Rome under the Caesars, only with louder music and more marble. And it was done. His architects gave him the Arc de Triomphe and the Madeleine. His nephew Napoleon III wanted to turn Paris into Rome with Versailles piled on top, and it was done. His architects gave him the Paris Opéra, an addition to the Louvre, and miles of new boulevards. Palmerston once threw out the results of a design competition for a new British Foreign Office building and told the leading Gothic Revival architect of the day, Gilbert Scott, to do it in the Classical style. And Scott did it, because Palmerston said do it.

In New York, Alice Gwynne Vanderbilt told George Browne Post to design her a French château at Fifth Avenue and Fifty-seventh Street, and he copied the Château de Blois for her down to the chasework on the brass lock rods on the casement windows. Not to be outdone, Alva Vanderbilt hired the most famous American architect of the day, Richard Morris Hunt, to design her a replica of the Petit Trianon as a summer house in Newport, and he did it, with relish. He was quite ready to satisfy that or any other fantasy of the Vanderbilts. “If they want a house with a chimney on the bottom,” he said, “I'll give them one.” But after 1945 our plutocrats, bureaucrats, board chairmen, CEO's, commissioners, and college presidents undergo an inexplicable change. They become diffident and reticent. All at once they are willing to accept that glass of ice water in the face, that bracing slap across the mouth, that reprimand for the fat on one's bourgeois soul, known as modern architecture.

Sometimes even the Modernist clerics of the highest order — even Ludwig Mies van der Rohe himself — couldn't take it like a man. Even Mies relapsed and resorted to ornamentation. Wolfe calls the Seagram Building on Park Avenue “the single greatest monument" to the International Style, and he reveals that it houses a dirty secret:

Exposing the metal had presented a problem. Mies' vision of ultimate nonbourgeois purity was a building composed of nothing but steel beams and glass, with concrete slabs creating the ceilings and floors. But now that he was in the United States, he ran into American building and fire codes. Steel was terrific for tall buildings because it could withstand great lateral stresses as well as support great weights. Its weakness was that the heat of a fire could cause steel to buckle. American codes required that structural steel members be encased in concrete or some other fireproof material. That slowed Mies up for only a little while. He had already worked it out in Chicago, in his Lake Shore apartment buildings. What you did was enclose the steel members in concrete, as required, and then reveal them, express them, by sticking vertical wide-flange beams on the outside of the concrete, as if to say: “Look! Here's what's inside.” But sticking things on the outside of buildings. . . Wasn't that exactly what was known, in another era, as applied decoration? Was there any way you could call such a thing functional? No problem. At the heart of functional, as everyone knew, was not function but the spiritual quality known as nonbourgeois. And what could be more nonbourgeois than an unadorned wide-flange beam, straight out of the mitts of a construction worker?

Ornamental architecture is like an old growth forest.

Elsewhere, Modernists were so obsessed with flat roofs — pitched roofs were bourgeois — that their buildings buckled under heavy snow. They fell short of their dream of flaying buildings down to their skeletons to deprive each one of ornamentation, because some features they considered superfluous were in fact necessary. At least their nonbourgeois, faux-functional, wide-flange beams were ugly — and wasn’t that the real mission?

Unlike the Modernist buildings that always seem in need of a pressure wash, which sooner or later become fixtures of urban blight, ornamental architecture benefits from the patina of time. The American poet John Greenleaf Whittier captured this effect when he declared, “O Beauty, old yet ever new!” Age generates mystery, allusions to untold and forgotten stories from generations past. Or in the extreme, entropy and tragedy transform beautiful architecture into romantic ruins like Heidelberg Castle. Ornamental architecture is like an old growth forest.

I visited the Chrysler Building last week with a heavy heart, worried that I would find it in disrepair. But the lobby appeared to be in good order, and I could only see one blemish. It was unobtrusive. When I asked the doormen if they had rushed to fix up the place in reaction to the Times piece from a couple months back, they glowered and told me that the article was a slanderous misrepresentation. These men clearly adored their Art Deco masterpiece, and they felt personally affronted.

The Chrysler Building has not lost its luster. It may be true that the offices above the lobby are in shambles and the water is brown — who to believe? — but without permission to ride those intricately ornamented elevators upstairs, I was left agape in the marbled lobby. Upon leaving and then looking back from a few blocks away, the Chrysler eagles, bright as ever, still blinded me as they caught the sun — O Beauty, old yet ever new!

I’m on record as hating cars, but I can’t help it — the Chrysler Building is my favorite skyscraper:

This essay is paradigmatic of what draws me to Substack. Having no special interest in architecture, it's a delight to be snared into contemplation: Why have I always been partial to Art Deco and find myself returning to its best manifestations in cities such as Barcelona or Paris? Come to think of it, I have been victimized by the brutalism of Bauhaus architecture at several college campuses, literally in one case, where the flat-roof library was infamous for dropping clods of ceiling on study carrels and their unsuspecting students.

Now, I am armed with theories to explain Art Deco's untimely demise, from cultural to economic supply-side to the conspiratorial (I'm keyed in to a lot of conspiracy theories but the Tartaria conspiracy ain't one of them).

So many wordsmith edibles here, it would be hard to choose just one. When you note the trickiness to defining Art Deco because it "contains multitudes," I immediately recalled the very American poetry of Walt Whitman:

"Do I contradict myself?

Very well then I contradict myself,

(I am large, I contain multitudes)."

Come to think of it, Uncle Walt might just have been the poetic avatar of the Art Deco style, roughly 3/4 of a century before its too-brief, butterfly existence!

And yes, it is "objectively more profound to hear Billie Holiday sing of summertime."

“after 1945 our plutocrats, bureaucrats, board chairmen, CEO's, commissioners, and college presidents undergo an inexplicable change. They become diffident and reticent.”

This is Burnham’s Managerial Revolution. BTW they just gave up, it’s “democracy” - which means committees. It has now trust me infected most government and corporate workers. That’s if one is even still working…

The GOOD NEWS is when someone gives up … they also get out of the way. Time for Beauty- even if it takes the Beast.